Tanzania’s enemies of the state: pregnant young women

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In May, when Sarah (not her real name) was about 15 weeks pregnant, she dropped out of state secondary school in the Shinyanga region of northern Tanzania. “It was difficult to continue because of my appearance,” explains the diminutive 17-year-old, who is due to give birth any day. “The environment was really uncomfortable. There was no support.”

Exacerbating the situation were the circumstances in which she became pregnant. “I was raped by my brother-in-law, but my sister said, ‘You’re lying — my husband would never rape anyone’,” Sarah explains. “I was beaten at my house. I was not provided with food. They were ashamed I was pregnant.”

She is one of 100 teenage girls studying at the Agape Knowledge Open School in Chibe, a village, 10km north of Shinyanga town. All the girls there have been abused, had babies, been rescued from child marriage, or experienced a combination of all three.

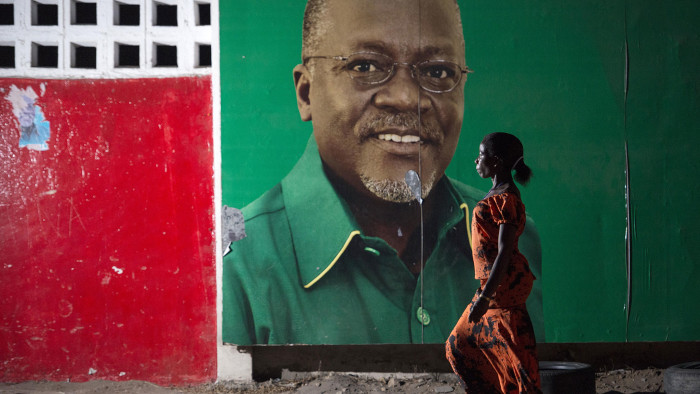

Even had Sarah wanted to remain at her state school, she would only have been able to continue for another month. In June, John Magufuli, Tanzania’s president, announced that no pregnant girl would be allowed to study in a state school, nor readmitted after giving birth.

“As long as I am president no pregnant student will be allowed to return to school,” he said, reacting to a debate in parliament. “We cannot allow this immoral behaviour to permeate our primary and secondary schools. After getting pregnant, you are done.”

The president’s intervention reversed the slow but steady progress in girls’ rights made under his predecessor, Jakaya Kikwete. It also highlighted the scale not only of teen pregnancies in Tanzania, but the broader issues of child marriage and girls’ rights.

There were 69,000 teen pregnancies in Tanzania last year, according to government data. About 21 per cent of girls aged 15-19 have given birth, with the figure rising to 45 per cent in some areas of the country. The child marriage rate is more than 35 per cent nationally, and is at its highest, at 59 per cent, in Shinyanga. Some 20 per cent of Tanzanian girls also suffer female genital mutilation (though activists believe the true figure is higher; it reaches 81 per cent in one region, Manyara). All these figures are lower than they were five years ago, but activists fear the president’s hardline stance will reverse the gains that have been made.

Magufuli has not explained why he is reversing Kikwete’s policies: local activists ascribe it to a combination of factors. “It’s the way he was raised, the issue and the nation’s patriarchal culture combined with power,” says the head of one organisation working in the field, who was too afraid to speak on the record.

Magufuli justified his view by saying that pregnant girls would set a bad example to their peers and that new mothers would be disruptive. “After calculating a few maths sums she’d be asking the teacher in the classroom, ‘Let me go out and breastfeed my crying baby’,” he said.

The reaction from girls’ rights advocates, both domestically and internationally, was swift and emphatic. Naitore Nyamu-Mathenge, of Equality Now, a Kenya-based rights group, says Magufuli’s approach is discriminatory. “You’re targeting one person; you’re not targeting the root cause of this problem,” she says. “For a minor who cannot even consent to sexual relations, the government should look at it as victimisation.”

The president has refused to compromise and Mwigulu Nchemba, the home affairs minister, has threatened to deregister non-governmental organisations that campaign for teenage mothers to be allowed back into school.Headteacherss who failed to comply with the orders would be fired, he said. “If we want to keep our jobs, we have no choice,” says one headteacher of a state school in Dar es Salaam, the country’s commercial capital. “There is no room for debate on anything when the president has spoken.”

When Halima Mdee, an opposition member of parliament, attacked the president’s position, the reaction was fierce. The state charged her with insulting the president. “I was telling him he’s not above the law,” she explains. “We have the constitution, we have laws that provide opportunities here. There are certain conventions and treaties that protect people who are pregnant. Some people might make decisions they regret when they grow up and shouldn’t be punished for them.” Mdee is due to appear in court for a preliminary hearing.

The fear of retribution is now so pervasive that many Tanzania-based organisations refused to comment on the record about the issue, as did one of the world’s largest NGOs working in this field. “It’s just too sensitive,” a spokesperson says.

Magufuli was also supported by the Catholic Church in Tanzania. According to local media reports, Damian Dallu, the archbishop of Songea, said in a sermon in July that allowing pregnant girls to study was “not part of African culture”. “It’s a foreign idea that wants us to defy our culture,” he is reported to have said. “What kind of schools will we have if we allow students to be mothers?”

Activists retort that it is unfair to hold the vast majority of the girls who become pregnant responsible for their actions. “There are so many cross-cutting issues,” says Valerie Msoka, who works with the Tanzania Ending Child Marriage Network, a coalition of 35 organisations working together to end child marriage in the country. “There’s culture, there’s religion, there’s the socio-political aspect, the contradictory laws that are in place and the lack of political will to take the issue seriously enough.”

Tanzania’s myriad conflicting laws are a case in point. The Sexual Offences Special Provisions Act of 1998 guarantees equality for women and in early 2016 the Education Act was amended to state it would be unlawful to marry a primary or secondary school pupil.

In 2016, the high court ruled that sections of the 1971 Marriage Act, which allow girls to marry at 15 with parental consent and at 14 with a court order, were unconstitutional. The court gave the government a year to make the changes, but this has yet to happen. Laws governing abortion are equally unclear, which means that most women will not risk seeking a termination.

The country has ratified the 2007 African Charter’s Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa, which allows abortion in cases of rape, incest or if the life of either the mother or child is threatened. But this too has yet to be incorporated into national law.

Poverty is a major contributing factor to both child marriage and pregnancy. While state education is officially free, there are often hidden fees in addition to uniforms and books. Many girls live up to 15km away from their secondary school and so take a boda boda (a motorcycle taxi) to save a gruelling walk.

“So many girls have told me, ‘The boda boda rider asks me to pay and I pay with my body’,” Msoka says. Similar stories abound concerning shopkeepers, she says.

Another 17-year-old pupil at the Agape school says she is there because her family is poor. “My relatives forced me to get married for a dowry price of four cows,” she says. “My mother didn’t support [the decision], but she had no choice. My husband was 31 and I was 12. He forced me to stay at home and I had a baby the following year.”

She was rescued shortly after giving birth and her daughter, now three years old, lives with her mother. “I want to go to university to be a lawyer to fight for girls’ rights,” she says with steely determination. “The president should realise we don’t get pregnant by choice,” she says. “I’d like to advise him to think of us and change his mind.”

If she ever gets to deliver her advice to Magufuli she would be a rarity. In the almost two years since he became president, the former public works minister — who is known as “The Bulldozer” for his uncompromising attitude — has become increasingly authoritarian as he seeks to eliminate the nation’s endemic corruption and legendary bureaucratic inefficiency. “Tanzania has become a dictatorship,” says Mdee. “When he came to power, many people saw him as this guy who wants to fight corruption and do good. But now they’re seeing the other side of him.”

Last month, however, the government appeared to qualify its position and said pregnant girls would be allowed to pursue vocational training instead of school. “We don’t intend to exclude teenage mothers in their quest for education,” Hamisi Kigwangalla, the deputy minister for health and children, told a conference. “They will instead be accommodated through an alternative channel instead of the mainstream education system.” It is not clear, however, who will qualify for this option or how their participation will be financed.

Activists say that little is likely to change under this president. “People take his statements as law,” says Felista Mauya of the Legal and Human Rights Centre in Dar es Salaam. “If we have a president who doesn’t see that teen pregnancy needs to be tackled properly, then where are we heading?”

Comments