Adidas’ new superstar

Simply sign up to the Fashion myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

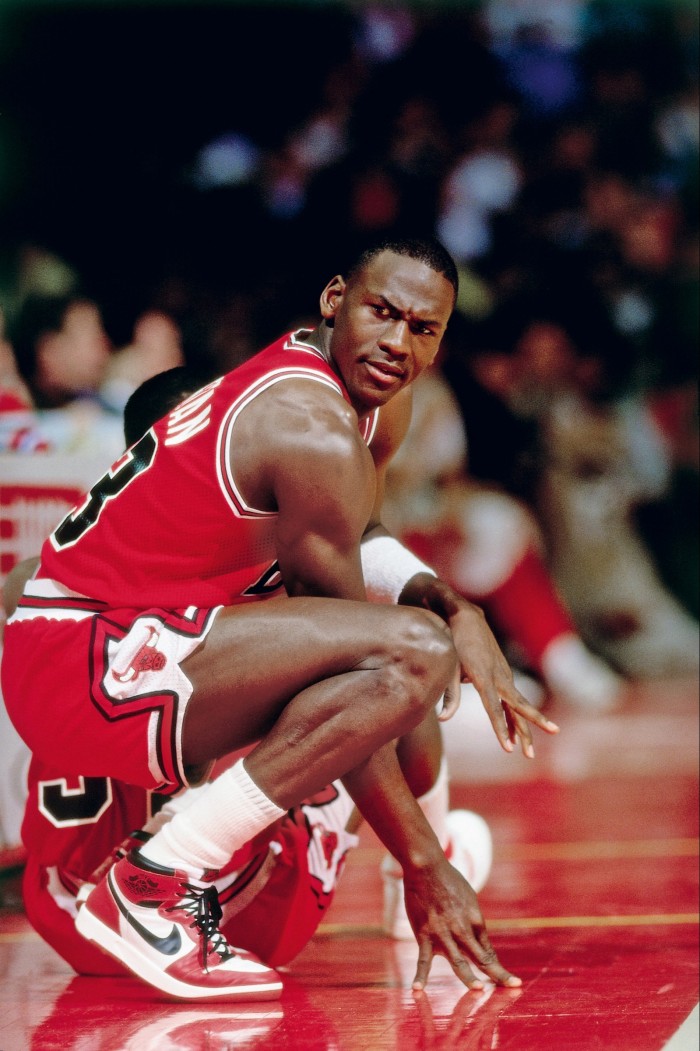

There’s an episode in The Last Dance, the Netflix series that has evoked widespread nostalgia for Michael Jordan’s golden years, in which the basketballer is lacing up his shoes – a pair of Nike Air Jordans, naturally. The red, white and black hi-tops are the same sneakers he wore to play at Madison Square Garden some 13 years earlier, and he’s giving them a final, ceremonial run in his last game on the court with the Chicago Bulls. At the time, Jordan said: “It’s kind of fun to come back here and play and… think about some of the games I’ve had here. And the shoes are a part of that.” Indeed, Jordan’s signature sneakers played no small part in transforming the talented basketballer into a universally adored household name.

Jordan, of course, wasn’t the first or last star to be immortalised in a shoe. Chuck Taylor, Jack Purcell, Stan Smith and Walt “Clyde” Frazier were all sportsmen who had sneakers named after or created for them. This has been the avenue through which footwear brands have made their fortunes – put a celebrity’s name or face on a shoe and watch it fly off the shelves. Nike made $126m from Air Jordans in the first year. To date, Adidas has sold more than 100m pairs of Stan Smiths; they are arguably more famous than the tennis player after whom they’re named.

But it’s no longer only celebrities and sports stars putting their names to sneakers. The internet has upended consumer habits and transformed our concept of who might be considered influential. Bernard Koomson is a 30-year-old sneakerhead who has gone from Adidas intern to DJ to shoe designer in a decade. It’s a career trajectory fitting of his millennial age bracket.

Koomson is part of the A-ZX project that has seen him and 25 of Adidas’s biggest global partners reinterpreting the ZX model, one of the brand’s most popular styles. It first ran in 2008, featuring collaborations with the likes of now-defunct Paris retailer Colette and New York boutique Dave’s Quality Meats; 2020’s iteration features collaborations with some of the biggest names in streetwear and sneaker design. “From when I was 15, I told people, ‘I’m going to go to work for Adidas,’” says Koomson, who speaks with the conviction of someone determined to control their own narrative. “I was really trying to put it out there, that that was going to happen. It was my dream.”

Koomson grew up on an estate in a “middle of nowhere” town in Essex called Purfleet. As a kid, he was consumed by sneaker culture – the kind highlighted in ’90s hip-hop videos and Spike Lee films. “I could never afford sneakers,” he says. “I spent a lot of time outside the stores, not being able to buy [them]… so I was always thinking about creative ways I could get trainers.” He recalls selling some of his school meals and saving the money to buy shoes. “For breakfast, you could get a bacon sandwich or a sausage sandwich, and I would sell this for, like, £1 to a kid whose parents gave them dinner money,” he says. “I just wanted them and I didn’t want to press my mum.”

Koomson went on to study economics at the University of Essex. At weekends, he would travel into London’s Covent Garden, where he worked at Offspring, part of the high-street chain Office that specialises in sneakers. In 2011, he launched deadHYPE, a Facebook page where he wrote about, and sold, shoes. He identified the market long before sneaker resale became a billion-dollar business (a pair of Jordans sold for a record $560,000 last month). “I was selling trainers that were kind of hyped but, like, dead stock. So you couldn’t really find them anywhere,” says Koomson. They were rare shoes that he personally liked and thought other people might want – styles such as the Adidas X Jeremy Scott Bones, a hi-top with little plastic bones covering the laces, made famous by ASAP Rocky in his 2011 music video for Peso. “It sounds so normal now, but in 2011 it was not a big thing. It was a community where we’d just share and buy and sell with each other.”

While still working at Offspring, Koomson struck up a conversation with someone who worked at Adidas. So impressed were they by his knowledge of the brand, he landed an internship at the headquarters in Herzogenaurach, Germany. “I got to meet some of my favourite people – Kanye West, the guys that made the ZX trainer. Or like Stan Smith – I would never even imagine that I could be in the same room with him. Because I’m from an estate.”

In the years that ensued, Koomson moved to Amsterdam, started working full-time for Adidas, began DJing and founded a radio show before moving to Berlin and working as a festival programmer. He now runs deadHYPE as a consultancy, working with companies such as Universal Music, Spotify and Adidas on projects that tap into the same youth culture he’s become an expert on. Which is how he wound up designing a trainer alongside some of the biggest names in the world. “I wanted to make a sneaker that was like from when I was young,” he explains. “It goes back to estate logic. People just wanted a sneaker that didn’t get holes in it. A leather shoe that lasts for a long time and doesn’t get beat up.”

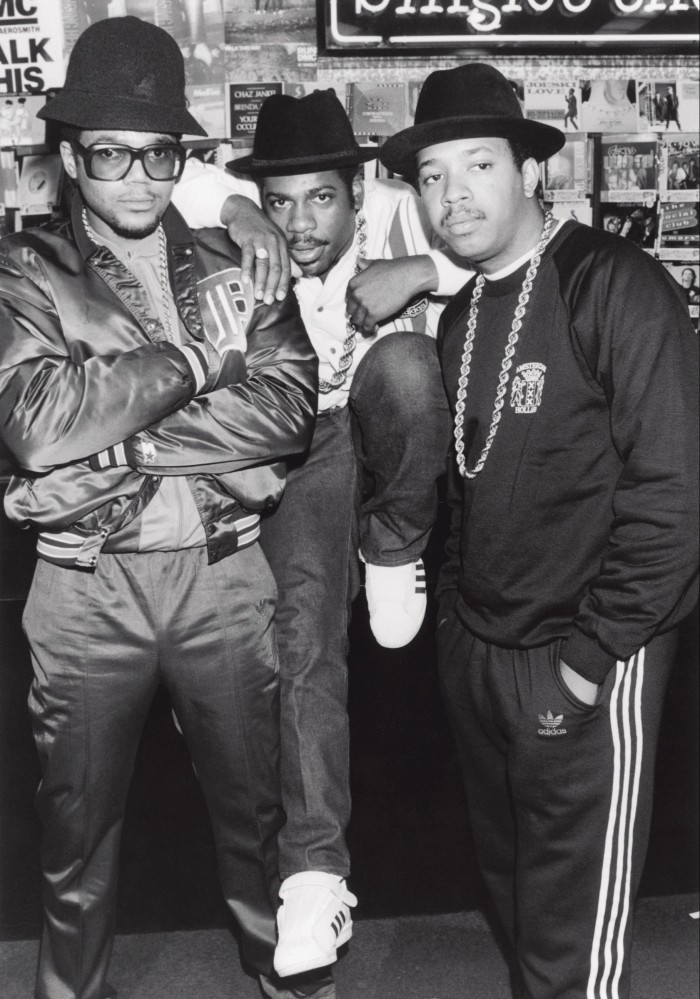

Koomson isn’t the first non-celebrity to front a sneaker with a big brand, although it’s a territory that’s mostly uncharted. “There are a few instances where we’ve seen micro-influencers or people who are cool being championed by the big brands, to engage in a more organic fashion,” says Kish Kash, a shoe collector, DJ and co-host of sneaker podcast Soleful. He points to brands Diadora and Ellesse as being particularly adept in this area. “Back in the day, the only people that would have collaborated on a sports shoe were Run DMC. Or you’d have people going to design school and finding their way into certain companies, like Tinker Hatfield or Steven Smith. Now, if you’re a creative and you’ve got great energy, brands are valuing that. The traditional barriers are being removed.”

Koomson believes the change is about brands creating a two-way dialogue with the groups that have supported them. “A lot of brands try to extract the essence from communities rather than empower communities,” he says. “They take on trending topics if it’s going to help them acquire a lot of reach… [but] they don’t think about how to put time and resource back into them.” He says the Adidas opportunity proves brands are moving that conversation forward. “They’re thinking about how to invest in these people, rather than as something they can just benefit from.”

When asked what his favourite shoe of all time is, Koomson points not to Air Jordans or Stan Smiths but the Clarks Wallabee. Interestingly, it’s the same shoe beloved by another design hero: Jony Ive. “They created an equality through this shoe, you don’t know somebody’s social status. It really represents a lot of different identities and a lot of different groups, and I think that is a very dope concept. That you have a shoe that breaks so many boundaries,” he adds. “That’s what I want to try and achieve.”

The Adidas ZX 8000 BW deadHYPE “Thanos” is available from the end of June.

Comments