Five things to look out for in Jeremy Hunt’s Autumn Statement

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s Autumn Statement will define his time in Number 11 Downing Street and demonstrate a return to orthodox economics following Liz Truss’s ill-fated premiership.

With the backing of prime minister Rishi Sunak, Hunt is expected to raise taxes and squeeze public spending, in decisions the chancellor has described as “eye-wateringly difficult”.

Hunt appears determined to fill a gaping hole in the public finances, and below are five things to watch out for in the Autumn Statement.

A miserable economic backdrop

The forecasts for the economy and the public finances by the UK fiscal watchdog that will be published alongside the Autumn Statement are expected to be bleak.

High inflation that was fuelled by soaring energy prices is hitting living standards and Hunt acknowledges that this is unleashing a recession.

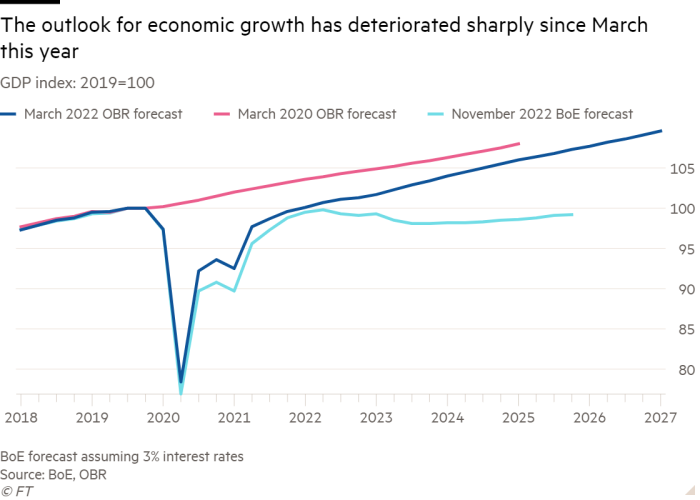

The Office for Budget Responsibility is unlikely to forecast a two-year recession like the Bank of England did this month, partly because the OBR is due to base its estimates on slightly lower interest rates, but this is small comfort.

After a recession expected to run through 2023, the subsequent recovery is due to be slow. Recent data revisions, lowering the level of gross domestic product in the UK, will almost certainly force the OBR to increase its estimate of persistent economic damage caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. There have also been no signs of any improvement in the UK’s feeble productivity growth to pep up the economy.

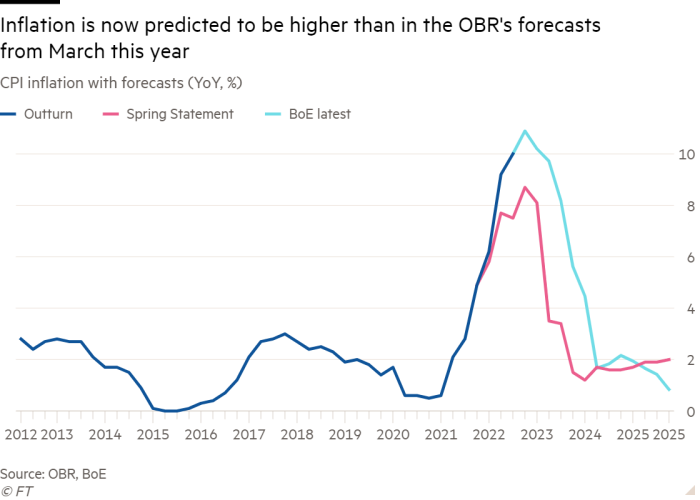

The OBR is due to say that inflation — which hit a 40-year high of 10.1 per cent in September — is likely to peak soon and then come back down to 2 per cent.

The gaping hole in the public finances

At the time of its last set of forecasts in March, the OBR predicted the government would be able to stabilise public debt as a share of gross domestic product by 2024-25 with almost £30bn of fiscal headroom.

But much has gone wrong since then. Inflation at more than 10 per cent has increased the cost of welfare benefits and pensions by more than £20bn a year by 2027-28, according to calculations by the Financial Times.

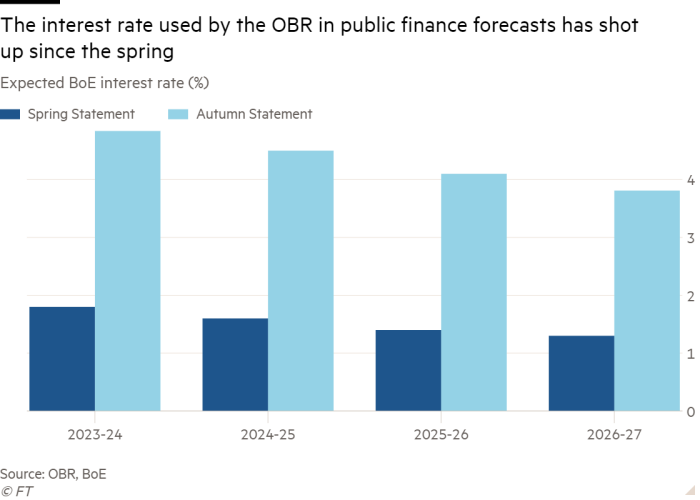

Amid rising interest rates, the cost of servicing government debt is due to increase by more than £70bn in 2023-24 compared with what the OBR anticipated in March, and still be more than £30bn higher in 2027-28.

These two factors alone more than wipe out the £30bn of headroom. Add in some economic weakness hitting tax revenues and Truss’s reversal of a national insurance increase and it becomes easy to see how Hunt was presented with a budgetary hole of about £35bn in preliminary forecasts by the OBR.

On top of this figure, Hunt is keen to build in a margin for error of about £10bn to £15bn so he can say he has a reasonable chance of putting debt on a declining path by 2027-28. He also needs to take account of how raising taxes and cutting spending weakens economic performance and hence lowers tax revenues, making the fiscal hole even bigger.

Treasury insiders said the total budgetary repair job was judged by the OBR to be close to £55bn in 2027-28. That would represent a fiscal tightening of close to 2 per cent of national income, similar to that imposed in 2010 by the then chancellor George Osborne.

Austerity 2.0 is coming

Hunt is looking at filling half of the budgetary hole by freezing day-to-day public spending in real terms in the three years after 2024-25.

In March, the government proposed spending for these years would grow annually in cash terms by 3.7 per cent, but the figure is now likely to drop below 2 per cent. This would save about £27bn in 2027-28, according to FT calculations.

Setting spending plans in line with expected inflation would mean a cut to many public services — a fresh round of austerity to rival that overseen by Osborne.

While health is due to be protected, it will nevertheless be affected: for example a plan to limit the amount someone in England would have to pay towards personal social care, which was due to take effect next year, is likely to be delayed as part of Hunt’s search for savings. He is also expected to trim capital spending.

Taxes are due to be increased stealthily

Hunt has reversed most of the £45bn of unfunded tax cuts in Truss’s “mini” Budget that roiled financial markets and temporarily raised government borrowing costs sharply.

This will not be the limit of Hunt’s actions, and much of it will be stealthy. The largest revenue raiser is likely to be a system-wide freeze in the levels of allowances and thresholds for the next five years, spread across income tax, value added tax, national insurance, capital gains tax and inheritance tax.

A four-year freeze in income tax thresholds implemented in April will raise almost £30bn a year by 2025-26, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a think-tank. Extending this and applying the same principle across the tax system should raise well in excess of another £10bn a year by 2027-28.

Richer people are likely to face some tax increases, such as lowering the £150,000 threshold at which they pay the 45p top rate of income tax, probably to £125,000. This would not raise large sums, but allow the chancellor to say those with the broadest shoulders have borne most of the pain of his budgetary consolidation.

One thing Hunt will not do stealthily is windfall taxes. He is poised to increase the rate of a one-off levy on North Sea oil and gas producers from 25 per cent to 30 per cent, and extend its duration from 2025 to 2028.

The rabbit in the hat?

The chancellor has said the rabbit in the hat — favoured by his predecessors down the years as a means to generate good newspaper headlines — was unlikely to be paraded in the Autumn Statement.

Officials suggested there was so much bad news that any attempted distraction would be doomed to failure.

Nevertheless, there are three potential silver linings Hunt is set to highlight.

First, he is likely to say that benefits will go up in April in line with September’s 10.1 per cent inflation rate. The so-called triple lock — which raises the state pension in line with the highest of inflation, average earnings or 2.5 per cent — is expected to be safe at least until the next election.

Second, the chancellor can point to recent market movements that suggest government borrowing costs are falling gradually. If this trend persists, the OBR forecast for the public finances in the spring should be more favourable.

Third, Hunt will give some indication of the government’s proposed replacement for the cap on household energy bills that expires in April. He is expected to replace universal support for households with a new scheme focused on help for the elderly and vulnerable.

Comments