AstraZeneca on fast track to companion diagnostics

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The green light given by US regulators last month to AstraZeneca for a new lung cancer treatment marked one of the fastest drug approvals on record. This process can sometimes take a decade or more, but the company took just two and a half years to reach market following the first human trial.

One of the reasons for the speed was the highly targeted nature of the medicine, Tagrisso. It is aimed at a subset of lung cancer patients whose tumours have spread and developed a treatment-resistant mutation. This meant trials took place among a relatively small and well-defined group of patients.

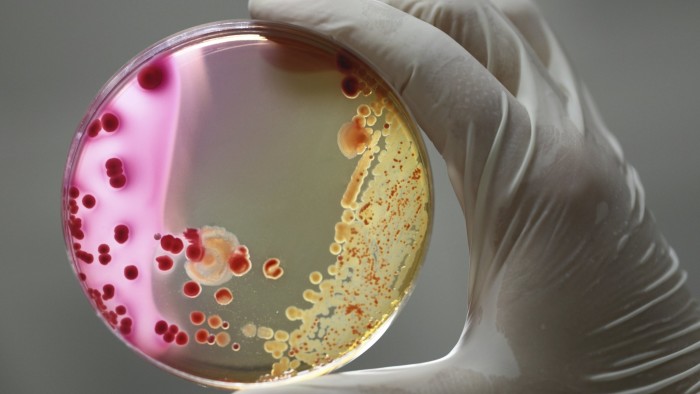

This was the latest example of the accelerating shift by pharmaceutical companies away from one-size-fits-all drugs towards more personalised medicines. Underpinning the trend has been the rise of “companion diagnostics”, which pinpoint the patients who stand to benefit.

For the pharma industry, the rise of personalised medicine means accepting lower sales volumes than those achieved by traditional blockbusters. But it promises to accelerate development and help demonstrate the value of new products at a time when drug prices are facing mounting scrutiny from budget-constrained health systems around the world.

“We can offer a better value proposition if we can identify the patients who will benefit and remove those who will not,” says Greg Rossi, head of the oncology business for AstraZeneca in the UK.

Tagrisso is aimed at non-small cell lung cancer patients (NSCLC) with two genetic mutations called EGFR and T790M. About 10 per cent of NSCLC patients exhibit EGFR and two-thirds of these are T790M positive. AstraZeneca worked with the diagnostics arm of Roche, the Swiss pharma group, to develop a test for the mutant genes.

This marked the second targeted oncology drug launched by AstraZeneca with a companion diagnostic in less than a year, after the approval of Lynparza, also known as olaparib, for ovarian cancer patients with mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes.

The UK-based company has put personalised medicine at the heart of its turnround efforts as old, mass-market blockbusters such as its Nexium heartburn pill and Crestor statin lose patent protection. Half of the drugs AstraZeneca expects to launch by 2020 will come with companion diagnostics and 80 per cent of those in its research and development pipeline are personalised.

Others are pursuing similar strategies. In October, New Jersey-based Merck won approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the use of its Keytruda medicine against non-small cell lung cancer together with a companion diagnostic to detect a protein associated with the disease.

Keytruda is among the leaders in a hotly anticipated new class of cancer drug that disables a so-called “immune checkpoint”, called the programmed death ligand 1, or PD-L1, in a way that frees the body’s disease-fighting T-cells to attack tumours.

However, only about 22 per cent of NSCLC patients have high enough levels of PD-L1 for Keytruda to be effective. This limits the size of Merck’s potential market but promises to reassure healthcare providers and insurers that the hefty $12,500 a month US price is worth paying.

“Pharma is realising that having diagnostics hand in hand with drug development is really important,” says Rudi Pauwels, chief executive of Biocartis, a Belgian diagnostics company. “You cannot have precision medicines without precision diagnostics.”

Roche has been regarded as the leader in personalised medicine since it launched Herceptin for women with HER 2-positive breast cancer in 1998, bolstered by its in-house diagnostics division.

AstraZeneca last year sought to strengthen its own diagnostic capabilities through the $150m acquisition of Definiens, a Germany company specialising in tissue-based tests to identify which patients respond to a drug.

However, Ruth March, head of personalised healthcare at AstraZeneca, said the company had no intention of building a full-blown diagnostics business to match Roche. Instead, it would continue to cherry pick different diagnostic partners for different drugs.

Other developers of companion diagnostics include Abbott Laboratories, Agilent Technologies, Myriad Genetics and Qiagen.

“We have made a strategic decision to go with lots of different diagnostic partners,” says Dr March. “Some companies are stronger in some technologies than others.”

What are the next frontiers in this alliance between pharma and diagnostics? AstraZeneca is one of numerous companies exploring the potential of so-called “liquid biopsies” to detect fragments of tumour DNA circulating in blood. It is hoped this could prove more sensitive than tissue biopsies and allow cancer mutations to be detected at an earlier stage.

Diagnostic companies are also seeking to move beyond companion products for individual drugs to develop more sophisticated tests that can screen for multiple biomarkers at once.

Janet Woodcock, director of the centre for drug evaluation and research at the FDA, cautioned in a blog that, while the industry had made great strides, there was a long way to go: “It is still hard to develop targeted therapies for many diseases because there isn’t enough scientific understanding of why the disease occurs and what biomarkers would be useful.”

The push for greater personalisation was given a boost by US President Barack Obama last January when he used his annual State of the Union address to launch a precision medicine initiative. This included $215m of federal investment in measures to speed the push for targeted therapies.

Watching on as a guest of the US president was a cystic fibrosis patient called Bill Elder. He has been successfully treated with a much-heralded drug from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which targets a genetic mutation affecting 4 per cent of the 30,000 people in the US with the disease.

“That is the promise of precision medicine,” said Mr Obama in a press conference after the speech. “Delivering the right treatments, at the right time, every time to the right person.”

Comments