Developing nations squeezed as virus fuels public spending | Free to read

Simply sign up to the Coronavirus economic impact myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Some of the world’s largest developing economies are set to face a fiscal crisis in the coming years unless they can roll back huge increases in public spending enacted in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, analysts have warned.

The economic downturn caused by the pandemic, combined with rising healthcare spending to tackle the spread of the virus, have caused budget deficits to soar in many countries. They will have to face the choice of risking public unrest by cutting back on spending, or negotiating with investors to restructure their debts.

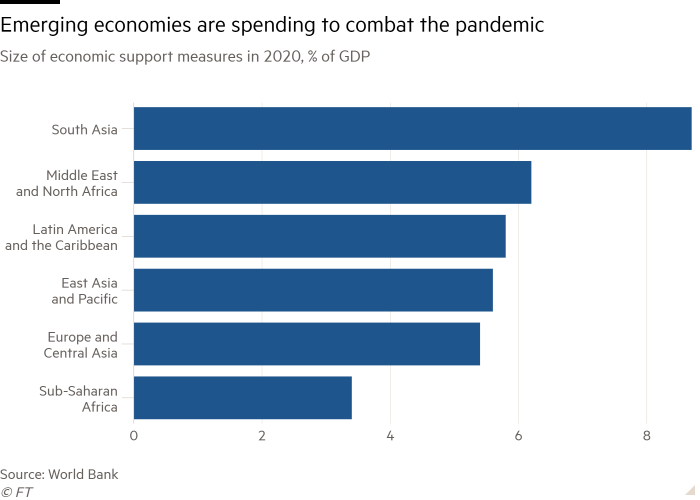

On average, emerging and developing economies have announced support packages worth 5.4 per cent of gross domestic product according to figures published by the World Bank last month; in some countries — including India, Malaysia, Poland, Qatar, South Africa and Thailand — pandemic-related public spending has topped 10 per cent of GDP.

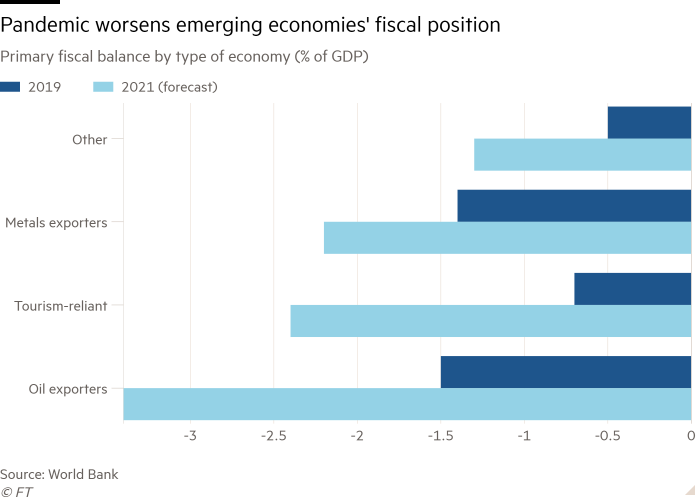

Tourism-dependent economies and big commodity producers are particularly vulnerable, the World Bank said, warning that across emerging and developing economies government debt has hit a record 51 per cent of GDP and many countries which previously ran surpluses have moved into deficit in recent years, leaving limited room for further spending.

Gabriel Sterne, chief economist at Oxford Economics, a research firm, said: “If your response [to the pandemic] is more fiscal spending, then you have to fund it somewhere. So you start to stretch arguments about countries’ capacity to fund themselves.”

In the early stages of the pandemic the IMF warned that emerging and developing countries would need fiscal support of at least $2.5tn to see them through the crisis — in particular, for healthcare spending and social protection.

That figure is now widely regarded as an underestimate: the fund’s latest forecast is that the global economy will suffer a cumulative output loss of $12.5tn in 2020 and 2021, and the majority of the hit will occur in developing countries.

As a result of the strains on public finances, as many as 37 per cent of the bonds in the benchmark JPMorgan index of emerging market sovereign external debt could be at risk of default in the next year or so, according to Adam Wolfe of Absolute Strategy Research.

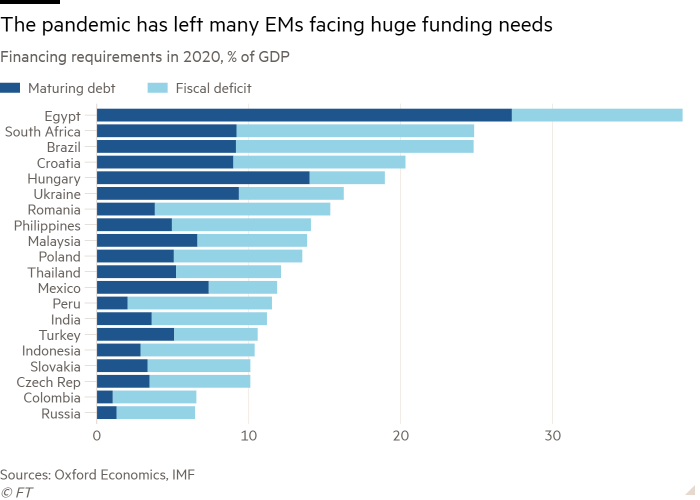

Egypt, Zambia and Ghana are most vulnerable according to his analysis, while large economies such as South Africa, India, Nigeria and Brazil also face elevated levels of risk, and Turkey, Indonesia and Mexico are not far behind.

Brazil and South Africa will each this year rack up budget deficits in excess of 15 per cent of GDP, according to Oxford Economics. On top of this, the need to refinance maturing debt will push their borrowing requirements for the year to 25 per cent of GDP, the consultancy warned.

William Jackson, an emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, said that to keep debt below 100 per cent of GDP, Brazil would need a fiscal squeeze equal to 6 to 7 per cent of GDP a year for several years. Other countries, including South Africa and Mexico, faced similar problems, he said.

“It is hard to see austerity on that scale being politically palatable for any length of time,” he said. “An extremely large number of emerging markets are facing quite severe problems.”

So far many governments have been able to finance their rising debts in the bond markets thanks to a surge of liquidity in global financial markets and local investors’ deep pockets.

The trillions of dollars of stimulus injected into financial markets by central banks in advanced economies has in part flowed through into emerging economies, helping to reverse the massive outflows triggered by the early stages of the crisis.

While $33.5bn left emerging bond markets in March, nearly $50bn has since flowed back in, according to the Institute of International Finance. Governments in developing economies have raised almost $90bn in international bond markets since the beginning of April.

Latest coronavirus news

Follow FT's live coverage and analysis of the global pandemic and the rapidly evolving economic crisis here.

Although the capital flows have helped ease countries’ immediate financial situation, it has also reduced the pressure to find longer-term solutions, while exacerbating their future budget problems by increasing debt interest costs and repayments.

Phoenix Kalen, an emerging markets strategist at Société Générale in London, said: “We are kicking the can down the road in refinancing the debt problem, which is ballooning dramatically . . . It is very tough trying to wrap your head around the extraordinary surge in fiscal deterioration. We have never seen anything on this scale before.”

The IMF and the World Bank have provided emergency funding to help the world’s poorest countries cope with the crisis, and G20 member states agreed earlier this year to give them a moratorium on debt repayment.

But critics say the focus on the debts of poor countries has diverted attention from the fiscal needs of middle-income countries. This weekend’s summit of G20 finance ministers did not produce any further major progress in the discussion of how to go about delivering more widespread debt relief, despite growing calls for action.

Mr Wolfe of ASR said: “In a lot of cases, restructuring will not be enough and countries will need the support of official lending. The size of the problem will be in the trillions [of dollars] while the size of the response has been in the billions, and there doesn’t seem to be much of a plan [to do more].”

And some analysts have warned that the scale of the economic hit to middle-income countries has not yet been widely appreciated.

“We are struggling to imagine what will happen next year,” said Richard Kozul-Wright, director of globalisation and development strategies at Unctad, the UN’s trade and development agency. “We are far less optimistic about a V-shaped recovery than some people are saying. For developing countries, the worst is yet to come.”

Comments