Liquidity is a bigger worry for investor returns than growth

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is chief investment strategist at UBS Investment Bank

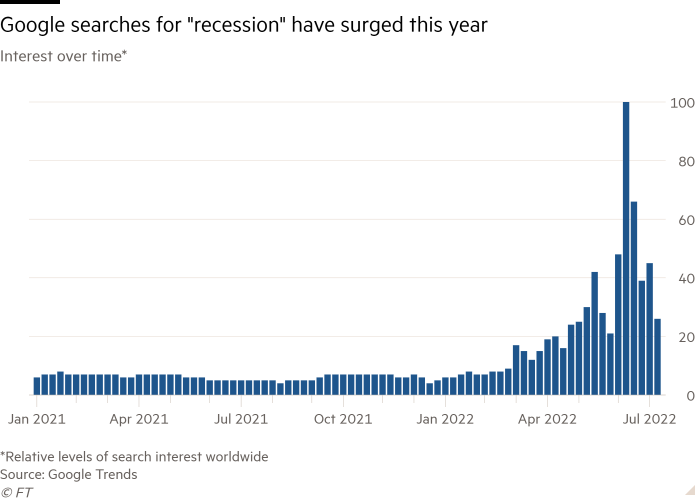

Google Trends’ search count for the word ‘recession’ in the US has risen close to the highs last seen around peak Covid-19, reflecting its centrality in narrative of investors.

However, the markets aren’t pricing in one. Smaller company stocks are traditionally sensitive to economic downturns but have performed in line with, not well below, larger peers across most regions.

Likewise speculative-grade bonds normally suffer in recessions with their spreads over benchmark government bonds rising sharply to compensate investors for increased risk. But such spreads are now at median levels compared with investment grade bonds, not at highs.

The volatility of cyclical currencies like the Australian dollar and the Korean Won is relatively benign. And expectations for peak rate levels for most central banks are being revised higher.

If we look at the signals across equities, rates, credit, commodities and currencies, markets are collectively pricing in global growth of 3.2 per cent. That’s a little lower than long-term average global growth of 3.5 per cent, but it isn’t a recession.

If weaker data raises the likelihood of recession, there is downside risk to the market. Just how much depends on the likely depth of the recession. Of the 17 US recessions over the last 100 years, 7 have been deep, where gross domestic product declined from peak to trough by more than 3 per cent, and 10 have been shallow, through which it declined by less.

The time-weighted average drawdown in the S&P 500 around deep US recessions was roughly 34 per cent. By comparison, the typical drawdown around shallow recessions was only 11 per cent.

A US recession, were one to be seen in the next two years, should be shallow. Strong consumer and bank balance sheets should counter the effects from an initial economic shock.

Some worry that high inflation and rising policy rates lift the odds of a deep recession. History suggests otherwise. Over the last century, inflation has averaged 6.6 per cent ahead of shallow recessions and 2.6 per cent ahead of deep recessions. The average Fed policy rate was 8.1 per cent ahead of shallow recessions and 4.6 per cent ahead of deep ones. There is nothing automatic about high inflation or tighter policy catalysing a deep recession.

If the next recession of developed economies is to be shallow and the market is already down by more than 20 per cent, how can a recession not be already priced?

It’s important to recognise the true driver of the market. Our models show that since equities bottomed in March 2020, liquidity’s influence on the rise and fall of returns has been 2-2.5 times more significant than that of growth. US 10-year real yields have risen by 1.9 percentage points from November 2021, when financial conditions were at their loosest. In parallel, returns were driven lower by a derating of multiples.

Take the market benchmark developed by the economist Robert Shiller, the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio for the S&P 500. Known as the Cape ratio, this compares prices with the average of earnings for the previous decade. it has dropped from 38.5 to 28.7 — although still elevated compared with averages of 14 and 23 ahead of the last century’s shallow and deep recessions, respectively. High inflation and rates may not create a deep recession themselves, but they can cause a significant derating of valuation multiples.

So much still depends on the inflation outlook. UBS takes the optimistic view, expecting US and European inflation to pull back below 2.5 per cent over the medium term as supply bottlenecks ease.

Even if this is realised, however, it is unlikely that US and global equities will deliver returns close to the annualised 10.3 per cent and 7.5 per cent level seen over the past decade.

A switch in liquidity from central bank largesse to a tightening of monetary policy, and the cheapening of bonds relative to equities, point to 5-6 per cent annualised equity returns over the next 5-10 years. Again, that is only if the inflation genie can be put back in the bottle.

Supply chain shifts, rising geopolitical competition and climate change regulation could push inflation higher than our projections. Headline US inflation could track 3-3.5 per cent over the medium-term.

That has historically pushed central banks to tighten liquidity conditions to levels tight enough that would push the S&P 500’s Cape ratio to around 20-22. In this scenario, equities would need to drop a further 20-25 per cent to get there. That’s not a garden variety decline, even if the recession associated with that is.

Comments