Lives interrupted: Caroline Walker’s paintings of female asylum seekers in London

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

“Wow! Look at me! Oh, that’s really nice . . . ” “Oh my God, that’s beautiful . . . ” “Look at that pile of boxes . . . !!”

We are crowded into the artist Caroline Walker’s small north London studio: me, Tereza our photographer, Walker herself, and Joy, Tarh and Consilia, who are identifying themselves in some of the paintings she has put up around the walls.

“Would everybody like tea?” Walker asks. “And there’s cake . . . ”

“Cake!”

“It was my husband who made it, not me,” she admits. “I have to give credit where it’s due.”

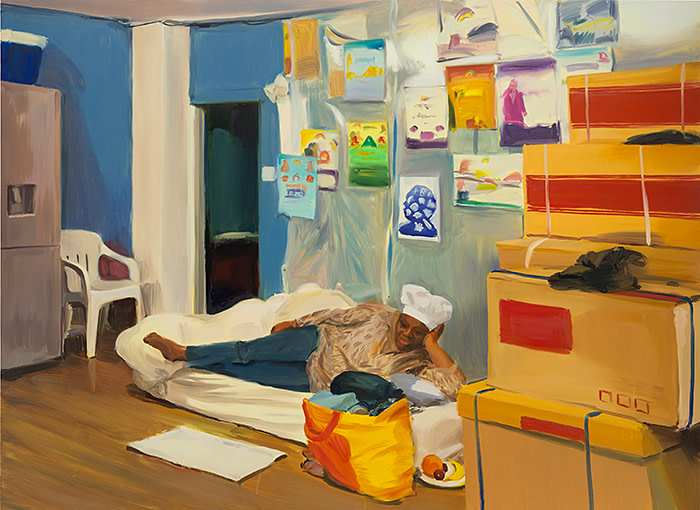

Abi, whose portrait we’ve all been admiring, hasn’t arrived yet but, by anybody’s standards, hers is a striking image: a black woman in jeans and a flowered top, lying on a mattress on the floor of what looks to be a storeroom or maybe a kitchen. She is propped up on one elbow, a hand under her head, and her hair is covered by a white hat. There are posters and paintings on the wall behind her and in front of her on the floor a carrier bag full of clothes, a plate of fruit and a tiny rectangular mat — possibly a towel — that looks as if it’s been put there to make the place seem more like a normal bedroom. If so, the attempt is defeated by a mountain of cardboard removal boxes stacked up to the right of the picture, which balances out the huge stainless steel fridge to the left.

By last autumn, when Walker visited her to make the studies for the painting, Abi had been living in the basement of her church in Brixton, south London, for three years. Like all the other women whose portraits are propped up around the studio, Abi is in the process of seeking asylum in Britain. She ended up in the church basement because she had become homeless and had nowhere else to go.

As they gather around for cake, there’s lots of oohing and aahing over Consilia’s beautifully painted pink nails.

“Oh, Consilia,” Walker smiles, “she’s always got great nails.” But later, when I bring it up again, she says quietly: “Yes, a tiny bit of control in her chaotic life.”

Since March last year, Consilia has been living in the psychiatric ward of a London hospital. Walker’s painting shows her sitting in an armchair with a bottle of nail varnish balanced on her knee. Through a glass partition behind her you can see what looks like a typical ward layout and the decor is that particular shade of turquoisey hospital green. Consilia is from Johannesburg and is a survivor of domestic violence. After having to share a house in London with an ex-partner, she was taken to the hospital after a particularly bad attack. Now she can’t be discharged until she has somewhere safe to go.

This is the first time the women have seen their finished paintings, which are due to be shown in April at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, when it reopens next week after a two-year renovation. Walker is one of nine artists who have been commissioned to make new work for a two-part exhibition, curated by the gallery’s director, Andrew Nairne, called Actions. The image of the world can be different.

The quote comes from a letter written in 1944 by the Russian artist Naum Gabo, who was then living in England, to the art historian Herbert Read. Read has asked him to write about his work for the magazine Horizon, and Gabo lists some of the difficult questions that involves, particularly at a time of war, such as: “What do my works contribute to society in general and to our time in particular?”

“It’s the kind of question an artist might ask now, in the midst of such political and social turmoil,” Nairne says. “‘Why do I make my work?’” His show aims to supply some of the answers. There will be pieces by 38 artists in all, including Richard Long, Callum Innes, Barbara Hepworth, Helen Frankenthaler, Idris Kahn, Melanie Manchot, and Gabo himself. “By the end of the letter Gabo is saying visual artists have a role to play in what the world will be like in the future,” Nairne says. “I want the work to be engaging and attractive and I want to invite artists to be part of it.”

He had been visiting Walker’s studio for several years and wanted to find the right project for her. “Usually, she works with a more constructed environment,” he says. “But I wanted her to be drawn into the sense of real people in a real space.” Walker, who is 35, is Scottish and studied at the Glasgow School of Art and then at the Royal College of Art in London. Her work is loosely figurative — she often works from a model, usually a woman, and chooses the kind of setting she might inhabit. She has painted women in nail bars and women in bathhouses; placed them in fashionable, soulless apartments in Palm Springs and Los Angeles. Her paintings aren’t really portraits but fictional scenarios based on details from real life.

“Andrew wanted me to make some work in response to the refugee crisis,” Walker says. “We did a trip to the “Jungle” camp in Calais. I think perhaps he imagined that was the kind of subject matter I might use, something more politically direct. But I didn’t think it was right for me. I thought, if this is going to work for me, it has to be in London and it has to be about women. So I started to look for some charities and I came across Women for Refugee Women and did some research about them and it seemed like the perfect fit.”

Women for Refugee Women was established in 2006 by former journalist Natasha Walter to support women seeking asylum in Britain. It encourages women to understand their rights and speak for themselves, and helps them navigate the complicated asylum application process, which can take years. Every Monday the charity holds drop-in sessions for about 100 women who come together for English classes, a mums-and-toddlers group, yoga, lunch and advice on issues such as immigration and housing.

Walter invited Walker to come and talk about her work and the project she wanted to do. Some of the women didn’t like the idea and said it wasn’t for them. But a few weeks later, when Walter asked if anybody was interested in taking part, five women volunteered. [Noor, the fifth subject, who is from Pakistan, had been unable to come to the studio to see her portrait.] All of them — and perhaps this is why they felt able to come forward — had been in Britain for several years and were in the process of applying, or even reapplying, for asylum. None were new arrivals. “Obviously I didn’t choose who I worked with,” Walker says. “But in some ways I’m happy it was people that aren’t the headline-grabbers. These are the people that are stuck in the crap system, and they’re the people nobody really knows about because they’ve been here a long time.”

She arranged to visit each of the women wherever they were living. “I didn’t have any idea what the places we were going to would look like. Normally my process is to be quite controlled about that. But after the first visit, I thought, Oh, I’m definitely going to make some work from this.”

Walker begins by taking lots of reference photographs, which she uses as the basis for her paintings, then works them up in a series of small oil sketches. “I suppose I’ll take at least 50 to 100 photographs at each session,” she says. “So, sometimes, I’m collaging things together. I tend not to know till I do the oil sketch what I’m going to find interesting enough to use.

“It’s been a change of direction for me. A lot of my subject matter is very, well, glitzy, I suppose. But this was trying to capture almost the opposite. Not in a way that was heavy-handed, but I don’t normally describe boxes covered in plastic bin bags, or a door that’s got half the laminate coming off it.”

Tarh lives in a hostel for asylum seekers in Southall, west London. “We have 10 ladies staying downstairs and eight men staying upstairs, and lots of children,” she says. “The health and safety procedures are not good: we don’t have a working fire alarm, there is a lot of mould and we have cockroaches everywhere.”

She says the hostel doesn’t feel secure. “The rooms are very small so we have to get rid of most of our things before coming here. Everything is tight, you feel you are living in a small prison cell, not a home. But we cope, because this is better than being on the street. Or doing as I did before, going to sleep on people’s sofas and being like their slave, doing all their domestic work just to have a roof over my head. That is how asylum seekers live. And for a woman it is more dangerous. Women are put in very vulnerable situations just to avoid being on the street.”

How long had she been in the UK?

“Nine years now.”

So you have applied before . . . ?

“Yes, you go from one application to the next. You keep having refusals. We go on with our applications to the Home Office, and they keep disbelieving you and not looking at your claim. So, like with mine, they say it lacks credibility.”

And each time you are refused?

“Yes. You appeal to the first-tier tribunal, then if they refuse again, you go to do a fresh claim, or go to a judicial review. I went through that. I keep going with the process, keep going, it takes some time.

Are you allowed to work?

“No. They [the National Asylum Support Service] give me £36.95p a week [the standard sum has just been increased to £37.75], to feed myself. Most of the rest of the things come from charity: clothes, shoes, bits and bobs for life to go on.”

Walker’s painting of Tarh shows a woman in a red sweater sitting on a single bed with a file of papers open on her knee. The cupboard next to the bed has suitcases and black bin bags piled on the top of it. The woman in the painting looks nervous, a bit wary. “Yes,” she says, “that’s my room. Room 2.”

Tahr is in limbo — one of thousands stuck in the asylum system in Britain, which is notoriously slow and complex. While their applications are pending, it is extremely difficult for them to work and, if they are refused asylum but are unable to return home, they may be left completely destitute, with no right to any support or any housing. She and many women like her seek support through charities such as Women for Refugee Women and others who share their aims. As well as the Monday sessions, the charity runs a drama group currently based at the Southbank Centre, where some of the women get a chance to act and improvise. And once a week a group of them go to the Breakfast Club, a coffee shop in Hoxton, in east London, where they learn different craft skills — sewing, painting, textile design. “It’s great when local businesses offer to get involved like this,” says Walter, “as that really helps women feel more part of everyday London life.”

Joy has been sitting quietly with her plate on her knee, eating her cake slowly, watching the other women as they sift through the pile of sketches, giggling at themselves. “I came to the UK in 2009,” she tells me. She was given refugee status, having arrived from Nigeria. “My employer mistreated me, she beat me. So when I was out of the house I went to the police. She went back to Nigeria, then, because they wanted to arrest her. But she took my passport, my visa, she took everything.

“My asylum application took three years. And then, when I got my refugee status, I stayed in a hostel for a year. Now I have a home of my own, where I can stay and feel safe.”

So at the moment everything is OK?

Not really. Even when refugee status is given, it is temporary and her leave to remain runs out in March. “I have to put in to reapply before it expires.” Since 2013 she hasn’t been able to work, she says, adding: “I had a fall and was rushed to A&E. And since then I have this dizziness, all kinds of pain. I used to volunteer in St Joseph’s Hospice. Now I can’t travel, I can’t go down escalators . . . ”

Is anybody living with you?

“No. It’s only me. I am waiting for my children . . . ”

Where are your children?

“They are in Nigeria.” She suddenly becomes agitated, speaking very rapidly. “Since January 2015, I ave been getting legal aid. But even now the solicitor hasn’t put the application in. Every day she tells me another story. When I went there first, I asked if I would have to pay anything and she said no. Now, this last fortnight, she told me I would have to pay.”

How old are they?

“One is 16 and one is 22.”

She bangs her forehead with the flattened palm of her hand. “I don’t know what is happening. After some weeks I called her, she has all the documents . . . ”

This is your legal aid solicitor?

“Yes, legal aid. When I did my paper the first time they say you don’t have to pay, and now, this one, she says the Home Office wants the money . . . But she told me not to pay!”

She breaks down, almost in tears. Only a few minutes ago she was smiling with the others. Now she’s thrust back into her life. All afternoon they’ve all been so cheerful, laughing and enjoying the paintings, finding out more about each other. But I notice when they sit down out of the limelight, their faces fall back automatically into expressions of anxiety and worry.

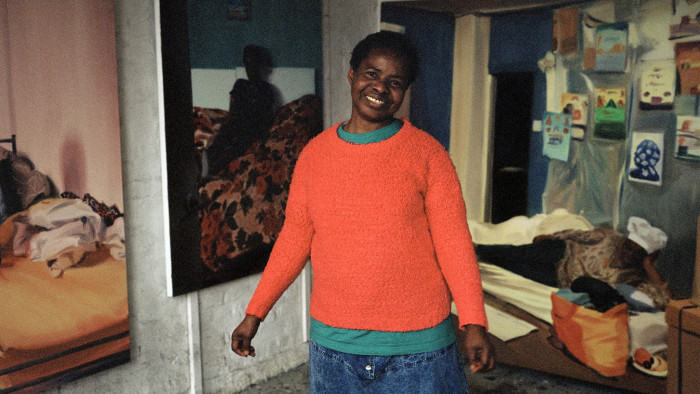

“How come you not eating the cake? I’ll finish it before you know it!” Abi has been the last one to arrive, and she stands in front of her painting, lost in admiration. Her short hair is dyed peroxide blonde. She’s no longer living in the basement. “Because I got harassed there.” Now she is in temporary shelter in south London through a hosting scheme.

She stops at the painting of Joy in her council flat. “You are lucky, you’ve got a big space . . . a big flat! You didn’t ask me to come and stay with you!”

Abi has been working as a midwife on a temporary visa, but is now having problems making a case for asylum or other leave to remain. “I’ve been going round and round and round till now,” she says.

She’s started coming to Women for Refugee Women in 2015. “And I’ve learnt a lot from them,” she says. “ . . . I mean it’s extraordinary things that I’ve learnt in this short period. It’s been just an eye-opener.”

Like what? I ask.

“Like going to the museums. Since I’ve been on my own independently, I’ve not thought of doing all this stuff . . . ”

The others agree: “Yes. It’s more easy . . . ” “With other people . . . ”

They’ve all been invited by Kettle’s Yard to go to Cambridge and see their paintings in the exhibition.

“I would love to go,” Abi says.

There’ll be lots of questions, I suggest.

“And I’ll be glad to answer,” Abi says. “It’s something I’ve been through and I will be glad to share my experience.”

Tereza, the photographer, is preparing to leave. “Do you have a favourite picture Abi?” she asks.

“Yes, The big one. That’s me — relaxin’ with my bowl of fruits in front of me. I wish I had a permanent home of mine. I would love to have this one on the wall!”

‘Actions. The image of the world can be different’, from February 10 to May 6, marks the opening of the new Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge. Caroline Walker’s paintings will be exhibited from April 11; kettlesyard.co.uk; refugeewomen.co.uk

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments