Step into these technicolour worlds

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Shara Hughes first comes into view, I’m somewhat disappointed that she’s not wearing a jungle-print jumpsuit or a Day-Glo, tie-dye hoodie. Both are items of clothing I’ve seen the 41-year-old, New York-based artist wearing in previous studio portraits, complementing and clashing with her intensely colour-saturated canvases. Instead, she’s wearing a plain black T-shirt, and the walls around her are all white. “I just moved into this new place with my fiancé, who is also a painter,” she explains, adding that they’ve recently been debating whether to add their artwork to the walls. Of living with her own fantastical landscapes and floral scenes she says: “I mean, there are lots of reasons not to live with your own work. You can get too critical of it, but I do like to live with a lot of colour.”

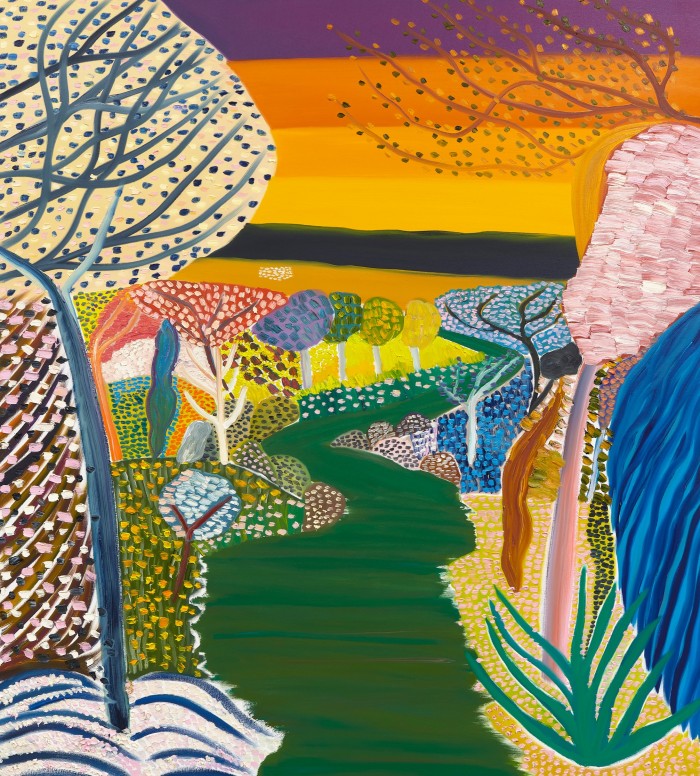

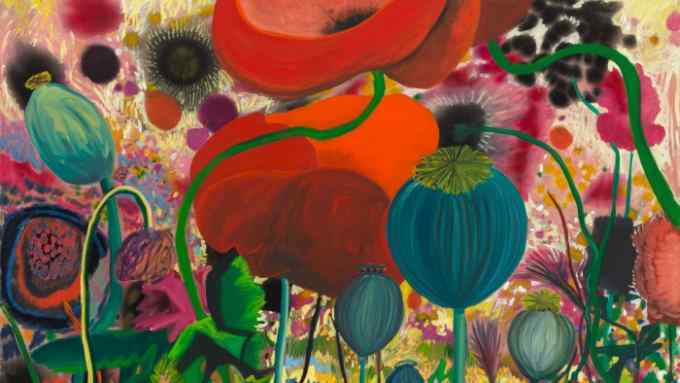

At Hughes’s just-opened solo show at Switzerland’s Kunstmuseum Luzern (until 20 November), a series of 15 paintings manifests the full force of her palette. Imagined landscapes such as My Violet Lullaby (2021) and Its [sic] Not In Your Hands (2019) summon trees and tufts of grass in hot pink, rich red or bright blue, all daubed in Fauvist-like brushstrokes. Her flower paintings, meanwhile, are almost indecently lush, with the likes of Attraction Contraption (2021) offering The Day of the Triffids overtones. They all tread the line between glorious and grotesque. “Colour can draw people in. My work is like, ‘Come over here, look at me, I’m loud,’ but if you spend more time with the paintings, they make you feel uneasy,” says Hughes, whose painterly inspirations run from Milton Avery to Hilma af Klint to Chris Ofili. “A lot of the time, I can have a low-grade anxiety – a feeling that things are not OK, that everything’s out of control. So the paintings sort of show the way that I feel in life. I like the idea of the flower taking the place of a self-portrait, while a landscape feels more like a zoomed-out view of what’s going on personally or emotionally.”

Hughes is part of a new wave of painters who are creating emotional landscapes that blur the boundaries between figuration and abstraction. They recall the art world’s most celebrated colourists – from Matisse to Kandinsky, Howard Hodgkin to Frank Bowling – then push and twist the tones and forms. The results can be energetic and encompassing, as in the work of 29-year-old Londoner Jadé Fadojutimi, on view at her just-opened solo show at The Hepworth Wakefield in West Yorkshire; or sinuous and rhythmic, as with the compositions of 42-year-old São Paulo-based Marina Perez Simão, whose first UK exhibition is at Pace Gallery London until 1 October. While contrasting in style, these artists often use colour to capture memory and experience, or to explore emotions and mental states.

Perez Simão’s paintings can be read as landscapes, with their smoothly arching lines resembling the rainforest or beachside vistas of her childhood in Brazil. “I’m influenced by the drama of nature, and the city too, with its violent winds and heavy rains out of the blue,” she says. “But even when my work is more landscape, there is still a moment in the process that I only think about colours and forms. So, for me, everything is abstraction.”

The new paintings at Pace are “a development. They’re more abstract – more about colour and rhythm. A good composition for me is melodic,” she explains, referencing the influence of music and poetry, ranging from “a lot of French music, contemporary and classical, jazz and [Cape Verde singer] Cesária Évora”, to Emily Dickinson and TS Eliot. “I like his Four Quartets,” she says of Eliot, “but they’re very dense, and I’ve been in a lighter mood lately.” For Pace vice-president Samanthe Rubell, Perez Simão’s compositions “recall the arrangements of John Cage”.

Unlike Hughes, who doesn’t plan her compositions (“I’m really involved emotionally with the painting as it’s happening… so I don’t always know exactly where it’s going to go”), Perez Simão makes preparatory sketches, “sort of rhythmic studies”, and then watercolours. It’s a process she compares to a ballerina preparing for a dance. “So by the time I go to the final painting, it flows easily.” But her choice of colour is not overthought. “Yes, I know colour theory, but I can’t apply it as a 19th-century painter would have; it wouldn’t be relevant,” she says. “What guides me is always my gut. I’ll get obsessed with certain colours. Certainly orange at the moment. Dark reds. Olive green. Combining earthy tones with acid ones. And always yellow.”

Fadojutimi’s use of colour is bold and striking yet light and airy, with gestural brushstrokes layered to luminous effect. “Her paintings almost feel as if they’re lit with an inner light,” says Andrew Bonacina, curator of Fadojutimi’s Hepworth Wakefield show. “There’s an immediacy and an energy in the work. As much as they are drawing on her own emotional experiences, the paintings are a space of projection, a place that people can psychologically step into.” There are visual nods to nature, to plants and flowers, while her points of reference include Japanese anime and film soundtracks. “They’re paintings that teeter on the brink of collapse,” says Bonacina. Her titles, such as And that day, she remembered how to purr or The Prolific Beauty of Our Panicked Landscape, often add further intrigue.

There’s a huge buzz around these artists. Hughes’s paintings have been bought by the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the M Woods Museum in Beijing. In May, her 2017 landscape Spins from Swiss sold for $2.94mn at Christie’s. Meanwhile, Perez Simão’s work is experiencing “passionate demand from private and public collections”, says Rubell, and one of Fadojutimi’s paintings was acquired by the Tate in 2019, making her the then-youngest artist in its permanent collection. In July, Fadojutimi signed with Gagosian; in October, the gallery will dedicate its booth at Frieze London to showcasing her work. “Jadé will create an immersive environment, enveloping visitors in a flourish of colour with her distinctly active, emotive paintings,” says Gagosian senior director Millicent Wilner, who describes the paintings as “internal landscapes” when talking about her work.

Gagosian has also signed 42-year-old Belgian artist Harold Ancart, whose painting practice includes boldly coloured abstracted landscapes, while at Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, perhaps the brightest young star is Rachel Jones. The 31-year-old, Whitechapel-born artist’s vibrant canvases have already been the focus of two solo London shows this year: SMIIILLLLEEEE at Thaddaeus Ropac was followed by Jones’s first solo institutional show at London’s Chisenhale Gallery. In March, her 2019 painting Spliced Structure (7) sold at Bonhams for £910,750.

More boldly coloured landscape paintings can be seen from this October at the Dallas Museum of Art. The Realm of Appearances celebrates Matthew Wong, the self-taught Chinese-Canadian painter who first made waves in the art world in 2018 but died by suicide in 2019 at the age of 35. Curator Vivian Li points to his “obsessive mark-making”, building up varied brushstrokes and dots into rich surface patterns awash with references from Matisse to Yayoi Kusama. That Wong was diagnosed with autism, depression and Tourette’s syndrome adds another reading to the scenes. “Unable to escape his physical and mental challenges, art became Wong’s escape – so he devoted himself to it with an all-consuming intensity,” writes Li in the exhibition catalogue. “There’s been a lot of focus on his mental state, and on the market for his work,” says Li, referencing auction prices that have soared as high as HK$37.7mn (about $4.8mn). “Now, though, we want to focus on his art. And the overall effect of this exhibition is one of hope.”

Common to all these works, perhaps, is that they feel so active. There’s nothing passive about their execution, or in their vibrant, in-your-face results. As Chisenhale director Zoé Whitley observes of Rachel Jones: “There’s something so welcoming about Rachel’s approach to art-making. She often talks about the paintings being loud or rude. They have a really strong personality.” She could be speaking for all of these artists when she says: “These aren’t paintings that are just meant to sit politely on the wall.”

Comments