Why west Africa is trending

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Travel and travel planning are being disrupted by the worldwide spread of the coronavirus. For the latest updates, read the FT’s coverage of the outbreak

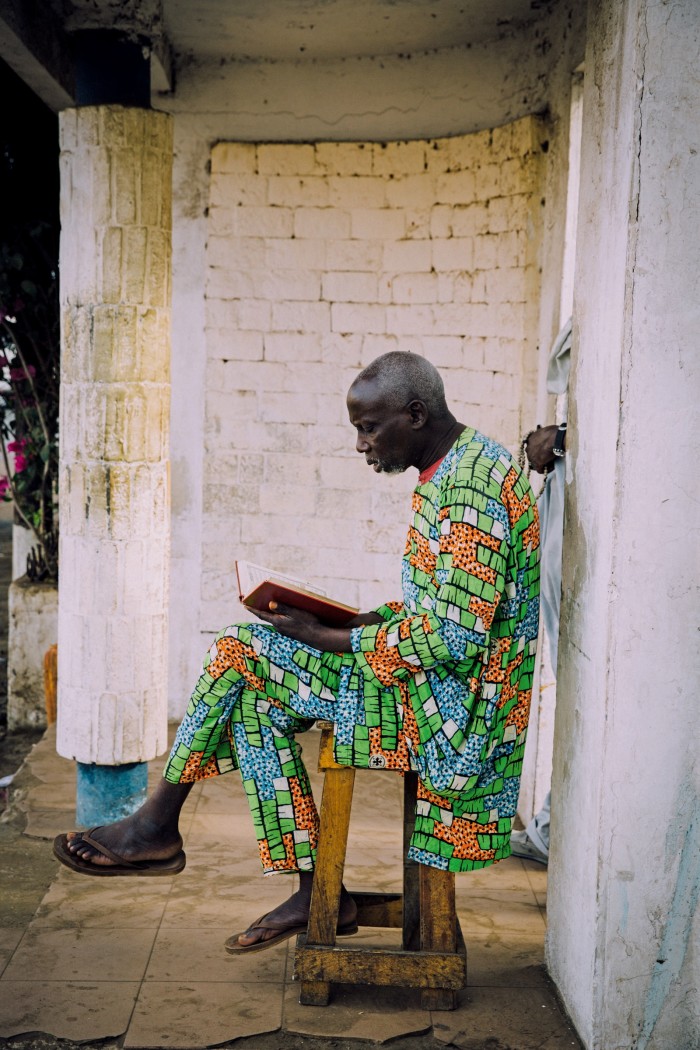

It’s late Sunday afternoon at the Labadi Beach Hotel in Accra. A burst of flamingo pink enters the lobby. The whole family is dressed in the same shade: a young girl in a ruffle-necked dress, boys in matching dickie bow-ties, their mother in a traditional robe, her décolletage ablaze with diamonds as bright as desert moons. Beside the prop-up bar there’s a pianist playing. Beneath an early portrait of Queen Elizabeth II – a nod to Ghana’s colonial history – a doorman in a pillbox hat taps his toe in time with the music’s rhythm. More Ghanaians start arriving in sunflower-yellows, greens and peacock-blues, the women wearing cloth duku headdresses that look like birds about to take flight. It’s west Africa in all its super-abundant glory: sassy, full of swing – a culture making itself heard.

I head into the city to meet my local guide, a photographer I’ve tracked down on Instagram called Jessica Sarkodie (@jessicasarkodie). “I’m one of the returnees,” says Sarkodie. “I used to live in the US. I’m not alone in realising I can have more impact here than I can in the ‘promised land’.” As we Uber our way through town, I’m immediately seduced by Accra’s swagger: arms drape over steering wheels in cabs that toot and push through jams; tables tumble out of bars in the Osu neighbourhood where locals gather at “spots”.

In Jamestown, one of the oldest parts of Accra, we have lunch in Jamestown Cafe, a vibrant gallery with a courtyard restaurant. Three guitarists (@seyrammusic) are practising for a gig later that evening. As I graze on kelewele, a delicious fried plantain, I get talking with Aristide Loua, the Ivorian menswear designer behind the up-and-coming label Kente Gentlemen (@kentegentlemen). Loua fills my head with places and people I need to know, from Accra to Dakar, the capital of Senegal; from Senegalese artist Papi (@l.artrepreneur) to Ghana-based womenswear designer Aisha Obuobi (@christiebrowngh). He connects me to Accra’s Lokko House (@lokkohouse), a mixed-label store showcasing contemporary fashion and objets d’art with a focus on African brands. I buy one of Loua’s tailored blazers there. It’s cut from a natural-dye cotton called kente in Ghana, and kita or baoule in Côte d’Ivoire, which has been handwoven in west Africa since the 16th century.

Loua tells me about another mixed-label boutique in his hometown of Abidjan: Dozo Concept Store, founded by Aziz Doumbia (@dozo.abidjan), which opened in 2018 to promote the region’s fashion and art. And there is Bushman Café (@bushman.cafe), a three-storey villa converted into Abidjan’s hottest hotel and restaurant, owned by a former diplomat and collector of contemporary African art. I add them to my list, which is already packed with boutique hotels, including Dakar’s seven-room Seku Bi (@seku_bi). “There’s a feeling of collaboration, an ambitious desire to work together to make something beautiful and relevant,” says Loua. “The media talks about poverty and political instability. But good stories are also coming out of this region – the new generation is blowing apart the old clichés. A good friend of mine says, ‘God bless Instagram’, and I know what he means.”

While Instagram gives a vibrant virtual window into west Africa, it’s nothing on the real-life tour. Ghana is a good place to start — one of four coastal west African countries on my first visit, which also includes The Gambia, Senegal, and São Tomé and Príncipe, the two-island nation emerging as a new beach destination (the islands’ rising profile has much to do with the investments being made by the South African tech billionaire Mark Shuttleworth and his hotel, Sundy Praia, which opened on Príncipe in 2017). The connections are easy. Accra is one of the main regional hubs, with direct flights to London. From Accra to Lomé, the capital of Togo – a tiny country with a uniquely vibrant festival culture – it’s less than four hours’ drive. Ethiopian Airlines has launched a direct flight from New York to Abidjan, the largest city in Cote d’Ivoire, while Delta is already flying direct from New York to Dakar twice a week. High-end cruise ships are coming in too: Silversea offers 18-day sailings up this coast, from Accra to Lisbon, each spring. This month, the French cruise company Ponant will pioneer a seven-night trip from Praia in Cape Verde, stopping at the pristine Bijagós archipelago off Guinea-Bissau – a Unesco biosphere reserve – before docking in Dakar.

“Foreign travellers have got used to thinking of Africa as a safari holiday. But this side of the continent is about culture,” says Starla Estrada, an expert on the region for the California-based adventure tour operator Geographic Expeditions. “There is a heavy narrative, of course, because of the history of slavery, but the younger generation are trying to move on from that past.” Estrada describes the numerous lures in the region’s surf, art and music, as well as the complex chequerboard of geopolitics and disparate social and economic opportunities. Inequality is a growing issue; according to Oxfam, the top one per cent of west Africans own more than everyone else in the region. Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia were hit heavily by the 2014 Ebola outbreak, estimated to have killed more than 11,000 people – a tragedy in stark contrast to the economic upturns in the region, where the outlook is broadly optimistic.

In 2019, Ghana’s oil reserves placed its economy at the top of GDP growth tables. Senegal is also riding high, with consistent growth and an ongoing record, since independence from France in 1960, of peaceful political transitions. In 2020, Côte d’Ivoire comes to the end of an ambitious four-year National Development Plan aimed to ensure a strong industrial base and to reduce poverty – its Ministry of the Economy and Finance cites a rise in real per capita income of 36.4 per cent. Last year, west Africa’s monetary union agreed to rebrand the France-backed CFA franc as the eco. While the new currency will remain pegged to the euro, countries in the CFA bloc will no longer keep 50 per cent of their reserves in the French treasury, or host a French representative on the currency union’s board. The move is widely viewed as the dismantling of a colonial-era relic in place since 1945.

This pendulum swing – from old narratives to new – is attracting high-end travel specialists eager to pinpoint the next African destinations. “West Africa is sensational in the truest sense of the word, in the sounds, tastes and sights,” says Alice Daunt, a London-based travel agent. “It makes you feel young again in the way it catches you in the colour and current of contemporary life.” Will Jones, founder of the Brighton-based African luxury-travel specialist Journeys by Design, has spent 20 years working on the other side of the continent: “We’ve identified west Africa as the next big opportunity, where there’s a strong cultural and urban counterpoint to wildlife trips.”

I talk about it with Loua, the Ghanaian menswear designer. “There’s a growing sense of ownership about our cultures and traditions. We want to affirm our identity,” he says. Before starting his menswear label, 30-year-old Loua was studying mathematics in New York. “I feel like I’m standing in the crucible of change,” he says. “The diaspora understands the huge opportunities to make business here, and also the necessity of overturning the misconceptions.” He talks about architects such as Olufemison Hinson, originally from Benin, now living and working in Abidjian for Koffi & Diabaté Architectes, designing private homes and commercial retail. David Adjaye, the celebrated British architect of Ghanaian descent, has been tipped for a new Benin Royal Museum in Nigeria; the rotating collection will include treasures currently housed in collections outside Africa – from the British Museum to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As a traveller, and not a particularly hip one, it’s the contrast between the new and old that I find so compelling. Each day I head out of the Labadi Beach Hotel into the cut and thrust of street markets, where tailors and medicine men rub shoulders with evangelists espousing the miracles of Christ into microphones. I long to buy a modern artwork by Zohra Opuku in the city’s Gallery 1957 but can’t afford it; instead I pick up four metres of traditional west African Ankara cloth for $10 to decorate my kitchen table. Within two days, I’m slipping into excess-luggage charges, which only get worse when I travel further north to Dakar where a whole new shopping fever takes hold. Resisting the need to possess every bit of colour I come across – placemats, bowls, key-fobs, cushions, handbags, chiselled gourds – I head out of the city to get a taste of the old country my father described when he worked in rural Ghana as an English teacher in the late 1960s. We pass a Ga funeral – a spectacular affair of palanquins and fantasy coffins carved into giant fish – and press on to attend a ceremony with a voodoo priest.

It’s a tip-off from our guide, Armstrong Koutremon, who works for TransAfrica, a Togo-based tour operator that specialises in west African culture and indigenous festivals. He talks about Festima, the Festival of the Dancing Masks in the Burkina Faso city of Dedougou, where the city’s streets resound with the steady beat of hand drums and the shrill peal of whistles as mask-wearing men and women from 50 villages, as well as other west African countries, converge to honour spirits. Each community is represented by a different mask – antelope, caiman, hare, snake – while griot storytellers hold huge audiences in thrall. I am drawn into his descriptions of Benin, whose Ouidah Voodoo Festival attracts thousands of people in January each year. The faithful come to watch the highest féticheur (fetish priest) pay homage at the Temple of Pythons before festivities move in a parade towards the beach. People dance with hypnotic grace, falling into deep trances, their white robes and richly decorated masks swaying; as the ceremony reaches its peak, a few goats and chickens are sacrificed.

Witnessing spilt blood, however, is not everyone’s idea of a holiday. Starla Estrada shares my misgivings: “There are times when the traditional culture can be very hard to stomach. It’s the real deal, without filter, and so, yes, not for everyone. But the contrasts also make this part of the world unlike anywhere else I know.”

I’m therefore grateful that during the private ceremony I attend in Ghana’s Krobo Province, the priest’s trance is a bloodless event that plays out in the back of a small rural settlement. The drums beat – a low, haunting pulse that sends vibrations through your core. The feet begin to move, striking the ground in rhythmic blooms of dust. The chanting builds, sweat is pouring down the drummers’ backs. Eyes are getting wider. Hips are moving violently, the brush in the priest’s hand rustling through the air. Like everyone else, I’m entranced, the music reaching the parts that words can’t touch. It’s the reason I’ll be coming back to west Africa for more: the wonder that hits you on the sternum just when you thought there was nothing new under an African sun.

Sophy Roberts travelled in Ghana and São Tomé and Príncipe as a guest of Daunt Travel (daunt-travel.com), which offers bespoke west African itineraries from about $1,000 per person per day; and as a guest of Silversea Cruises (silversea.com) from Accra to Casablanca. A similar 18-night west Africa cruise costs from £11,600.

Comments