Two-paced growth holds back global reach of women’s cricket

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Women’s cricket is at a crossroads. In March 2020, 86,000 fans packed Melbourne Cricket Ground for the final of the women’s T20 World Cup.

Here was a game growing rapidly, attracting sponsors and advertisers that were making large returns on comparatively small investments, while engaging a new audience.

Then the Covid-19 pandemic hit. Short-term profit became the priority, to the detriment of sports that were still developing.

And women’s cricket fixtures were scaled back to a greater extent than men’s.

Two countries, Australia and England, have led efforts to continue the game’s development.

Both nations now have strong, high-profile domestic competitions. These have strengthened the calibre of the cricket being played in a remarkably short period.

Australia, at present, has the upper hand, largely by virtue of starting earlier.

Its Women’s Big Bash League was launched in 2015 as a Twenty20 competition alongside the existing men’s version, with fixtures played as double-headers before the men’s matches.

It was a risk at first. “The problem [with double headers] was that there would be a long gap between the two games,” explains Stephanie Beltrame, broadcasting and commercial executive general manager at Cricket Australia, the sport’s governing body in the country.

T20 is sold on being short, sharp and explosive, so enticing spectators to spend long days at a venue was not easy.

“At the time, there were a lot of debates as to whether we should even say on the ticket that the women’s game was on, because the men’s T20 game was created as a [short] three-hour product,” she recalls.

“Internally, we really had to challenge ourselves and say, come on, that’s not right, we need to be promoting both.

“But then we also didn’t want to be giving away your [women’s] product for free, because then there is an insinuation that it’s not worth anything. And underlying it all, you also want to make sure that you’re attracting fans.”

There was an upside, though. “What we did get was coverage of women’s cricket,” says Beltrame. “Because the cameras were already set up [for the men’s game] . . . you get the coverage and you can start to build.”

After this initial television exposure, Cricket Australia decided to make the women’s tournament standalone — with its own window of fixtures, sponsorship deals and broadcast schedule. Viewing figures have risen sharply.

England has taken a slightly different approach. Last year, the governing body introduced the new format, The Hundred — similar to but shorter than T20 and the first tournament where men’s and women’s competitions were launched simultaneously.

All the fixtures are double-headers, with the men’s and women’s games marketed equally.

The first season proved a success for the women’s game: coverage on free-to-air TV showed a large audience that the women’s professional game is very exciting to watch.

Women’s teams, unlike the men’s, did not have to contend with an congested schedule of other domestic competitions, either.

Nevertheless, while England and Australia invest, other nations are falling behind, in both the on-field standard of play and revenue generated.

India has the means to invest. Its men’s game has proved extremely lucrative in recent decades, with a 15th season of the T20 Indian Premier League — valued at $6bn — about to start. However, a women’s league remains a long way off.

Concerns at the depth of talent in Indian women’s cricket is the most cited reason for not taking the risk — though this did not deter England and Australia.

Meanwhile, for those nations without the funds to put into women’s cricket, the future is bleaker. The one-day Women’s World Cup starts in New Zealand in March.

England and Australia fly in on the back of their seven-match, multi-format Ashes series. Sri Lanka, by contrast, have played just two matches in the past two years.

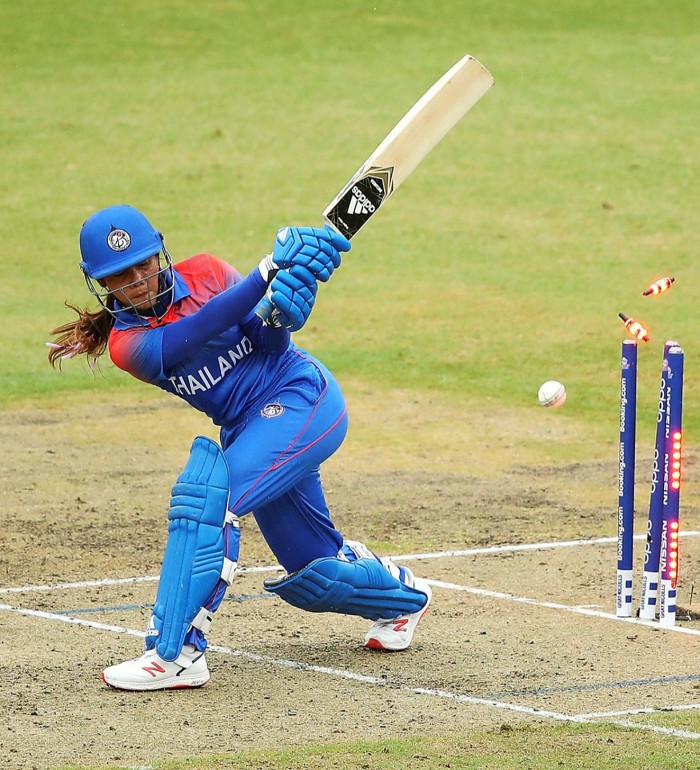

Some teams will be denied the opportunity to compete, for reasons outside their control. Thailand’s women, for example, played in the last T20 World Cup — a feat not achieved by its men — but will not be in New Zealand.

This is because the qualifying games were disrupted by Covid — the Thai women won most of their matches before the qualifiers were abandoned — and by virtue of a rankings system based on nations’ men’s teams.

There is opportunity, but also vast and growing inequality, in women’s cricket.

It will be up to the playing nations and the global governing body, the International Cricket Council, to ensure that the opportunity is for all.

Comments