China Belt and Road dreams fade in Germany’s industrial heartland

Simply sign up to the Chinese trade myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Suad Durakovic, the owner of a truck driving school on the outskirts of the western German city of Duisburg, made it into Chinese newspapers in 2019 by testifying that Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative had triggered a local logistics industry boom.

Today, his business benefits from a shortage of qualified truckers, but not because of China’s global infrastructure development strategy.

“The Silk Road has not developed for us,” Durakovic told Nikkei Asia. “First it was Covid, then it was the Ukraine war, so the boom is no longer about Silk Road logistics.”

Duisburg, a city of half a million people, is located in Germany’s industrial heartland at the junction of the Rhine and Ruhr rivers. A downturn in the country’s steel and coal industries in the 1990s and early 2000s battered its economy.

But the city found a saviour in Chinese president Xi Jinping, who visited Duisburg in 2014 to officially make its inland port Europe’s main Belt and Road hub. While this fuelled anticipation of a new heyday, recent events suggest the prospects are dimming.

Much of this stems from the Ukraine war and Germany’s awkward relationship with China.

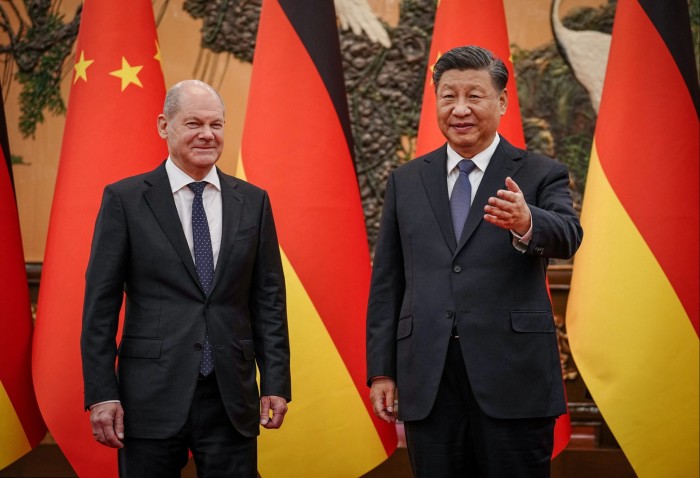

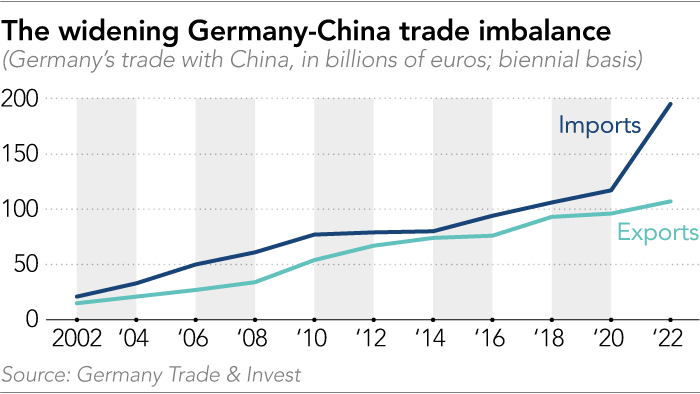

Chancellor Olaf Scholz was the first European leader to visit Beijing after Xi secured a third term as party leader at the Communist party congress in October. But German attitudes have soured recently over China’s cozy relationship with Russia, Taiwan and human rights, as well as Germany’s growing trade deficit with the world’s second-biggest economy.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

Germany is currently reviewing its relationship with Beijing, with the unveiling of Berlin’s new basic guidelines for its China policy expected in the next few weeks.

Draft excerpts show lawmakers urging a significantly toughened stance and a reduction of economic reliance on China. The more drastic prescriptions include limiting investment in China and stricter monitoring of companies overdependent on China for business.

Plans were buried in 2021 for a sprawling China business centre on the banks of the Rhine, from where hundreds of Chinese companies were meant to grow their European distribution networks.

In November, Duisburg cited China’s ties with Russia as a reason for letting expire a memorandum of understanding for a sweeping “smart city” project with Chinese tech giant Huawei.

Russia’s sudden reduction of natural gas exports to Germany fuelled a notion among German policymakers that it was not a good idea to let critical infrastructure fall into the wrong hands.

Around the same time, it became known that Chinese state-owned Cosco Shipping Holdings had in June quietly returned a 30 per cent stake in a €100mn ($108mn) Duisburg port terminal project.

“As state-owned Cosco pulls out, other privately owned Chinese logistics players stay engaged, which suggests that Cosco pulled out of the port terminal project over political headwinds,” said Markus Taube, the University Duisburg-Essen’s professor for East Asia economics and China.

“That event and the expired Huawei deal nurture doubts among Duisburg’s Chinese business community whether Duisburg still is a good place for them to do business.”

The mood has certainly changed since 2011, when the first train on the China Railway Express — an alternative to container shipping — arrived in Duisburg and opened a new chapter in China-Europe land transportation.

The line constituted a key part of China’s efforts to entice electronics-makers to move their manufacturing away from China’s coastal provinces to the Chinese inland, where cities are served by the new train services.

Data by Duisport, the port’s owner and operator, show that pandemic-related disruptions to maritime trade boosted the Silk Road freight rail business, with the geopolitical upheaval stemming from the Ukraine war causing the opposite.

While the annual number of trains rose by 12 per cent to 2,800 in 2021, bookings dropped by about 30 per cent in the spring of 2022, as businesses that adopted rail freight faced reputational, insurance, sanction and confiscation risks along the Russian route.

In late 2022, a port spokesman told Nikkei Asia that although momentum has since improved, figures remain below pre-pandemic days — the share of the China-Europe freight rail business in the port’s overall turnover is now 3-4 per cent.

Nanjing High Accurate Drive Equipment Manufacturing Group (NGC) in 2015 opened its European headquarters in the city for design, testing, maintenance and refurbishment of gearboxes for wind turbines and industrial equipment. The company cited direct train services between Duisburg and its headquarters in Nanjing as one of the main factors for choosing the city.

But one complaint among opposition Duisburg council members is that Chinese companies are not contributing to the local economy.

Nikkei Asia’s research of local trade registers suggests that nearly all of the 100 or so Chinese companies that opened bricks-and-mortar presences in Duisburg are engaged in either logistics or cross-border ecommerce. For example, a company with the Germanic-sounding name Hermann Commerce distributes Chinese instant food, soy sauce and food seasonings to more than 20 European countries.

Chinese-owned Lisstec markets a cosmetics brand with the similarly Germanic-sounding name Hermuna, which is pitched as “Made in Germany”. But the brand only appears to be available for consumers in China despite the company’s Chinese-language Weibo social media account suggesting its products are made in a German factory for sale in German cosmetics stores and pharmacy chain stores.

“The Chinese ecommerce companies that have set up here are not known to be big local job creators or tax contributors,” said Sven Benentreu, the deputy chair of the local chapter of the pro-business Free Democratic Party (FDP), an opposition party in Duisburg.

“We as the FDP appreciate the presence of Chinese companies here, but the strong China focus of the city government is obviously not paying off as expected,” he added.

NGC and the other Chinese-owned companies approached by Nikkei Asia for this article either declined to be interviewed or did not return calls.

Kai Yu, director of the China Business Network Duisburg, also declined to be interviewed, just saying in November that “the Chinese managers I know are unavailable, because they have already travelled back to China for the Chinese new year holiday”.

China is currently celebrating the lunar new year, two months after Nikkei Asia approached Yu.

Chinese students in Duisburg are also not integrating into the city, local academics say.

About 2,000 Chinese nationals are enrolled at University Duisburg-Essen, the largest intake among German universities, due mainly to a city partnership signed between Duisburg and Wuhan in 1982 that encouraged academic exchanges.

Duisburg’s Chinese student population is concentrated in the streets near the university, where there are a handful of Chinese restaurants and shops. Several part-time student restaurant workers said they mainly came from Shandong province under academic exchange arrangements.

“It has always struck me how isolated Duisburg’s Chinese student population is compared to those of other Asian countries, with Chinese community groups effectively shielding new arrivals by assisting in all the initial tasks such as arrangement of accommodation,” said Antonia Hmaidi, an analyst at the China think-tank Merics in Berlin, who previously taught at University Duisburg-Essen.

“China’s deteriorating image as an autocratic rival also made China-centred career planning unpopular among German students,” she added. “The relationship with China has become more politicised than a few years ago.”

“After the German government releases its new China strategy, the overall climate will probably further worsen, which will probably further cool Duisburg’s business relationship with China.”

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on January 24, 2023. ©2023 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved.

Comments