Ditching bond yield cap will be tricky task for new Bank of Japan governor

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Incoming Bank of Japan governor Kazuo Ueda confessed that he did not have a “magical” monetary policy solution to resolve the nation’s decades-long battle to spur inflation when he appeared in front of the Japanese parliament last week.

But as the 71-year-old economist prepares to become the first academic to take the helm of the Japanese central bank in April, there was a crucial hint he dropped at parliamentary hearings that finished on Monday: the BoJ’s policy of capping long-term government borrowing costs through vast bond purchases — known as yield curve control — was unlikely to survive in its existing form under the new regime.

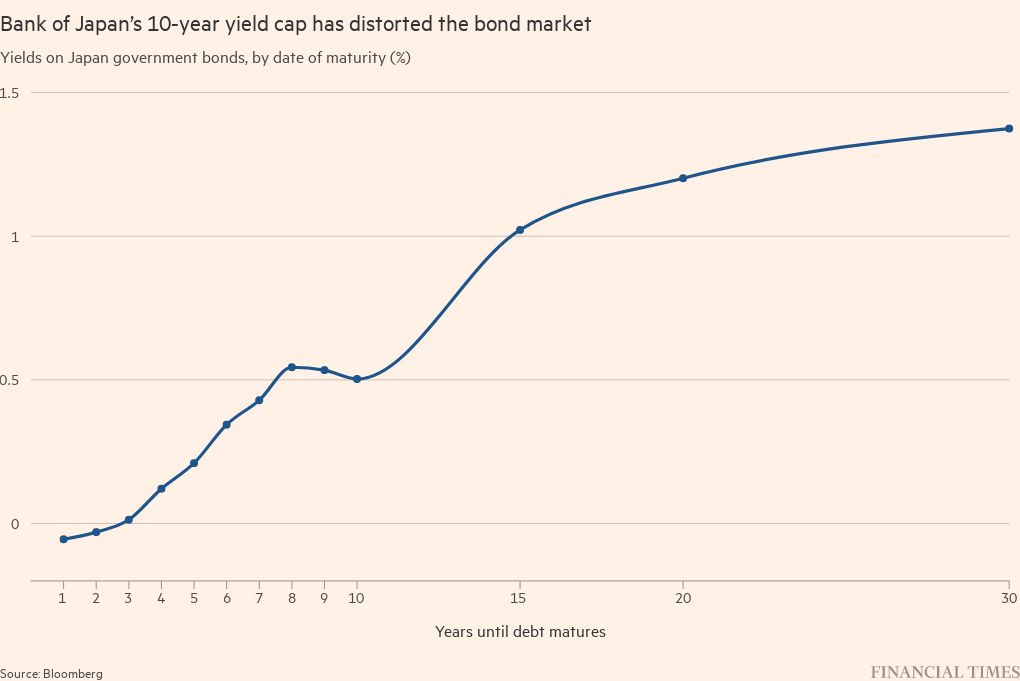

Any change to the BoJ’s efforts to keep 10-year yields rooted near zero will have a significant impact on global financial markets, given the gulf that has opened up between the yields in Japan’s vast bond market and those elsewhere in the developed world, as central banks in the US and Europe aggressively raised interest rates over the past year. If the BoJ allows yields to rise, Japanese investors who have had to look overseas for returns would likely bring their cash home, inflicting further losses on global bonds but boosting the yen.

“Japanese investors are very underweight in the domestic bond market, and would most likely repatriate large amounts of capital that has been invested abroad in the past decade for want of domestic alternatives,” said Deutsche Bank analyst Robin Winkler.

In December, incumbent Haruhiko Kuroda stunned investors by announcing that the BoJ would allow 10-year Japanese government bond yields to fluctuate by 0.5 percentage points above or below its target of zero, widening the previous band of 0.25 percentage points.

The BoJ has since spent about $300bn in December and January alone buying government bonds to defend the new target, and an expanded programme of loans to banks to ease pressure on the Japanese bond market. Even so, investors have not given up challenging the central bank to bow to global inflationary pressures and relax the yield ceiling further, or even scrap it.

The incoming governor suggested last week that a pick-up in inflation expectations could force the BoJ’s hand.

“If the outlook for the price trend improved significantly, we will inevitably have to consider a move towards policy normalisation including a review of yield curve control,” Ueda said on Friday. Even if the inflation expectations do not pick up, he added that the BoJ would need to continue easing measures while reducing the yield cap’s market-distorting side effects.

“Either way, it sounded like he was saying that yield curve control had to be changed in some way,” said Ayako Fujita, chief Japan economist at JPMorgan Securities.

For investors, the big challenge is to determine how the BoJ would go about revising the yield curve controls.

Similar to the IMF’s recommendations, investors are weighing at least three options the BoJ could take: widen the 10-year band around the yield target; gradually loosen its grip on the bond market by targeting shorter-term yields; or abandon the target altogether.

During the parliamentary grilling, Ueda was tight-lipped about what options he had in mind, but he did not rule out shortening the yield target’s duration from 10 years.

“It will be extremely important to maintain dialogue with markets. But in some cases, a surprise factor is unavoidable,” Ueda said.

Some analysts say shortening the target from 10 years to five would reduce the quantity of debt the BoJ needs to buy, making its eventual exit from the market less dramatic. Shusuke Yamada, foreign exchange and rate strategist at Bank of America, said the move would likely weaken the yen if investors assumed that the BoJ would not tighten its policy further once it had revised the yield curve framework.

However, others argue that such a shift would simply serve as an invitation to investors to challenge the new target. Naka Matsuzawa, chief Japan macro strategist at Nomura said the BoJ risked being drawn into a continuing battle with markets. Instead, the central bank could scrap yield curve control but mitigate the market fallout by buying shorter-term government bonds, but without setting an explicit target.

If the inflation outlook improved, JPMorgan’s Fujita said Ueda would likely raise the yield ceiling further, bringing 10-year bonds close to where the market thinks they should trade at about 1 per cent. While that would effectively end yield curve control, most economists expect the BoJ to continue its easing stance with large bond purchases until markets stabilise.

Analysts say the timing of the BoJ’s next move will be tricky. It will need to catch investors off guard to stop them front-running a policy shift by dumping government bonds en masse, but could also destabilise markets if it kept on tweaking the policy.

Japan’s next move will also depend on how much further other central banks — most notably the US Federal Reserve — need to lift borrowing costs to control inflation. If Fed rates continue to rise sharply, the yen is likely to once again fall to a multi-decade low against the US dollar on wider interest rate differentials.

According to Matsuzawa, some non-Japanese investors are betting that Kuroda will once again tweak his yield curve policy when he chairs his last policy board meeting next week. But most economists expect the change to be made under Ueda as early as the summer.

For Ueda, ending yield curve control would just be the start of the enormous task of extricating the BoJ from financial markets. In addition to more than half of Japanese government bonds, the central bank also owns a majority of locally listed exchange traded fund assets.

Unwinding the ETFs would also pose “a huge problem” if the BoJ were to exit from its ultra-loose monetary policy, Ueda said: “It’s a difficult and tough situation for whoever takes on this role, . . . but that’s exactly why I want to take on this challenge.”

Comments