Corbyn, Macron and D66: the elections that shocked the political class and why it’s not over yet

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

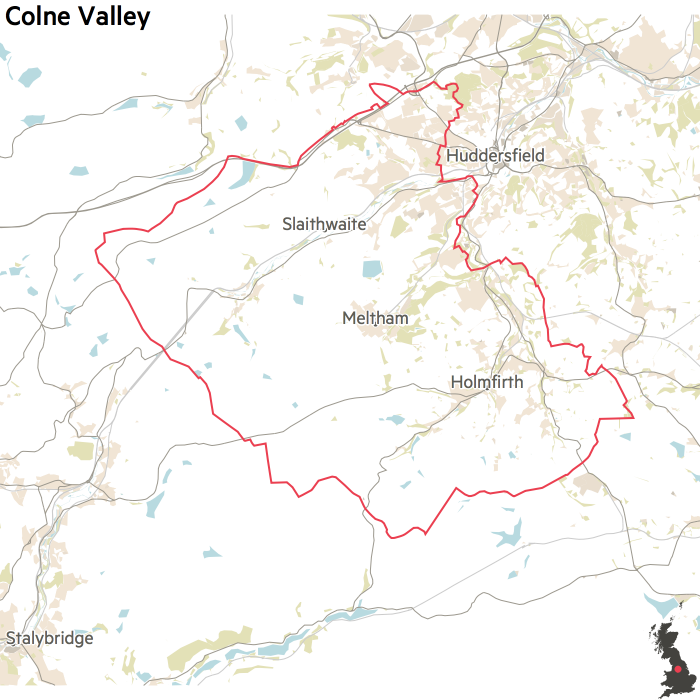

Since January, three European elections have produced results that have upended conventional wisdom and defied expectations. Why did this happen and are there links between them? In the latest update to our Europopulists series, we visit three places — Colne Valley in the north of England, Garges-lès-Gonesse in the Paris suburbs, and North Amsterdam — to find out how the political ground is shifting

Colne Valley

‘We’re right in the middle of it. This is still happening’

It was a month after the UK’s general election and Jason McCartney still wore the wan smile of a politician who had increased his vote tally by more than 2,600, clinched his party’s best-ever local performance — and lost his job.

The up-and-coming Conservative MP’s defeat in West Yorkshire’s Colne Valley constituency, by a mere 915 votes to a first-time Labour candidate, was one of the shocks of a shocking British election. Sitting in a local café — and occasionally interrupted by well-wishers — Mr McCartney was forthright about the reasons for his loss. “We had an appalling manifesto with nothing to sell,” he complained.

The cautious campaign run by Prime Minister Theresa May was all the more leaden set against the electrifying rise of Jeremy Corbyn, the unapologetically leftwing Labour leader whose support has grown since the election. After obsessing about Brexit for the past two years, voters seemed to catch the Conservatives off-guard by swinging their attention to the state of health and education services.

In Colne Valley, a scenic collection of villages in northern England once dominated by textile mills, the planned closure of the local hospital’s accident and emergency department provoked particular fury. Labour activists made shrewd use of social media to channel that anger.

All that is true. And yet it does not seem to account entirely for the demise of a popular local son whose diligence as an MP was praised even by his opponents, one who strained in polarised times to present himself as an amiable, non-political soul of his community: “Just Jason.”

It seems the well-liked Mr McCartney fell prey to a larger beast that is unsettling British politics. Even if many cannot articulate just how and why, there is a palpable feeling among Colne Valley residents that the previous arrangements and rituals that organised political life are no longer holding. The same upheaval that claimed Mr McCartney might just as easily claim his successor, Thelma Walker — or almost any other politician who dares stand before the people these days.

“It’s almost like the scales have fallen from people’s eyes,” said Mrs Walker when I spoke to her later in London, noting that voters had become jaded by spin and suspicious of professional politicians. “What’s happening in politics is a sea-change.”

Her husband Rob, a local Labour councillor, used words like “fickle”, “polarised” and “pissed off” when describing today’s voters. “The [parliamentary] expense scandal and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have really damaged politicians,” he explained. Mr McCartney, who was on his way to meet an executive recruiter to discuss the next phase of his career, did not disagree. “It’s very easy to be in opposition in politics these days and be populist,” he told me.

If British politics is now in flux, one culprit is last year’s EU referendum. It prompted voters to break with their parties’ official line in droves, introducing a shock to the system that is still reverberating. Once voters stray, argued Andrew Mycock, a reader in politics at Huddersfield University, they are more likely to do so again, loosening traditional bonds and pushing politics in unpredictable directions.

“If the politics of the west is in chaos, so is the electorate,” Mr Mycock said. “And there doesn’t seem to be any pathway to a more stable framework. It’s not going back to what it was.”

Meanwhile, people in the Colne Valley are still struggling to understand what happened on June 8. “It’s probably the most complicated political time that I’ve experienced,” said Victoria Minton, a Labour supporter and veteran of many local campaigns. Sitting in her sun-drenched kitchen, with the latest copy of the London Review of Books on the table, she gave the impression that endless cups of tea and debate would still not allow her to make sense of “the different strands of why people voted the way they did”.

Of Mr McCartney, she said: “He was popular in terms of looking after the constituency.”

—

Thelma and Rob Walker met 35 years ago when they were both teaching at the same school near Manchester. They were flying home from an Easter vacation in Italy when Mrs May surprised the country by calling a snap election. Switching on their phones, they discovered a queue of messages from friends and Labour party members asking whether Mrs Walker would stand.

“We thought: What’s happening?” she recalled.

A former headteacher of two local schools, Mrs Walker was well-liked and well-known by generations of pupils and their parents.

Still, the oddsmakers gave Mr McCartney a 99 per cent chance of holding his seat and expanding the 5,378 majority he won two years earlier. In a sign of the Tories’ intent to dominate the area, Mrs May chose nearby Halifax to unveil her manifesto. So hopeless seemed Mrs Walker’s cause that some friends confessed to feeling they should abandon her to campaign for other Labour candidates who might actually have a chance.

One supporter, Hester Dunlop, a GP, had not planned on even opening the Red & Green Club, a left-of-centre club, for election night. But two days before the vote, Mrs Walker’s agent called up and suggested she do so. It was the first hint that they might be in for a surprise.

“We were all in a state of shock when she won, to be fair,” Ms Dunlop said.

—

Colne Valley has experienced political upsets before: In 1907, a fierce young orator and working-class champion named Victor Grayson stunned the nation when he won a by-election to enter parliament, becoming one of the first socialist MPs. He disappeared 13 years later under mysterious circumstances.

A century before that, Colne Valley was a hotbed of the Luddites — skilled handloom workers who destroyed machinery in the area’s thriving textile mills. Some were locked up in a grand but now derelict building in Milnsbridge — near the Red & Green Club — for the murder of a local mill owner. They were hanged in York in 1813.

“The valley still echoes with the clang of Luddite hammers on the labour-saving machinery; with the stealthy tread of long-dead men on the way to illegal trade union assemblies on the moors,” Reg Groves wrote in his 1975 book The Strange Case of Victor Grayson.

Still, the Colne Valley was less fertile for organised labour than other parts of the industrial north. That is in part due to geography: its hills and valleys tend to isolate nearby communities from one another. It may also be because textile workers were traditionally paid by the item, making collective contracts less appealing.

“It’s small-time chapel thinking — there aren’t big movements here,” explained Mrs Minton, who moved to the Colne Valley 38 years ago, and consequently, is still regarded by locals as a “comer-in.”

The parliamentary constituency has historically been a toss-up between Liberals, Labour and the Conservatives. One person described the Liberals as a comfortable fit between socialism and the “ownership class”.

It is more diverse than it might seem, stretching from the edge of Huddersfield, a city that endured the decline in textiles better than others because it specialised in high-quality cloth, to bleak and windswept moors.

A pocket of the constituency is heavily inhabited by Kashmiri immigrants and their descendants, and has struggled with integration. At the same time an influx of wealthy commuters who work in Leeds and Manchester is pushing up house prices in idyllic villages like Slaithwaite (pronounced “Slowit” by the locals) and sprouting urban accoutrements like gourmet coffee and yoga. The fast-growing Huddersfield University has brought students and public-sector jobs.

“It’s a bit of a microcosm of the country, really,” Mrs Walker said. “Some people are doing pretty well working within certain elements of the private sector . . . But then a lot of people are struggling, really.”

Sipping a coffee in the atrium at Portcullis House, the Westminster building where MPs have their offices, Mrs Walker confessed she was still learning the basics: how to get picked to ask a question during a debate; to remember to nod to the speaker upon leaving the chamber. Still, she does not appear easily daunted. “Would it be arrogant if I said I thought I could win?” she asked, reflecting on the campaign.

As a teacher at all levels of education — from primary school to university — she had watched the way that MPs changed policies, often with little real-world experience of them. “Nothing embeds,” she complained. A particular source of irritation is the way the Conservatives dropped Labour’s “Every Child Matters” education programme when they came into power just as she saw it beginning to work.

“The public are jaded with spin,” she told me. “They’re wanting authenticity.”

Even after Labour’s defeat in the 2015 election, there were reasons for optimism for those who looked closely enough: Its Colne Valley membership more than doubled — many of them younger voters. A year later, Mr Walker succeeded at becoming Slaithwaite’s first Labour member of the district council since 1980. For those seeking authenticity, Mrs Walker was rooted in the community — not parachuted in from afar like the party’s previous candidate.

Above all, though, immigration and Brexit no longer seemed to be the dominant issues for many voters, as the Walkers discovered on the doorstep. Instead, it was austerity and cuts to local services, the ground on which Labour wanted to fight.

“The Conservatives made it out to be a Brexit election — it wasn’t in the Colne Valley,” she said.

“It was shifting,” Mr Walker agreed, adding: “There is a view that austerity is just an endless downward spiral. If you live in Surrey versus a Yorkshire valley it’s quite different and I think people have become angry about that.”

Much of their anger settled on Huddersfield Royal Infirmary, and a plan announced last year to close its accident and emergency department and shift the service to a hospital five miles away in Halifax. The plan is an attempt to plug an annual healthcare deficit that reached nearly £30m in 2015. Many in the valley believe Huddersfield is being sacrificed only because the rival hospital, Calderdale Royal, was built through a private finance initiative — or PFI — and needed more patients to service its enormous debts.

“Quite a lot of people became politicised,” said Mrs Dunlop, who joined a campaign to save the Huddersfield hospital. As a doctor, she described the NHS’s deterioration as “like watching a huge great cathedral being pulled apart brick by brick.”

Even before, many had begun organising over talk that one of Slaithwaite’s two local surgeries was to be closed. They took to Facebook, where a campaign group formed to save the hospital, drawing in folks Mrs Dunlop had not previously considered political, particularly women. “Lots of women stepped up,” she recalled.

Mr McCartney did, too. He raised the issue in parliament and helped the campaign group collect petitions. Still, he became a target as Labour relentlessly linked the Huddersfield A&E to the Conservative government’s austerity policies. It did not seem to matter that Labour had been a big supporter of PFI deals under Tony Blair after he became prime minister in 1997. “This is a national issue. It’s about problems of funding,” Mr Walker explained, calling the NHS “the key issue” in the campaign.

The Huddersfield Facebook group backed Mrs Walker, who in the waning days of the campaign promised that a vote for her would help save the hospital — a promise that some believe was simplistic.

“There’s no easy solution and I don’t think Labour will say there is,” Mrs Walker acknowledged. But her opponent, she argued, had erred in thinking it was enough to be an affable presence at local events when the community wanted someone in Westminster to fight government policy. “People became aware of his voting record down here,” she said.

—

Mr McCartney says he never believed the Conservative landslide predictions. In fact, months earlier, when Mrs May was seeking his support in the party leadership contest, he claims to have warned her against calling an early election. He sensed growing unhappiness with schools and hospitals among his constituents and believed the party needed to demonstrate it was addressing these issues before going to the voters.

Now 49, Mr McCartney built his political persona as a mild-mannered pragmatist rather than an ideologue. He skipped university and instead served in the Royal Air Force in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has the likeability of a television journalist, which he once was. He was a Liberal Democrat briefly before joining the Conservatives.

If he was nervous about the election, his sense of gloom deepened after Mrs May visited the area in mid-May to unveil the manifesto. Her arrival should have energised the campaign. Instead, it showed the radicalising effect of the hospital campaign as gangs of angry protesters confronted the prime minister’s campaign bus in Halifax.

Mrs May compounded the error by later telling the Huddersfield Examiner that the discontent over the hospital closure was “scaremongering” — a remark that undermined Mr McCartney. “That went down like a lead zeppelin,” Mrs Walker recalled.

By contrast, Mr Corbyn received an unexpectedly warm welcome when he visited Beaumont Park in Huddersfield two days earlier, with Mrs Walker at his side. The microphones failed and so the Labour leader was forced to use a handheld megaphone to address the crowd — which only seemed to enhance his charm.

In the end, Mr McCartney’s vote rose to 27,903, a 1.7 per cent increase from 2015. But Mrs Walker swelled Labour’s vote nearly 13 per cent to 28,818.

With such a narrow margin, all groups were pivotal. The Crosland Moors neighbourhood that is heavily Muslim supported Mrs Walker nearly unanimously, repaying her repeated visits to the community — both before and after a terror attack in nearby Manchester by a suspected Islamist extremist set locals on edge.

“People felt they could connect with her. She’s a former headteacher,” said Mohammed Imran, 39, a volunteer at a local mosque. Politicians returning from London tend to seem out of place when they arrive in their local constituency, he observed. “The feeling you get with Thelma is the opposite.”

Undoubtedly, a key demographic was the 10 per cent of Colne Valley voters who in 2015 supported the UK Independence party (Ukip), which advocates Britain’s departure from the EU. The party has been imploding ever since its success in the referendum on leaving the EU in June 2016, and did not even field a candidate in Colne Valley this time, apparently not wanting to siphon support from Mr McCartney, who supported Brexit. Many of its voters joined him, it seems, but not as many as hoped.

“If you’re angry with the government who would you go to?” Mr McCartney asked. “Probably Corbyn. Because he’s angry as well.”

Mr McCartney appears to have come to terms with his defeat, mostly. “I’m proud. My vote went up,” he said at one point. But there is one element of the campaign that has left him bitter: the use of social media.

Far from drawing in enthusiastic new voices and rejuvenating local democracy, Mr McCartney believes it became a vehicle for hard-left activists to demonise him.

He produced his smartphone, showing a series of memes featuring him — some twisting his positions; some simply abusive. Anything positive that might be said about him on Twitter, he noted, was instantly attacked by dozens of trolls. “There’s an army of leftwing activists and sympathisers using it very effectively, sometimes to distort things,” he complained.

At hustings he was routinely heckled as soon as he opened his mouth. His signs were vandalised. “It’s Corbynite politics,” he said. “For all his talk of kinder, gentler politics, he’s stirring it up.”

The result, Mr McCartney argued, is that it was becoming harder to have a reasoned debate about issues like the hospital crisis that requires more than 140 characters. The PFI background to the local hospital crisis “takes a minute to explain — Labour just says: ‘Tory cuts!’” he shrugged.

“Across the world now — whether it’s France or Germany or even the US — it’s hard [for politicians] to make tough choices,” Mr McCartney despaired. “I’m worried where it’s going.”

Most local Labour party members — but not all — reject Mr McCartney’s charges. The Tories ran a nasty campaign, too, they complain — aided and abetted by a tabloid media that has delighted in savaging Mr Corbyn. Still, they acknowledge that it is a fact of social media that it cannot be controlled.

Yet even if Mr McCartney’s complaint is correct, it misses a separate truth: that the Conservatives may have lost sight of how to use social media as a campaign tool.

Edward Kaye, an 18-year-old student who helped the Walker campaign, was particularly surprised by the Conservatives’ tendency to broadcast professional-looking adverts on their official social media accounts. “People just didn’t respond well to that,” Mr Kaye said.

By contrast, Labour supporters took smartphone video and other amateur clips and posted them directly on people’s timelines so that they could share and re-share them in a more natural way. “Our organic shares were the most important part of what we did,” he explained, noting that a single clip racked up 200,000 views. “We didn’t pay a cent for it.”

Mr Corbyn — a candidate who advocates dated socialist ideas about centralising control of the economy — turned out to be an unexpected object of inspiration for a hands-off, user-generated campaign. “He’s kind of a blank canvas to paint different types of politics on,” said Mr Mycock, the academic. “Different people saw different things in him.”

With seemingly little to lose, the Labour party “kind of let a thousand flowers bloom”, he said.

For young, university-bound voters such as Mr Kaye, one of Mr Corbyn’s biggest appeals is supposed to be the promise of free tuition. As it turns out, Mr Kaye does not agree with it — but he does not terribly mind it, either. “Older people are bribed at every election,” he shrugged.

Instead, he appreciated the way the Labour leader had managed to cut through a tired political process. “He has hit on something in politics,” he said. “Gone are the days of stale press conferences with scripted questions and answers . . . It’s not the way to do things any more.”

—

That yearning for authenticity is not limited to young Corbynites in Colne Valley. A 40-something Ukip supporter expressed a similar sentiment.

“The only two politicians I could vote for was Nigel Farage and Jeremy Corbyn,” he told me. “Why? Because I believe them.”

He wondered why the mainstream parties were needed at all in an age of the smartphone. Why not just put things directly to the voters through a series of referendums, such as in Switzerland? Why not allow citizens to serve as MPs at random, as if selected for jury duty?

“The party system is not fit for purpose,” he concluded. “Well, it is fit for purpose: to maintain the status quo.”

To frustrated voters in Colne Valley, that status quo includes the disastrous Iraq war, a parliamentary expenses scandal that showed the division between politicians and the people, the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent years of austerity.

“The expenses scandal, in particular — in which MPs were discovered to be charging such things as the cleaning of a moat on a private estate and the building of a duck house — clarified the division between “us and them,” said David Brook, 55, who was raised in the Colne Valley village of Golcar.

The first member of his family to attend university, Mr Brook’s life changed after a US venture capital firm bought out the equestrian outfitter where he was chief financial officer. He now devotes much of his time to restoring The Swan pub he bought beside his home — something, he quips, that is a matter of “civic duty”.

If fluid, unaligned voters are the future, then Mr Brook may be ahead of his time. Over the years he has supported Margaret Thatcher, who he praised as “transformative”, Mr Blair, who he deemed a “breath of fresh air”, and then David Cameron because the Labour government had “run out of ideas”. In 2015, he turned to Ukip, and then voted for Brexit during last year’s EU referendum.

“The referendum is the great hand grenade that’s thrown all the pieces up in the air,” he observed.

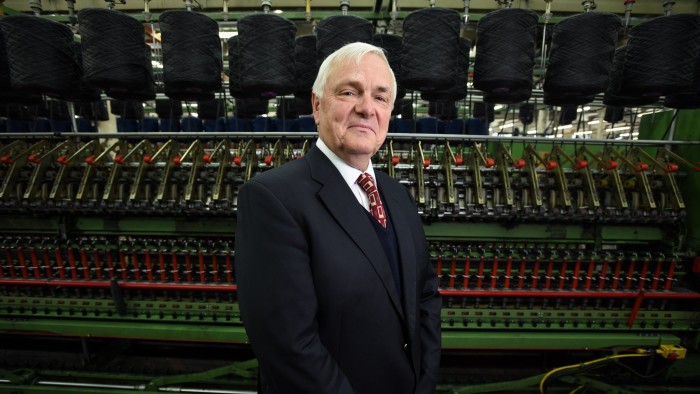

Richard Brown, who has worked in the valley all his life and, at 63, now owns one of its last working textile mills, also voted for Brexit, in part because he believes the EU is corrupt.

“I’m one of the ignoramuses from the north of England, one of the great unwashed,” he said with a wry smile. Later he expressed the locals’ detachment from Westminster, telling me: “In the provinces, politics is something that’s done to people.”

The subsequent drop in the pound has given an unexpected boost to Mr Brown’s mill, Spectrum Yarns, which is now booked with work until Christmas. Still, he has the apprehension of an industrialist at a time when workers are being told the bosses are the enemy. More than anything, he seems to crave stability so that he can make plans.

“[Brexit] was a vote against the political system because a lot of people think they’re ignored by the political class. Jeremy [Corbyn’s] genius is to make them think they’re not,” Mr Brown said. Then he added: “His great weakness is he can’t deliver.”

The problem with young people, he complained, was that they did not remember the 1970s.

In June, Mr Brook decided to return to the Conservatives after undertaking an unusual exercise: reading each of the major party’s manifestos and taking them, more or less, at their word.

“There’s no question he’s a man of principle. He’s stuck by his beliefs since the 1970s,” he said of Mr Corbyn. While he agrees with the Labour leader that voters — particularly in the north — have been ground down by years of austerity he simply does not trust the party to provide the remedy.

Mr Brook was also offended by a promise to save the local hospital he does not believe Mrs Walker could ever fulfil. “It was a lie — a blatant lie to the people of the Colne Valley. And shamefully, it worked,” he said.

So where will Mr Brook and the Colne Valley head next in their political journey? Where will the nation? He did not seem to know for sure. Ukip could return, he predicted, citizens could take to the streets “with garden spades” if the Brexit vote is not respected. Equally, Brexit could mean more austerity, and so an even stronger reaction against austerity.

“The last two-and-a-half years of politics in Britain has been more interesting than at any time in my life,” he said. Then his face lit up: “We’re right in the middle of it. This is still happening!”

Letter in response to this analysis:

It makes sense to extend the two-year timetable as a way out of this debacle / From Stephen McCarthy

Comments