Interior lives: women designers step out of the shadows

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

There is a famous story attached to the early career of the great French designer Charlotte Perriand that goes some way to understanding why so many gifted women designers have long been unfulfilled and undervalued. When Perriand was only 24, she applied to work in the studio of Le Corbusier. She was turned away with the immortal words: “We don’t embroider cushions here.” Merely a month later, so history relates, furniture (in aluminium, chrome, glass and leather) created for her apartment was reimagined as a bar in an installation at the 1927 Salon d’Automne exhibition in Paris. It was a thrilling aesthetic embodying the new “machine age”, and Le Corbusier was blown away. Perriand was hired and so began her 10-year collaboration with the designer and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret.

But for all the visionary work she did with Le Corbusier – and later with the French painter Fernand Léger in the 1930s, then the architect Jean Prouvé during the 1950s – it’s only relatively recently, some years after her death in 1999, that the wider world has begun to understand Perriand’s importance. Some 476,000 people queued to see the hugely successful Fondation Louis Vuitton retrospective of her work in Paris in 2019.

This year, London’s Design Museum is set to pay homage to Perriand with an exhibition of its own. “We will show more of her drawings and notebooks and present the process of how she worked,” says Justin McGuirk, the museum’s chief curator. “This isn’t about a lone genius – Perriand was, above all, a great collaborator.”

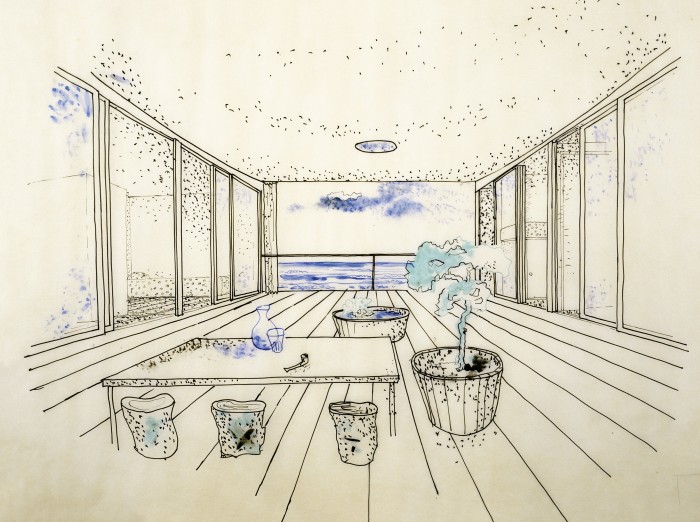

Her most significant work Les Arcs, the French ski resort envisaged by a Perriand-led collective of architects, embodies this collaborative spirit. The project, which opened in 1968 and took shape during the 1970s, showcased many of her skills – not only as a visionary but also as an interiors, furniture and landscape designer – and it was she who proposed the resort’s series of sinuous terraces, which would cleave to the mountain in waves, appearing to melt into the landscape. It encapsulated Perriand’s lifelong belief that good design enables one to live a better life and should be available to all. “All her ideas about life, design and living came together at Les Arcs,” McGuirk says. “As a resort, it was able to cater to mass tourism, but this was mass tourism of a high-minded sort, offering a certain lifestyle and access to sport and nature (always very important to her) that was available to all.”

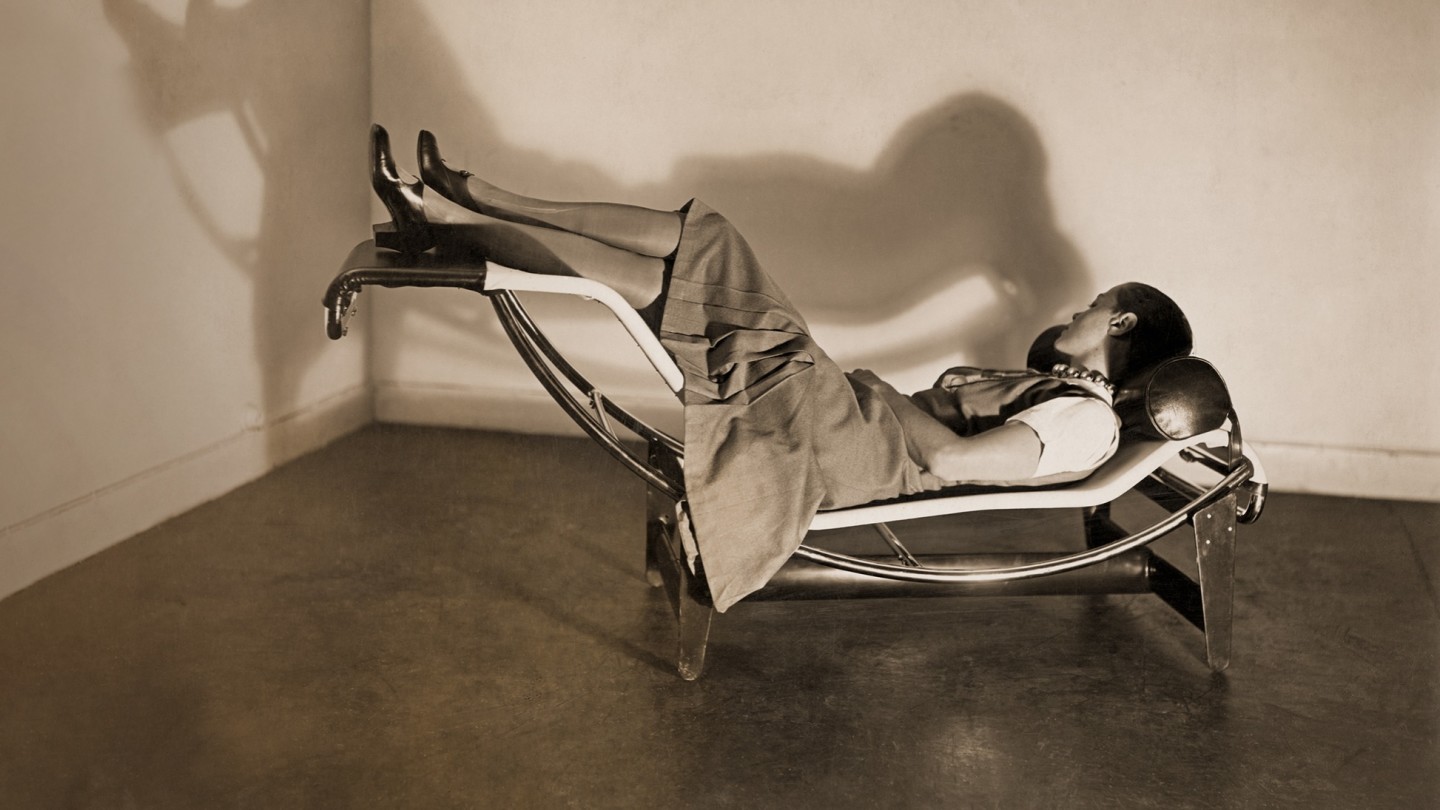

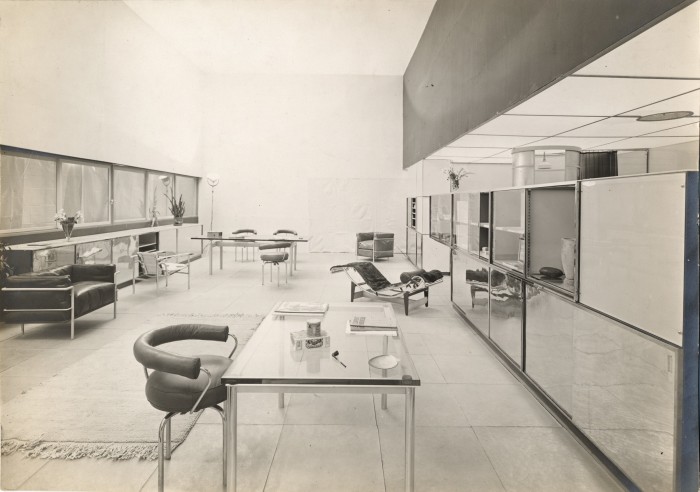

Despite all this, Perriand’s career was long overshadowed by the renown of her male peers. Le Corbusier, in particular, is often credited as the sole creator of pieces that were collaborative – it was Perriand, for instance, who designed the compact modular kitchens for his groundbreaking Unité d’Habitation housing development in Marseille. Three of the most important chairs to come out of Corbusier’s studio during Perriand’s time there – the Grand Confort (a modernist take on the traditional club chair), the Basculante (light and movable, inspired by military campaign chairs), and the Chaise Longue (one for real relaxation) – were for many years attributed to Le Corbusier alone, but while he had dictated the overall parameters (they had, above all, to be modernist), it was she who was tasked with materialising his ideas and who came up with the precise designs.

Now that Perriand is increasingly recognised as a formidable designer in her own right, her work attracts attention from major collectors – French art dealer François Laffanour’s newly released book Living with Charlotte Perriand, for example, shares his experiences with other collectors. Her original designs fetch huge sums on the international market. A one-off Eventail table designed in the 1970s for Perriand’s chalet was given an estimate of €700,000 to €1m in a recent Sotheby’s sale, while an understated wooden dining table sold for £52,920 at Phillips last November – ironic, perhaps, for somebody who so wanted good design to be democratic. That said, accessible re-editions are now produced by the Italian furniture brand Cassina: from the Tokyo chaise longue (1940) – which Perriand conceived during her time in Japan, reimagining the earlier Corbusier studio LC4 design in bamboo – to Nuage (1952/1956), her famous modular bookcase that could be arranged in different combinations. Her furniture was everything that the dark, heavy, bourgeois French designs of the time were not – light, often made using industrialised processes, colourful and, where appropriate, modular.

Laure Adler, author of the book Charlotte Perriand (Livres d’Art), says Perriand's work adhered to fundamental values: “Everything Perriand created was the result of an artistic impulse backed by technical research of high precision,” she explains. “It is perhaps this alliance of the material and the spiritual that we call grace.”

Perriand is far from being alone among the female designers whose recognition has long been overdue. The one-time gallerist Libby Sellers’ book Women Design is filled with similar stories – and the great Eileen Gray (1878-1976) is one of the most distinguished. Sellers tells the unsettling story of how Le Corbusier was allegedly so outraged that Gray’s architectural masterpiece – the modernist E-1027 house, completed in 1929 on the Côte d’Azur – had been designed by a woman that he not only defaced its walls but then built a cabana of his own next door so he could keep an eye on it.

UK-based Aram now reproduces many of Gray’s furniture designs – its owner Zeev Aram recalls being so taken by a selection of her drawings that he saw at a small exhibition at London’s Heinz Gallery in 1973 that he was compelled to track down their source. He met Gray’s niece, the artist Prunella Clough, and made a pact to reintroduce several designs for the first time in many years. Today, they are sought-after classics (is there a sofa more satisfying than her Lota design?), while Gray’s glass-and-tubular steel E-1027 side table and Bibendum chair are some of the most copied designs in the world.

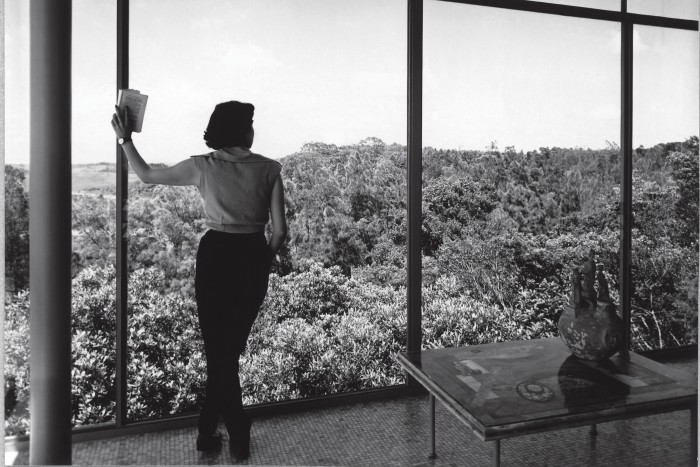

Nina Yashar, who runs the Nilufar gallery in Milan, is a champion of several designers whose work is still too little known. Lina Bo Bardi (1914-1992) was Italian‑born and trained, and moved to Brazil in 1946. She soon began producing extraordinary work that combined a certain intellectual modernism with rich cultural influences from the country that inspired her. Yashar says she’s been obsessed with Bo Bardi since seeing her work in person some six years ago on a trip to Brazil. “I was particularly intrigued by the Concrete and Glass House she created for herself and her husband, in which she allowed the antiques to have a conversation with modern pieces as well as her own designs,” she explains. “It all created an atmosphere of great timelessness that I related to.” In 2018, Yashar produced what she calls “the gallery’s most important exhibition for many years” featuring original Bo Bardi designs. The pieces the gallery sells are rare, and hence expensive, but Etel, a Milanese gallery specialising in Brazilian work, offers re‑editions for those in search of more accessible Bo Bardi works.

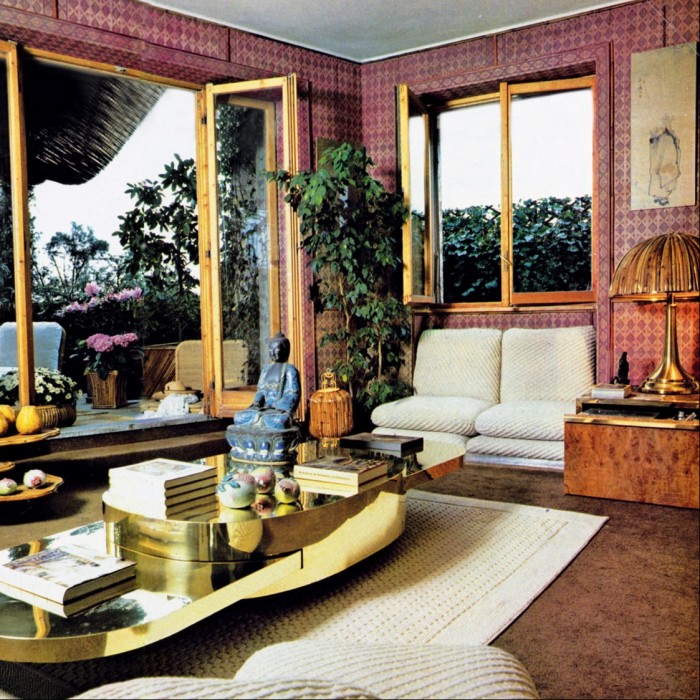

The work of another Italian designer, Gabriella Crespi (1922-2017), has also undergone something of a renaissance. Milan’s Dimore gallery has reissued several of her table and lamp designs created between 1970 and 1980. Crespi was an alluring and glamorous figure born into a distinguished dynasty, who married a member of the family that owned Corriere della Sera newspaper. She worked a great deal in bronze and other metal, and a pair of her low brass-clad Scultura tables recently sold at Phillips for £74,340. Sophisticated glamour most accurately describes her style, and her best-known pieces are her shiny bronze tables and lamps conceived in stainless steel and Plexiglas. Yashar’s Nilufar gallery sells original pieces.

French-Swedish artist Ingrid Donat is a contemporary powerhouse whose work is renowned within design circles but remains little-known given that most of her commissions come from private clients for whom she creates extraordinary interiors, designing everything from the wall finishes to lamps. And yet today she commands very high prices at auction (her Commode Galuchat sold at Phillips for $275,200). Many of her furniture pieces are one-offs, while others come in strict limited editions of eight. Her son Julien Lombrail is a co-founder of Carpenters Workshop Gallery, which is the sole distributor of her work. Donat began her career as a sculptor, and her Buffet Klimt Cinq Portes (2017), a bronze cabinet inspired by Gustav Klimt, perfectly illustrates her aesthetic, which combines great strength and simplicity, influenced by the tribal markings of Africa.

American architect, artist and designer Johanna Grawunder is another talent represented by Carpenters Workshop Gallery. Grawunder is best known for her light installations (she uses fluorescent tubing to create chandeliers and gives them names such as No Whining on the Yacht), but also produces remarkable tables and works for private commission. She honed her skills with Ettore Sottsass for some 16 years but later branched out on her own, first appearing at the Milan Furniture Fair in 1995.“I used light in a way that hadn’t been done before,” she says. “There was a lot of neon and Plexiglas and fibreglass. It was very in-your-face, not what you would call good taste.”

Grawunder’s experiences of high school are perhaps telling of why so many women wait so long for recognition. At 13, she wanted to study draughtsmanship. The subject was deemed suitable at the time for boys only and she was only able to persuade the headmaster that she could take her chosen subject on condition that she would study “sewing” as well. But Grawunder’s story is also a positive one. She is one of the increasing number of female creatives who are putting their heads above the parapet and creating work that demands attention – regardless of gender.

Comments