Aboriginal art

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It’s a pivotal time for Australian Aboriginal art. In Australia, three major prizes restricted to indigenous artists have recently been awarded and have garnered both publicity and comment; in London, Australia is poised to open at the Royal Academy with more than a quarter of its 209 works devoted to Aboriginal art; Bordeaux’s Musée d’Aquitaine opens Vivid Memories: An Aboriginal Art History on October 16; and in Venice, billionaire Luciano Benetton’s new global art mega-project, Imago Mundi, a collateral event to this year’s Biennale, has just opened, presenting more than 1,000 works from contemporary artists in Australia, India, Japan, South Korea and the US. All of the Australian works are Aboriginal.

Yet in market terms things have not been rosy. In 2007 there was an annual Aboriginal art turnover of more than A$200m and an auction take of just under A$24m. But by 2011 those figures had halved and, unlike the international auction scene in London and New York, which has largely recovered, investment in indigenous art remains in the doldrums.

Perhaps a contributing factor is a question about the nature and direction of Aboriginal art. Two distinct strands have evolved, as shown in the results of the three national awards. The Raka Award in Melbourne rewarded the very traditional ochre-painting artist Mabel Juli, from the Gija tribe in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia. There, in the 1980s, the great Rover Thomas invented an artistic style that represented the great open spaces of the Kimberley landscape balanced by subtly different coloured patches that stood for hills, boundaries, legends and, in colonial times, massacres. Juli has taken that style and run with it, illustrating a tale about the man who tried to court his mother-in-law and was exiled to become the moon as an eternal punishment – but minimising the detail even further.

The other two indigenous art awards – arguably more influential for being the oldest (the 30-year-old National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, or NATSIAAs) and the richest (the A$50,000 Western Australian Indigenous Art Awards) respectively, came up with hybrid works as winners. In Darwin, the NATSIAAs favoured a majestic, metre-long, blown-glass work by the Adelaide-born, Canberra-based Jenni Kemarre Martiniello. Canberra is a long way from her ancestral lands in the Central Desert but Martiniello had brought with her the idea of a fish-trap woven from reeds, and sought to recreate this in the Canberra Glassworks with the necessary collaboration of seven non-indigenous colleagues. In that sense, it was a wholly non-indigenous production but Martiniello’s wholly indigenous aim was “to pay tribute to the survival of the oldest living weaving practices in the world”.

In Perth, the Western Australian Award judges went across the continent to the Torres Strait to find their winner. Brian Robinson, like many islanders, came to Cairns on the mainland; he learnt to make spectacular prints, became a curator at the Regional Gallery and can now weave his island lore into any number of forms. His two multimedia works involved printing, wood, plastic, steel, synthetic polymer paint, feathers, plant fibre and shell; one covered 3.5m of ceiling.

The judges noted that the “work reveals images portrayed in the great tradition of the Renaissance frescoes that have been recast with traditional characters from the Torres Strait Islands. Aspects of the stories of Ulysses are brought to life in a frenzied ocean … da Vinci’s flying machines are embodied in the paper planes that attempt to escape from their two-dimensional counterparts on the surface. His ancestral beings wear masks through which lightning comes as the conduit between men and gods, and there are multiple symbols of good and evil.”

All this cultural amalgamation was too much for one of Australia’s most important writers on indigenous art, Nicolas Rothwell. In The Australian newspaper he fulminated against the “worked and fashioned objects [that] are in vogue: carved figurines, soft sculptures, decorated bags and ceramic pieces. There are also woven butterflies, pots and dilly-bags, bush-turkey and cockatoo feather baskets – a pattern suggesting a retreat from painted work as the gold standard for presentation of indigenous cultural themes.”

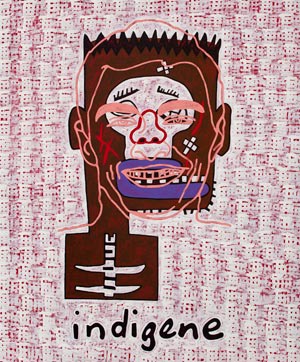

Rothwell also doubted the value of placing “traditional” works in the same exhibitions or competitions as urban or “Blak” art, as it’s sometimes called. “They share a common well-spring … yet they are like apples and oranges, incommensurate,” he wrote.

This is the standpoint taken by Kathleen Soriano, the Royal Academy’s director of exhibitions, who has curated the Australia show with advice from Australia’s National Gallery chiefs. She will open this exhibition with 40 traditional works, while a much smaller number of urban works will appear chronologically among the contemporary Australian art. She told me that it was clear to her that the Blak works’ origins in western art set them apart from the traditional works. Indeed, urban artists such as Tracey Moffatt, Christian Thompson and Gordon Bennett – all with international careers – prefer not to be labelled “Aboriginal artists” any longer, but simply artists who identify as Aboriginal.

When in the 1990s the expat Australian critic Robert Hughes hailed Aboriginal art as “the last great art movement of the 20th century”, he was not writing about this urban art, but about its origins. Surviving the harsh climate of Australia for 50,000 years required enormous discipline and population control. Moral precepts became entwined with creation myths and the “Dreamtime” – the belief system of Aboriginal Australia. Ceremonies requiring body painting, ground paintings and symbolic patterned objects brought together song, dance and art in mnemonic forms to reinforce learning.

With the arrival of the white invader, such knowledge was held tight within each tribe to maintain its identity. In the 1970s, however, as government policies saw tribes herded into settlements, tribal leaders began to recognise the need to reveal some of the complexity of their hidden culture. School walls or old building boards were painted, sometimes with material later judged too secret to be seen by the uninitiated. The style of desert dotting was developed to conceal the sacred.

Over time, different styles of painting emerged as each community – invariably given an art centre and art adviser by the government – reflected its own tribal stories and forms on canvas, paper or wood. Those advisers have undoubtedly played a role in supplying outside ideas, paints and materials. But, fundamentally, artists are putting down how they see their world. Viewers, especially overseas curators, like to see abstraction in the land- and mythscapes of an artist such as Emily Kngwarreye, who emerged in 1988 from a former cattle station named Utopia, or abstract expressionism in the fiercely gestural works of Anangu artists from the great blank spaces west of Uluru.

What of the colour-field thinking in Rover Thomas’s Kimberley works? Famously, Thomas turned the tables when he spotted a Rothko in the Canberra Gallery and demanded: “Who’s this white fella who paints like me?”

Meanwhile, urban Blak art seems to go from strength to strength, with frequent showings in the US, sole Australian representation at the recent National Gallery of Canada show entitled Sakahàn (which brought together 150 works of recent indigenous art by artists from 16 countries) and a show currently in Brisbane’s Queensland Art Gallery representing indigenous people “as we are now”. Their point, it seems, is to underline the fact that an artist (or curator) doesn’t cease to be indigenous when they leave their country.

——————————————-

For links to exhibition and awards, go to www.ft.com/arts

Comments