Education policy cannot be business-as-usual after Covid

Simply sign up to the Education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is a philanthropist and the founding chair of Central Square Foundation of India

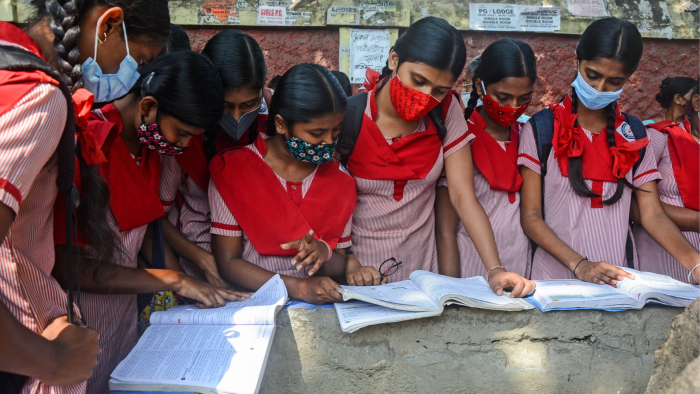

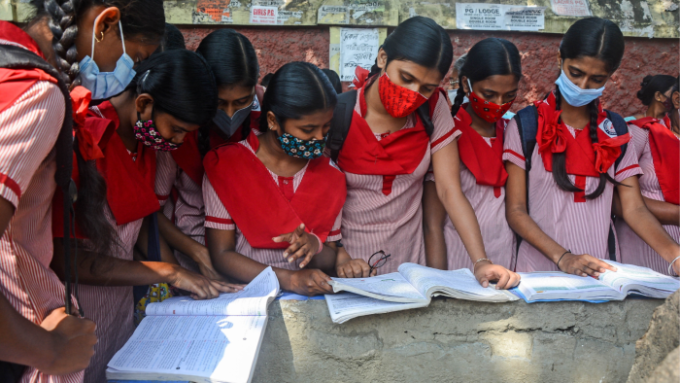

In low- and middle-income countries, more than half of all children cannot read and understand a simple story after five years of schooling. This only worsened when the Covid pandemic led to school closures. Not only did children lose out on in-person learning, they also forgot what they had learnt in the previous year.

In India, for example, more than 90 per cent of those in grades 2-6 lost at least one specific language ability in 2021, on average, compared with the start of the coronavirus outbreak. Similarly, more than four-fifths lost at least one specific mathematical ability. Across developing countries, this “learning poverty” has increased by almost a third since the onset of the pandemic. That risks a massive reduction in these children’s potential lifetime earnings.

To enable them to focus on learning recovery, we must be aware of their social and emotional needs — especially the needs of children from underprivileged backgrounds, as the pandemic continues to disrupt their lives.

Reading with meaning and solving basic mathematical problems by the end of class 3 (age 8) are foundational skills in which every child must be proficient. People assume that secondary school leaving exams can make or break a student’s life, but they will only succeed if they first acquire the critical reading, writing and numeracy skills in the early grades.

There is a growing realisation that business as usual will not suffice in a post-pandemic world. Policymakers are responding.

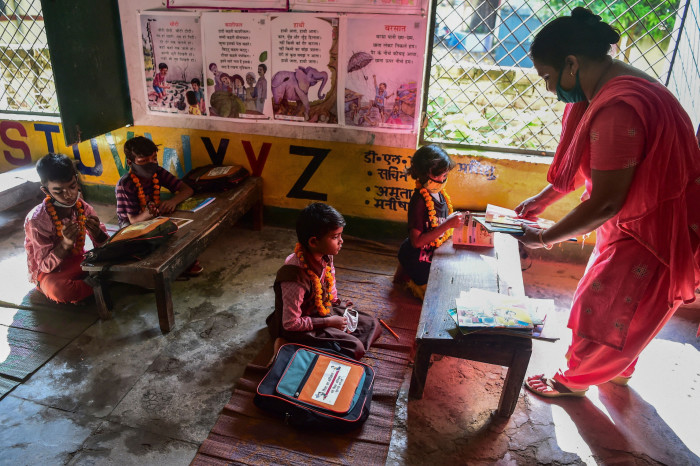

India’s 2020 National Education Policy places the highest priority on foundational learning and stresses the need for urgency. The education ministry launched a nationwide mission, NIPUN Bharat (National Initiative for Proficiency in Reading with Understanding and Numeracy), which aims to ensure that all children acquire these foundational skills by 2026-27.

India’s efforts to identify learning gaps and address them in mission mode is inspiring. It has adopted a systemic approach that prioritises the following five elements.

Goal setting. We need to build a common understanding of tightly defined learning goals for grades 1-3. Uttar Pradesh, for instance, has said every child in grade 2 should be able to solve addition and subtraction problems. Defining what children should know and be able to do in every grade will drive learning in a structured manner. That makes it easier to monitor, holds stakeholders accountable, and quantifies progress. India’s prime minister Narendra Modi has lent his support to goals such as Oral Reading Fluency — the number of words a child can read per minute with fluency, accuracy, and meaning.

Pedagogical approach and resources. To ensure uniform and high standards in every classroom, we need to build a strong suite of teaching and learning resources and teacher support systems. These include materials for students, such as workbooks and step-by-step lesson plans for teachers, along with ongoing coaching and support. Such a structured pedagogy approach can improve learning outcomes at scale, as demonstrated by programs like Tusome in Kenya and Room to Read in India.

Learning at home using Edtech. With schools closed during the pandemic, governments, teachers and parents alike turned to educational technology to continue learning. We must not lose that momentum. Edtech has the potential to improve outcomes by allowing children to learn at their own level and pace. We need to make better use of it at home to help children learn and practise what is being taught in the classroom — an approach adopted by Rocket Learning, an Indian non-profit.

Monitoring and evaluation. Constant tracking against foundational literacy and numeracy goals is essential to assess progress and adopt course-correcting measures. Uttar Pradesh, for instance, uses many technological tools for monitoring classroom observations and teacher mentoring. It presents multiple metrics in a user-friendly and colour-coded single page report that can be easily interpreted by administrators.

Student assessments. India runs the world’s largest sample-based large-scale assessment: the National Achievement Survey. Such systems provide a useful snapshot of how the education system is faring, indicating what is working and what needs to be improved. Classroom assessments need to be “low-stakes”: not to pass or fail students, nor to measure teacher performance, but rather to help tweak teachers’ approaches for improved outcomes. We must continue to support and empower teachers, given many factors are beyond their control in the classroom.

Any national effort must also extend to private schools. Nearly half of India’s children study in private schools, most of which cater to children from low-income communities. But these schools have no external exams until grades 10 and 12, which makes it difficult for parents to understand how their children are performing on learning outcomes. India’s National Education Policy calls for assessments for all children at the end of grades 3, 5 and 8 — much like Australia’s National Assessment Program. These exams help empower parents to make informed school choices.

Children in primary grades today will join the workforce by 2035. If India and other developing countries prioritise better educational outcomes, we will be able to reap the demographic dividend for decades to come.

Comments