Commercial property investors descend on booming Bucharest

Simply sign up to the Property sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Grozavesti — until recently an uninspiring district of student flats and old industrial buildings — now hums with the sound of construction. The arrival of an enormous suspension bridge connecting the district with the city centre has brought diggers and cranes to the once sleepy neighbourhood. The regeneration is one sign of the recovering property market in Europe’s quickest-growing economy.

Grozavesti’s new office buildings, in the west of the city, are being pitched at the IT and shared-services companies that form the fastest-growing sector in Romania. The largest among these projects is The Bridge, a €100m, two-phase 57,000 square metre development on the site of an old bread factory.

The first phase is already fully leased to Erste Bank and IBM, and will be completed in October, according to Geo Margescu, chief executive of Forte Partners, the partnership of local developers behind the project. He says the partners bought up land sites like these during the financial crisis and joined forces in 2013. “Now we want to grow our portfolio in the city,” he adds.

The transformation illustrates a new chapter in the Romanian capital’s property investment story. After a collapse in investment volumes following the financial crisis of 2008, this year will be the market’s best performance since the property crash, according to Colliers International Romania, which recorded €400m in transactions by the end of August and is predicting €1bn by the end of the year.

This citywide revival is reshaping the map of the city’s premium office space. The pre-crash boom years saw frenzied construction of soaring glass towers in the north of the city, transforming the grey Ceausescu-era skyline of the EU’s sixth-largest capital by population and becoming a visible symbol of Romania’s rapid modernisation. But prime office development in northern neighbourhoods such as Floreasca-Barbu Vacarescu has led to transport congestion, while stalled construction in the early post-crisis years has pushed up prices.

“Floreasca was a perfect choice for office development because it had good transport links, lots of available development land and was cornered by high-end residential areas like Primavera,” says Sinziana Oprea, associate director at Colliers International Romania. “Even though it is quite crowded now, it is still popular.”

But Floreasca’s saturation, combined with the expansion of Romania’s economy, have opened up investment possibilities elsewhere in the capital. “Northern Bucharest is more crowded, there are fewer plots and the sites are smaller,” Mr Margescu says from inside the Bridge construction site, where workers are laying the floors of the building.

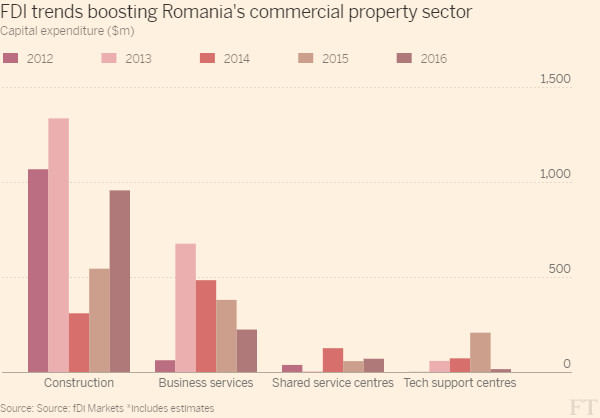

“The new bridge and the transport infrastructure in Grozavesti have created important connections with the city centre,” he adds. Office demand in new parts of the city has been powered by the steady growth of the IT and shared services sector — such as the outsourcing of back-office functions like customer support, accounting, HR and IT.

Prime office yields of 7.5 per cent — 2.25 percentage points higher than in more established regional markets like Warsaw — have caught the attention of foreign investors.

Nepi, the Johannesburg-listed investment company, has had a presence here for several years and in 2017 announced more than $50m worth of investments. It has been joined by others such as Skanska Construction Romania, a subsidiary of the Swedish company, which this year announced €74.8m of investments in two Bucharest office construction projects.

The company says Romania’s strong economic growth, increasing demand for high-quality offices and attractive yields were the factors behind its decision to invest. “These all serve as a guarantee of a good deal and long-term profitability in Bucharest,” says Adrian Karczewicz, head of central and eastern Europe divestments at Skanska’s regional commercial development office.

The average vacancy rate in the prime office sector is 12 per cent, according to Colliers International, although that conceals wide variation by district, with greater demand for premium space in Floreasca-Barbu Vacarescu.

Both overseas and local investors are advancing quickly to second-phase developments in order to meet demand. Colliers forecasts the city will increase its premium office space by 140,000 sq m by the end of 2017. That trend is visible in places like Grozavesti, where a rival office construction site is rising across the street from The Bridge.

Try the FT’s dynamic country data dashboard

Romania: latest news and live data

See the latest Romanian business and finance news, alongside economists’ forecasts for GDP, inflation, current account and the leu-euro exchange rate — all in one place

There are some clouds on Bucharest’s horizon, however. The city’s transport system is at full capacity in many office neighbourhoods, increasing commute times for workers and decreasing productivity. Investors were also startled by the prospect of unexpected changes to taxes and regulations for large companies, which were announced in July, although they were quickly shelved following a corporate backlash.

Even so, the discussions sent jitters throughout the Bucharest office market. “Our biggest concern is the visibility of legislation. We need to be able to project certainty into the future,” says Mr Margescu.

Ms Oprea adds that frequent legal changes affecting important sectors such as IT also unsettle the office market.

The uncertain regulatory environment does not help, she says, and the property sector has some way to go to return to pre-crisis investment volumes. But Bucharest’s office market recovery is well underway.

Comments