Questions raised over Asian ETFs in unyielding market

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Bond exchange traded funds (ETFs) are known for their aggressive expansion.

Offering lower fees and better trading than traditional counterparts, bond ETFs — which passively follow indices of bonds and trade on exchanges — are quick to outperform and steal market share from traditional bond funds.

In the US, Europe and Australia, bond ETFs have expanded, making deep incursions into traditional bond fund territory. But Asian financial centres — such as Hong Kong, Singapore and Seoul — have resisted the ETF industry’s advance.

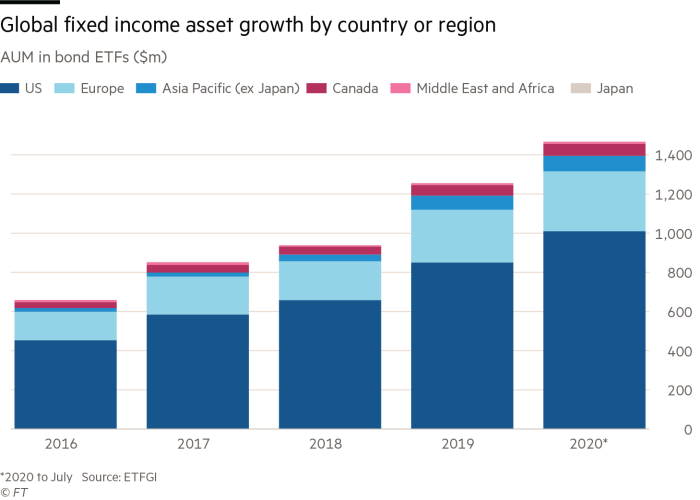

In the US, bond ETFs are a dominant force, having captured a stupendous $1tn in investor money as of July 2020, data from consultancy ETFGI indicates. Even the Federal Reserve uses them. Bond ETFs are also strong in Europe, where they store $304bn — a number that has doubled since 2016.

In Asia, however, bond ETFs are very small and rarely used. In Hong Kong and Singapore, bond ETFs held $5bn and $1.3bn respectively at the end of August, making up less than 1 per cent of each country’s bond fund market, Ultumus data indicates.

According to Aleksey Mironenko, global head of investment solutions at The Capital Company, a Hong Kong financial adviser, a big reason that Asian bond ETFs struggle is that deep-pocketed institutional investors — such as hedge funds and sovereign wealth funds — prefer using US and European ETFs. This is because they are cheaper and easier to trade than their Asian counterparts.

“There’s no public record of how much Asian money is invested in the London ETF market. But we know that it is quite large,” he says.

Private investors have also given bond ETFs a cold shoulder.

In many Asian countries, private investors prefer investments that give them a chance to get rich quickly. Popular examples of these include warrants in Hong Kong, penny stocks in China, and bitcoin in South Korea (prior to its being banned).

According to Nathan Oh, a portfolio manager at Mirae Asset, a Seoul-based ETF provider, the lottery mentality has been fuelled by worse job prospects and unaffordable housing. Bond ETFs, which typically buy safe government debt and offer small returns, do not offer the chance for aggressive wealth building.

Mr Oh says: “Average income is low compared to rising consumer prices and housing prices in [South] Korea, especially in Seoul . . . and the unemployment rate for people aged 20—30 is high.”

Rich South Koreans, meanwhile, rarely use bond ETFs either, he adds, as they “tend to invest in properties — not stocks or bonds”.

But the most crucial obstacle for bond ETFs in the region is the way that bankers — the primary gatekeepers of the region’s treasure — get paid.

In Hong Kong and Singapore, bankers demand a quid-pro-quo from fund managers, including those running ETFs.

If they put a client’s money into a fund, they expect to be paid a commission. If fund managers refuse, they won’t send them clients.

But low-fee bond ETFs rarely pay high commissions. This puts ETFs at a steep disadvantage when trying to win over the banks.

“ETFs that are not paying fees or commissions to [banks] have usually been deprioritised,” explains Rebecca Chua, a founder of Premia Partners, a Hong Kong ETF issuer.

The result is that many private investors “do not even know about ETFs”, unless ETF issuers spend heavily on marketing, she adds.

The effect of commissions also shows up in the fate of Vanguard — the second largest ETF provider. While Vanguard has surged to become the largest ETF provider in Australia, where commissions are banned, the group closed its offices in Singapore and Hong Kong, where commissions are the norm.

What is more, the commission system looks here to stay.

Both Singapore and Hong Kong conducted reviews recently and concluded the same thing: commissions are fine so long as they are disclosed.

In both countries, financial services like private banking are big employers, and banning commissions could result in lower profits and job losses, analysts note.

“It’s quite a bit of employment, it’s quite a bit of tax revenue in these two small markets,” Mr Mironenko says. “I do not see any movement [towards banning commissions].” With the odds stacked against them, questions have been raised about whether Asian bond ETFs have any hope at all.

Another question being asked is whether the region will remain a bastion of traditional bond funds.

If bond ETFs do fail, asset managers may breathe a sigh of relief. Thanks largely to the rise of ETFs, asset managers’ profit margins globally are under sustained pressure. But margins in Asia are much higher than those in Europe and the US, an analysis from consultancy McKinsey has found.

The failure of bond ETFs might give asset managers a much-needed break.

Comments