In the Highlands, a lonely bothy begins a new life

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

One day in 1942, Margaret MacDonald and her brother-in-law Sandy packed their things and closed the door on their little stone-walled cottage for the final time. The village of Peanmeanach had been inhabited for hundreds of years, by generations of crofters and by Vikings before them, but the world had moved on and gradually the inhabitants had drifted away. Margaret and Sandy were the last to go.

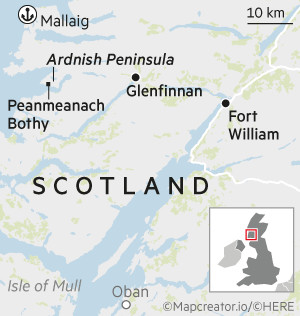

Peanmeanach sits beside the gently curving shoreline at the far end of the Ardnish peninsula — 3,500 acres of mountains, lochs, heather and herds of deer, undisturbed by a single road. Margaret had been the teacher at the village school, with 28 children on her roll at one point, while her husband John ran the local post office from their house.

With no shops on the peninsula, food arrived by a steamer which moored offshore; villagers would row out to collect oatmeal, flour and maize. Nellie, one of Margaret’s five children, grew rhubarb and blackberries and milked their nine cows. There were ceilidhs, visits to nearby beaches and a strong sense of community but life had changed little in hundreds of years. Water was from a well, clothes were still washed in the stream. Margaret’s daughter Mary died at 22; her son Hugh Angus succumbed to appendicitis aged just 13.

By the 1920s, fishing was in decline and other jobs had dwindled. By 1932 there were no children left in the school for Margaret to teach; soon there was no post to deliver either. When wartime rationing cut paraffin supplies and left villagers with just one candle per week, the long winter nights must have been bleak, the pull of the towns and cities impossible to ignore.

Nellie returned briefly in 1998, to look one last time at her former house and the ruins of the school where her mother had taught. Did she regret leaving, asked one of those accompanying her. Apparently the 85-year-old replied simply and emphatically: “No.”

Eight decades after Margaret and Sandy moved out, we caught sight of the house they left, the house Nellie was born and grew up in. Three friends and I had been walking for a couple of hours, laden with heavy rucksacks full of food, firewood and, let’s be honest, wine. We had crossed a little hump-back footbridge over the railway that marks the northern edge of Ardnish, where the peninsula backs on to the mainland. Then we had balanced across a bridge made of two old planks to reach the only footpath, an ancient trail heading south over the mountains to Peanmeanach.

A map-reading mishap left us going in circles, then scrambling up a steep muddy hillside, sweating among the bracken and with ticks clinging to our socks. Now, at last, we emerged onto the open rocky uplands to be rewarded with a breeze and a view to the sea, and there in the distance, the MacDonalds’ house, with its neat chimneys at either end, the stones of one gable shining in the afternoon sun. It was to be our home for the next two nights and it looked utterly blissful.

For a transformation has taken place in the years of Peanmeanch’s abandonment. Not so much in the place itself, though the nettles have grown up and the deer have become more brazen in their evening strolls between the ruined houses, but in the tastes and desires of the urban world beyond this sequestered peninsula. The yearning for wilderness and the urge to disconnect are being felt ever more widely. What was a place of darkness and deprivation now seems somewhere to escape to, not from.

“On the website I try to put people off,” says Peter Stewart-Sandeman, owner of Ardnish Estate, who now runs the old schoolmistress’s house as a bothy, providing simple accommodation for visitors. “But the things you’d think were the biggest disadvantages — no electricity, no running water, the fact you can only get there on foot or by boat — have now become the real pulling power.”

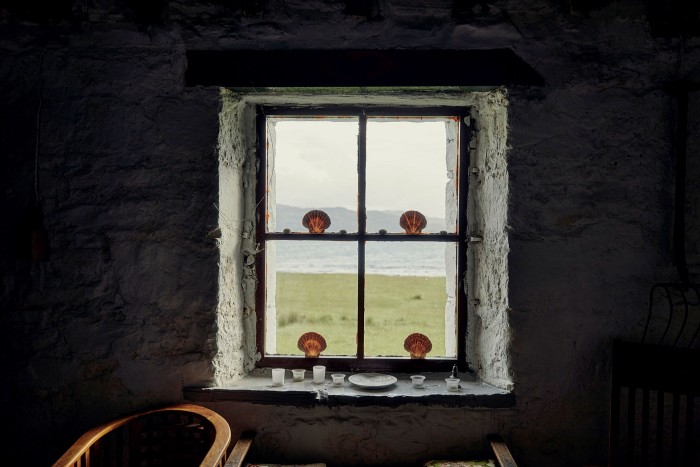

We pushed open the door to find a cottage which was undeniably basic but pretty and welcoming nonetheless: a living room and kitchen on the ground floor, two spartan bedrooms with camp beds upstairs. Instead of a toilet there was a spade. The rough stone walls were whitewashed, a rocking chair sat by the wood burning stove, scallop shells propped against the window panes were illuminated in the sunlight. We built the fire, using driftwood left by the previous guests, then ran down to the sand to swim.

For 20 years after the MacDonalds left, their house was used only by cows and eventually the roof fell in. In the 1970s, it was restored and opened as a bothy, becoming one of about 100 remote buildings maintained by the Mountain Bothies Association “for the use and benefit of all who love wild and lonely places”. Most are in Scotland, a few in northern England and Wales; many are former shepherds’ huts or farm buildings; all are are free to use and can’t be booked, the doors simply left unlocked for passing hikers.

Inside they might be almost empty except for a fireplace and raised wooden platform on which to unroll your sleeping bag, but they hold a sort of semi-religious significance for lovers of the outdoors in Britain. Though you might not actually fancy sleeping in one, the existence of bothies embodies the sense that the country’s wild spaces are there for everyone and stand apart from the commercial world. And for those trapped at their desks in distant cities, there is something comforting in knowing these places of refuge remain open and welcoming, unchanged by the passing years, defiant against the rain and winds. The only other buildings in the UK left open in the same way are churches.

Bothies also promise communion: those arriving have no idea who they will meet and spend the evening by the fire with. When else does that happen? The hope is that a shared love of the outdoors, and the help of a few drams, will forge new friendships.

In recent years, however, harsh realities have come crashing in on the cosy bothy dream. Traditionally the huts’ locations were passed between like-minded enthusiasts by word of mouth, but then came the internet and social media and the details began leaking to a wider audience. In 2009 the MBA took the controversial decision to list the locations online, then 2017 brought the publication of the first “complete guide to Scotland’s bothies and how to reach them”, The Scottish Bothy Bible. Bitterly resented by some of the faithful, it was wildly popular and spawned several follow-ups. What had been a niche pursuit found itself the subject of listicles in newspaper supplements and thousands of Instagram posts.

Formerly lonely bothies became busier; reports of vandalism and antisocial behaviour grew. In 2019 police in southern Scotland launched a “Bothy Watch” scheme after warning the huts had begun to attract “a different type of user”.

The pandemic seemed to drive demand still higher and while some came seeking only nature and a mindful escape from confinement, others were looking to party. “Peanmeanach just became too busy, people were using it as somewhere for free stag parties,” says Stewart-Sandeman. At some points there were 20 people staying inside, more camping outside; visitors were chopping living branches from trees to burn, spraying graffiti on the walls. “Who walks for two and a half hours carrying spray cans? The answer is quite a lot of people.”

And so in October 2020, Stewart-Sandeman took the decision to close Peanmeanach and remove it from the MBA’s roster. Interiors were redecorated and furniture brought over by boat to raise the standard of comfort. Then in May last year it was relaunched as a new type of bothy: pre-bookable, paid-for and for exclusive use by one group, though still cheap (£55 per night for up to six) and run on a not-for-profit basis, with all proceeds put towards maintenance. Guests are now sent a code for the padlock a few days before arrival.

Some traditionalists have bemoaned the idea of the “private bothy” but the paradigm could catch on. In June a second bothy, An Cladach on the Isle of Jura, is due to reopen on a similar model, and will now be bookable for £20 per night.

Part of the reason Peanmeanach is in the vanguard of the issues affecting bothies is that, though it looks and feels so remote, it’s actually very accessible. We travelled there entirely by train: leaving London on the Caledonian Sleeper after a day in the office, waking up with the vast open spaces of Rannoch Moor rushing past the windows. At Fort William we changed on to the little branch line to Mallaig (a route also used by the Jacobite steam train, popular with Harry Potter fans thanks to its appearance as the Hogwarts Express). Shortly after midday the train dropped us on the empty platform at Lochailort to begin the five-mile walk to the bothy.

That first evening we sat outside watching the clouds roll over the mountains of Moidart. The views were immense, the cottage cosy, the sea had been surprisingly warm but the main thing was the sense of sudden solitude. Twenty hours after leaving London we were alone in the ruined village, without phone signal or radio, in silence except for the sound of the breaking waves.

Echoes of past lives were all around. To either side were the ruins of a dozen blackhouses, thatched roofs long gone but the craftsmanship of the hand-hewn stone walls, beautifully rounded at the corners, still clear to see. On the edge of the beach was a naust — a hollow dug into the sand by Vikings to shelter a longboat. Wandering nearby I spotted something blue among the sandy pebbles, the threadbare and seaweed-streaked remains of a baseball cap with the just-visible logo of the Mexico City football team Deportivo Cruz Azul, perhaps carried here on the North Atlantic Current. It was like a realisation of all those ubi sunt Anglo Saxon poems, except rather than mourning our isolation we were celebrating it.

The next day we went exploring. Behind the bothy, we walked though an ancient oak forest where wheatears in the branches called back when I whistled. Then we walked west along the coast, passing the old school, then pushing through bracken, stooping occasionally to look at small pink and white orchids. Eventually we clambered down some rocks onto the Singing Sands, perhaps the most perfect beach I’ve ever stood on: pure white sand, a rocky islet in the shallows, and not a soul to share it with. The name comes from the fact the sand makes a squeaking sound when you step on it — a phenomenon apparently caused by grains of sand that are unusually spherical.

Walking back through the shallows to our own bay we had a shock. Rounding some rocks, we heard voices. Though we’d been there barely a day, it was hard not to feel a bit like Robinson Crusoe spotting a footprint. They turned out to be sea-kayakers, a group of at least 10 on a multi-day trip along the coast, mainly Australians working in London. They set up tents along the edge of the beach, a visual reminder that, these days, wilderness and seclusion are prized commodities.

In the morning they had vanished before we got up, perhaps to get ahead of an incoming storm, leaving us alone once more for our final few hours. Before we left I looked at the visitors book and a name caught my eye — Margaret MacQueen, the daughter of Nellie, granddaughter of Margaret MacDonald, had come to stay a few days earlier. “We had an absolutely perfect time in our mother’s old home and birthplace,” she wrote. “We could almost feel their presence all around us.”

Details

Tom Robbins was a guest of Ardnish Estate and the Caledonian Sleeper. Peanmeanach Bothy sleeps six and costs £42 per night on weekdays, £55 per night at weekends. Return tickets from London to Fort William on the Caledonian Sleeper cost from about £205 per person, based on two sharing a cabin

Letter in response to this article:

Bothy with a padlock that charges for a bed, really? / From Nigel Morton, North Berwick, East Lothian, UK

Comments