Chemicals: core to a net zero future

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The chemical industry is an integral part of the global economy. Its products are ubiquitous — used in all sectors from agriculture and construction to consumer goods. Sector revenue of $4.7tn last year represents almost 5 per cent of world gross domestic product. The chemicals sector has also been one of the best stock market performers so far this century.

Yet the industry is also a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions — rivalled only by steel and cement production as the largest industrial source. Estimates from the World Resources Institute suggest chemicals, including petrochemicals, are responsible for 3.6 per cent of global emissions due to energy use in production, plus another 2.2 per cent from the use of fossil fuels as raw materials, especially in plastics, or as a byproduct of chemical processes.

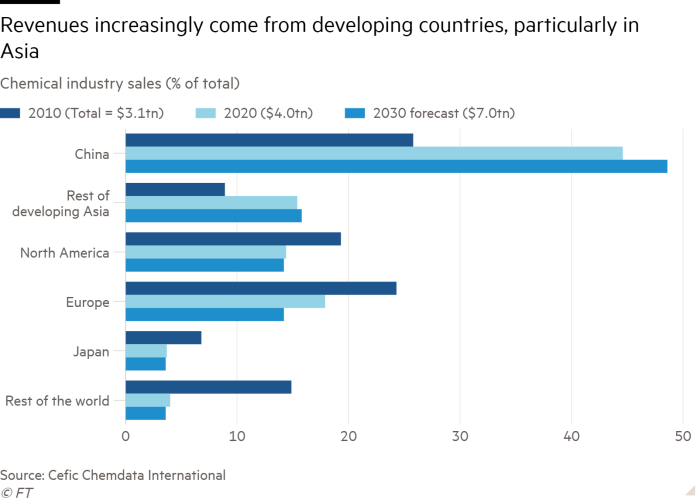

Recent growth has been predominantly in emerging markets, particularly in Asia, including China and India — some of the largest national emitters.

Chemical companies have lobbied against green measures in the past. They have also largely escaped public pressure to change their practices, since they operate in the background, removed from the consumer-facing companies that they supply.

Some progress has been made. Figures from industry body the European Chemical Industry Council show that greenhouse gas emissions from the EU chemical industry fell 54 per cent from 1990 to 2019, even as output rose 47 per cent. Much of this was due to more efficient use of fossil fuels, however. Total energy consumption fell by a fifth over this period and renewable and biofuels accounted for only 0.6 per cent of energy consumption in 2019.

A report published in September suggested a strategy towards a net zero future for chemicals. “Planet Positive Chemicals” from sustainability consultants Systemiq, and the Centre for Global Commons based at the University of Tokyo, outlined radical proposals that could make the industry carbon-negative by 2040 and a carbon sink by mid-century — even while doubling turnover and creating 29mn new jobs.

“The chemical industry underpins every modern economy, but it must change profoundly across its entire value chain to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement,” said Guido Schmidt-Traub, managing partner at Systemiq, in the report. “Importantly, these changes are eminently feasible using proven technologies,” he added.

Some $100nn a year in capital expenditure would be needed over the next 30 years, more than two-and-a-half times the requirement for business-as-usual growth but small in relation to the size of the industry.

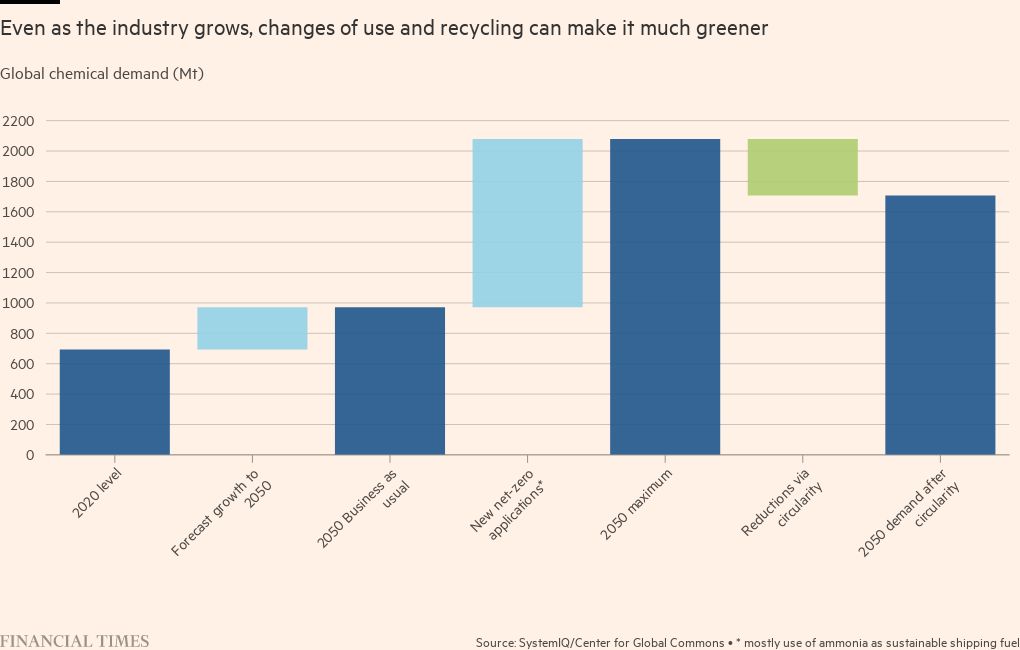

Much of the technology needed is already in place. Increased recycling of plastic, targeted use of fertiliser, and investment in green hydrogen could rapidly reduce emissions. Ammonia can be increasingly used as a sustainable shipping fuel and methanol can be used to create plastic without using fossil sources.

Currently, though, the chemical value chain has low reuse and recycling rates and generates a lot of waste. Roughly 70 per cent of nitrogen input in fertiliser is not taken up by crops and only 9-14 per cent of plastic ever created has been recycled.

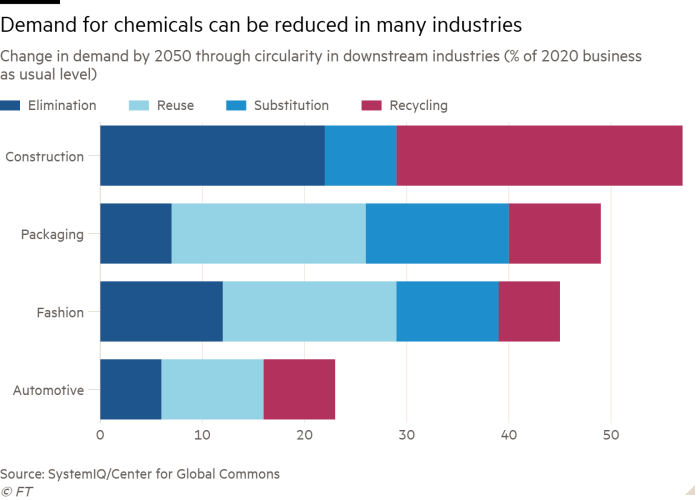

Demand-side “circular economy” approaches of reduction, reuse, substitution and recycling could reduce total chemical demand by as much as 31 per cent by 2050 for non-ammonia chemicals.

The report estimates that 82 per cent of carbon feedstock — raw material for production — can be replaced by renewable alternatives by 2050. Some carbon capture and storage is likely to be needed to reduce process and disposal emissions.

Without these changes, emissions from chemical manufacture could contribute to a rise in global temperatures by as much as 4C above pre-industrial levels, with catastrophic climate consequences.

Yet, the report stresses, given its position as a supplier to other sectors, the chemical industry could be an enabler in the green transition. Either way, it will be at the centre of attempts to decarbonise the world economy.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments