Will the cloud kill the data centre? Jim Chanos thinks so

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Veteran short seller Jim Chanos has a new target in his sight: the humble data centre.

In June, Chanos — who won big bets on the downfall of US energy group Enron and the German payments company Wirecard — announced that his eponymous investment firm is raising several hundred million dollars for a fund that will take short positions in US-listed data centre groups.

He argues that the move towards the cloud, predominantly driven by Big Tech groups such as Microsoft, Amazon and Google, is the “enemy” of bricks-and-mortar real estate investment trusts such as Equinix and Digital Realty.

These players buy large swaths of land, build vast complexes, source major energy contracts and allow companies to lease space in their centres to process their data.

The Big Tech groups, by contrast, utilise their own equipment and process clients’ data for them in the “public cloud”. Dubbed “hyperscalers”, they either store their hardware and server equipment in real estate investment trusts, such as Equinix — or increasingly build their own supersized centres to meet ballooning demand for their services. One Microsoft data centre in Chicago spans 700,000 sq ft, the size of 52 Olympic swimming pools.

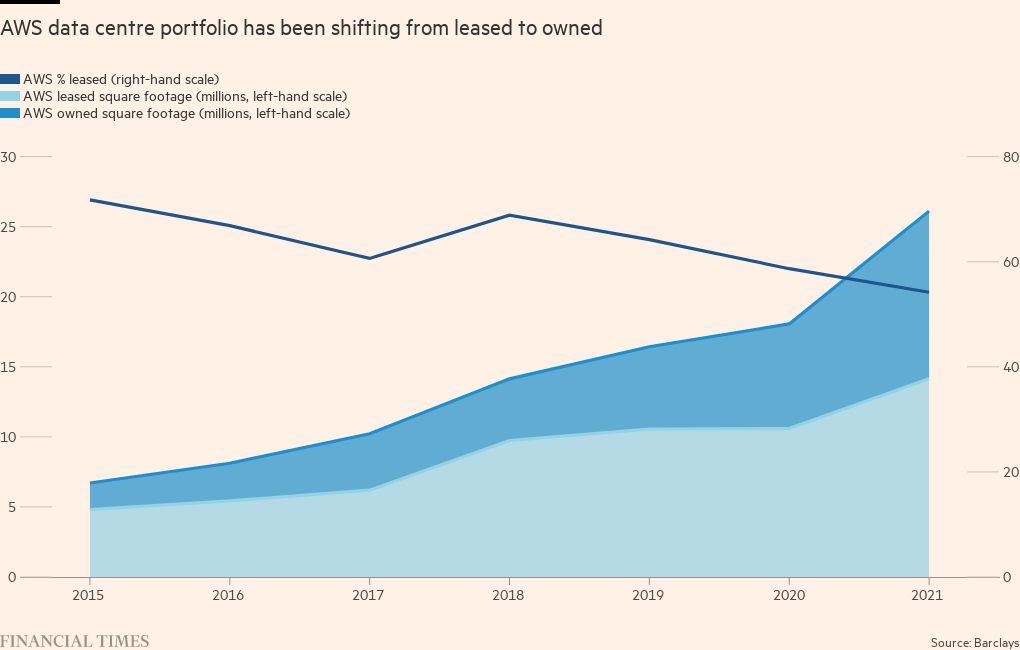

Chanos, who has also been hurt by a longstanding bet against Tesla, believes the tech behemoths, which he says account for around two-thirds of data centre demand, will increasingly move towards building and running their own real estate. He argues they will do this because the technology used by legacy groups is becoming old and redundant and because cash-rich Big Tech groups can build more cheaply. This will render the independent real estate investment trusts redundant.

But other investors argue the data centre and specialist operators have life in them yet. Nathan Luckey, senior managing director of digital infrastructure at Macquarie Asset Management, who has spearheaded several recent investments in data centre assets, said the best companies are those sitting on prime real estate in strategic locations.

“Hyperscalers are looking for trusted partners where they can house more and more compute power,” he argued. “If there is someone who already has land and a property in a market they want to expand into, that’s a very relevant factor.”

Billions of dollars in private equity capital have poured into the industry, with bulls arguing that traditional data centre groups will remain indispensable given their strong position in top locations and expertise in procuring resources such as power, land and labour. They also cite their privileged position as so-called “carrier hotels”, an industry term meaning they connect lots of different businesses.

These groups and their PE cheerleaders are wagering that data demand will continue to grow, and a wide range of customers — from cloud service providers to banks and government departments — will continue to store at least some of their workloads in traditional data centres.

Last year, the world’s biggest private equity firm Blackstone acquired Kansas-headquartered QTS Realty Trust for $10bn while KKR and GI Partners purchased Texas-based CyrusOne for $15bn. Earlier this month, Macquarie bought a significant minority stake in British data centre provider Virtus for an undisclosed sum, betting that Big Tech groups will be forced to lease as they expand into Europe.

Chanos derided these transactions as “rash”, with valuations that were “stretched by any measure”, and predicted a “post-takeover hangover” in a presentation.

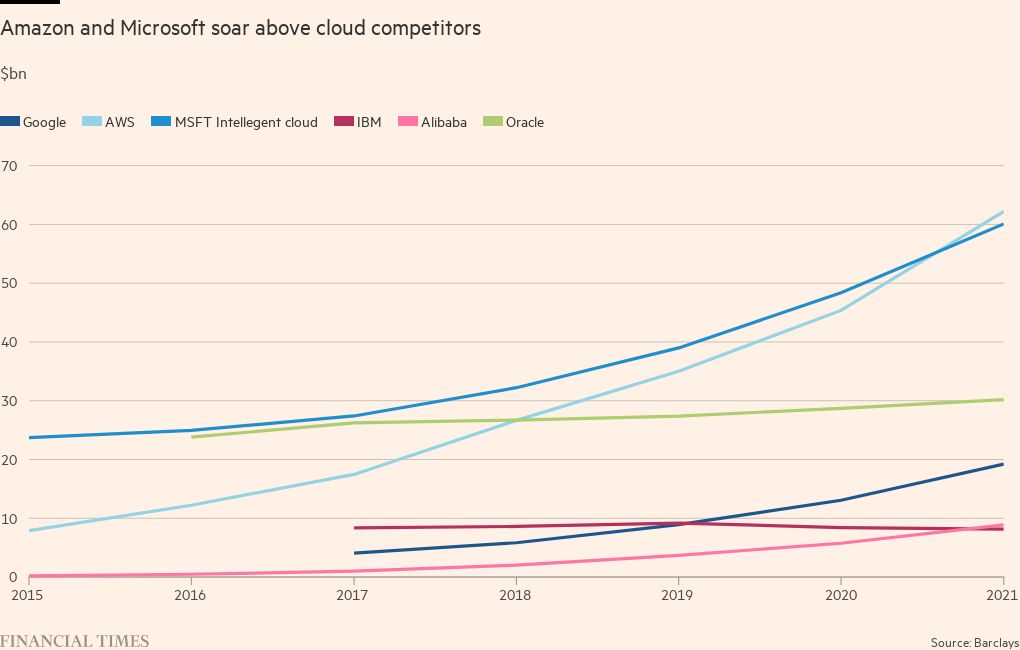

Cloud business has been the engine of growth for groups such as Amazon, Microsoft and Google over the past year. In the first quarter of 2022, Amazon Web Services’ revenue was up 37 per cent year on year to $18.4bn, while revenue at Microsoft’s Azure platform increased by 40 per cent.

“The compute workloads for Google and Meta are just unimaginable,” said Martijn Blanken, chief executive of EXA Infrastructure, which supplies networking infrastructure for the hyperscalers. “It’s a scale game, and there’s no enterprise that can compete with them.”

By contrast, listed US data centre groups have posted healthy — but less impressive — growth. Yet those in the data centre industry argue Chanos’s thesis is dated, given that the same arguments have emerged several times over the past 15 years, including a highly publicised short position taken against Digital Realty by Highfields Capital Management in 2013. Highfields made money, but Digital Realty is still in business.

“There’s a fallacy in the argument that we’re not growing as fast as the cloud providers, which means we are threatened by them,” said Andy Power, president and chief financial officer at Digital Realty. He added that “co-location” groups such as Digital Realty — where one party provides the real estate and customers provide the tech — “enable” the transition to the cloud and have seen an increase in leasing from many hyperscalers in recent years, rather than a dip.

Tech groups have made a noticeable shift towards greater leasing over the past six months driven by a handful of key companies, including Meta, Microsoft, ByteDance and Twitter. This uptick has reversed a previous trend towards greater in-house construction.

“I don’t think [hyperscalers] can keep up with the pace of their business on their own,” said Charles Meyers, chief executive officer of Equinix.

Power added: “These cloud service providers are blessed with lots of capital, yes, but they have better uses for it, honestly.”

Brendan Lynch, an analyst at Barclays, pointed out that in many metropolitan areas of the US, Equinix is the first- or second-largest data centre provider, giving the company a higher degree of pricing power. “That’s why we still like Equinix even though we realise there are some risks to our thesis,” he said.

One key risk is that should the land, labour and energy supply crunches ease, Big Tech groups may shift to constructing more of their own data centres.

For independent operators to maintain their appeal, differentiation is key, argue analysts. Most big businesses use a suite of different services, from Gmail to Workday, all hosted on different clouds. For all of these software applications to run smoothly together there need to be physical locations where data can pass quickly and seamlessly from one to the other.

Equinix’s “secret sauce” is this networking capability, according to Meyers, given it is nearly impossible for hyperscalers to replicate.

“Cloud service providers have spent billions building their own data centres,” said Nick Del Deo, an analyst at MoffettNathanson. “They have not spent a single dollar trying to replicate what Equinix has built.”

So-called “interconnection” constitutes around 35 per cent of Equinix’s earnings, as compared to 14 per cent of Digital Realty’s, according to MoffettNathanson calculations — though the latter has sought to expand in this market.

By contrast, Digital Realty, along with private groups CyrusOne and CloudHQ, have focused heavily on the bricks-and-mortar business. This segment is more vulnerable to increased competition from the big cloud service providers as well as smaller data centre groups that are being pumped with billions of capital from private equity firms and infrastructure investment funds.

“I do think there may be a glut at some point because everyone and their uncle is building data centres at the moment,” said David Friend, chief executive of Wasabi, a cloud storage company that leases from several data centre groups. “Right now there is an undersupply, but it’s going to be like oil prices: everyone is going to drill, drill, drill — and then it will force prices down until there’s greater consolidation in the market.”

Additional reporting by Harriet Agnew

Comments