Spread of western lifestyle hampers battle against cancer

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The good news is that about 40 per cent of cancer cases are preventable and that smoking, the biggest single cause, is in decline across much of the world. The bad news is that overall rates are shooting up as more countries adopt western lifestyles.

By 2035, the number of new cases is set to rise by 58 per cent to 24m, according to a report from the World Cancer Research Fund.

“Over the next 20 or 30 years, unless anything is done to stop it, [obesity or being overweight] is going to overtake smoking as the number one risk factor for cancer,” says Dr Kate Allen, executive director of science and public affairs at the WCRF.

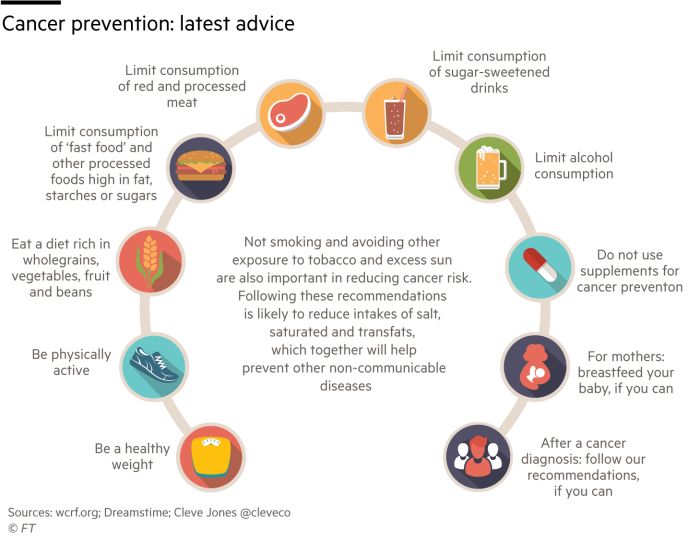

The report is a synthesis of a decade of research on cancer risks with a new set of recommendations (see graphic) to minimise a person’s chances of developing the disease. It says 12 cancers are now linked to being overweight or obese.

“It has taken 40 or 50 years to make a big dent in tobacco consumption,” Dr Allen says. In dealing with the problems of obesity, “it’s going to take at least that to get some traction,” she adds.

Linda Bauld, professor of health policy at the University of Stirling in Scotland, says: “We still don’t fully understand all the biological mechanisms for why excess fat causes cancer.”

This should not stop obesity prevention programmes, however, receiving the same priority as anti-smoking measures, Prof Bauld adds. “We have very poor provision of weight management services. The NHS and others really need to step up.”

Scotland is taking a lead on prevention. Around four in 10 cancer cases among its population could be prevented by changes in lifestyle, according to a paper in the British Journal of Cancer.

Scotland’s devolved government is planning to restrict the sale of crisps and biscuits, force calorie counts to be printed on food packaging and to clamp down on television advertising of junk food as part of proposals to halve child obesity by 2030.

It has introduced the world’s first minimum unit price for alcohol — a class-one carcinogen — and has been at the forefront of banning smoking in public places.

Cancer prevention strategies are especially important in poorer countries where cases are often diagnosed too late and options for treatment are limited.

Tobacco provides a sobering example. Prof Bauld, who is also deputy director at the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies, says the number of adult males smoking in the UK has dropped from 80 per cent in the 1950s to less than 16 per cent.

By contrast in low-income regions such as Africa, the rate is increasing. “Those markets are newer,” she says. “And a lot of the policies we’ve put in place through the [World Health Organisation’s] Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in high-income countries are not in place in low-income countries.”

Prof Bauld adds: “One of the successes in tobacco control is that there’s been a very clear enemy, but it has become much more complicated. The advent of vaping and alternatives to traditional cigarettes have enabled some tobacco companies to recast themselves as part of the solution.”

Ecigarettes are generally viewed more favourably by regulators in the UK as a way of weaning people off smoking, but in the US they are seen as a gateway to traditional cigarettes.

“Globally the tobacco industry is very powerful, often in bed with governments, and has managed to push back on high taxes, visible health warnings and smoke-free laws,” Prof Bauld says.

Adhering to the WCRF’s cancer prevention recommendations will have a “double or triple whammy”, says Dr Allen, namely in reducing the risk not just of cancer but of other chronic diseases.

Public authorities, however, have been called upon to play their part. Dr Allen says: “We need governments to enact policy so that the environment works with people and not against them, so they can make healthier choices more easily.”

Awareness campaigns are another crucial policy component. A study funded by Cancer Research UK shows a poor public understanding of the causes of cancer and a growing number of speculative assertions or misconceptions — often spread online — that conditions such as stress are a cause of the disease.

Some dangers, such as air pollution, are beyond the control of the individual. “Non-smoking lung cancer is a very under-appreciated condition,” says Jonathan Grigg, one of the authors of a 2016 report for the Royal College of Physicians on the long-term impact of air pollution.

Its carcinogenic effects have only really come to public attention in the past 10 years or so. Prof Grigg, who is also a founder of the Doctors Against Diesel campaign launched in 2016, says mitigation efforts by cities such as London are laudable but far too unambitious.

Policies in the Nordic countries and the Netherlands are much bolder, he suggests. Their combination of anti-pollution measures and the encouragement of “active travel”, such as walking and cycling, “could really make a big difference to people’s lives and also reduce things like cancer and cardiovascular risk”.

The WHO has sought to shift the international perception of air pollution as an environmental problem to being viewed as a public health priority. It has expanded its BreatheLife campaign to monitor air quality in 4,000 cities, highlighting the fact that nine out of 10 people worldwide do not breathe safe air.

Vaccination also has a role to play in preventing certain cancers such as those caused by the human papillomavirus, which is sexually transmitted and responsible for 5 per cent of cases worldwide.

Most countries inoculate only girls against HPV but there is pressure from campaign groups such as HPV Action in the UK for “gender-neutral vaccination”. English health authorities have extended immunisation to men who have sex with men.

As with other chronic diseases, cancer prevention makes economic sense. Faced with huge increases in cases and rocketing medical costs, “no country can afford to treat its way out of the problem,” says the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer.

“There must be an integrated approach, balancing prevention and treatment: embracing each, neglecting neither,” the agency adds. “Unfortunately, current investment in cancer prevention research and the implementation of preventive interventions is too low.”

Comments