Return to the office: FT readers discuss camaraderie, collaboration — and presenteeism

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Divisions, commutes, workloads — and bras — were some of the issues raised by worldwide respondents to an FT reader survey on the return to the office.

More than 1,000 readers, from London to Qatar, shared their concerns and hopes. There was optimism about hybrid working, as people across the workforce from sectors including travel, technology and financial services seized on it as an opportunity for both men and women to enjoy the companionship of the office as well as attend to personal lives. One observed a reduction in the so-called “Sunday Scaries”, as working from home on Mondays enables a smooth transition back to work from the weekend.

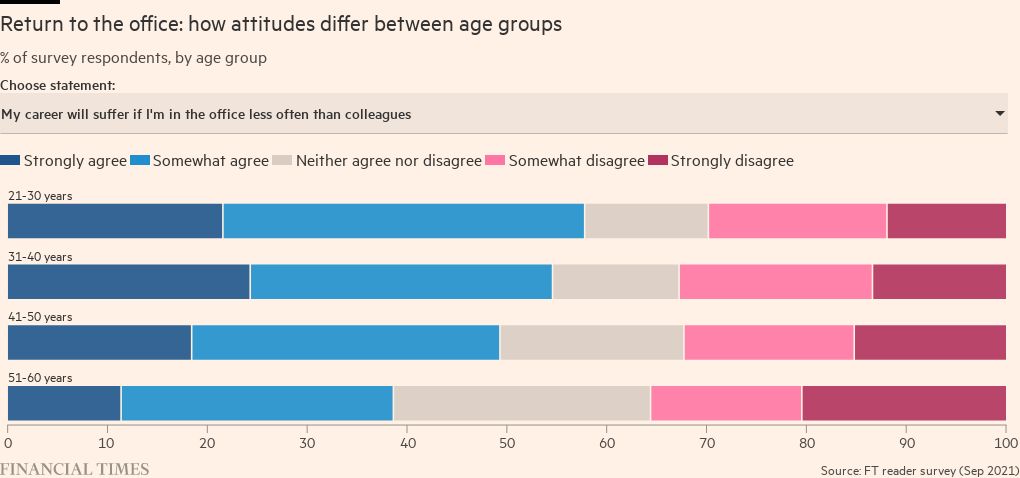

But there was also concern that flexible arrangements could falter because of poor management, and as face-time re-emerges as a feature of working life. One particular worry was that hybrid work patterns might intensify gender inequality. A manager in an international non-profit based in London likened presence in the office to working overtime: “Employers may not request it, but those who do it may well prosper in their careers.”

Gender: divisions or harmony?

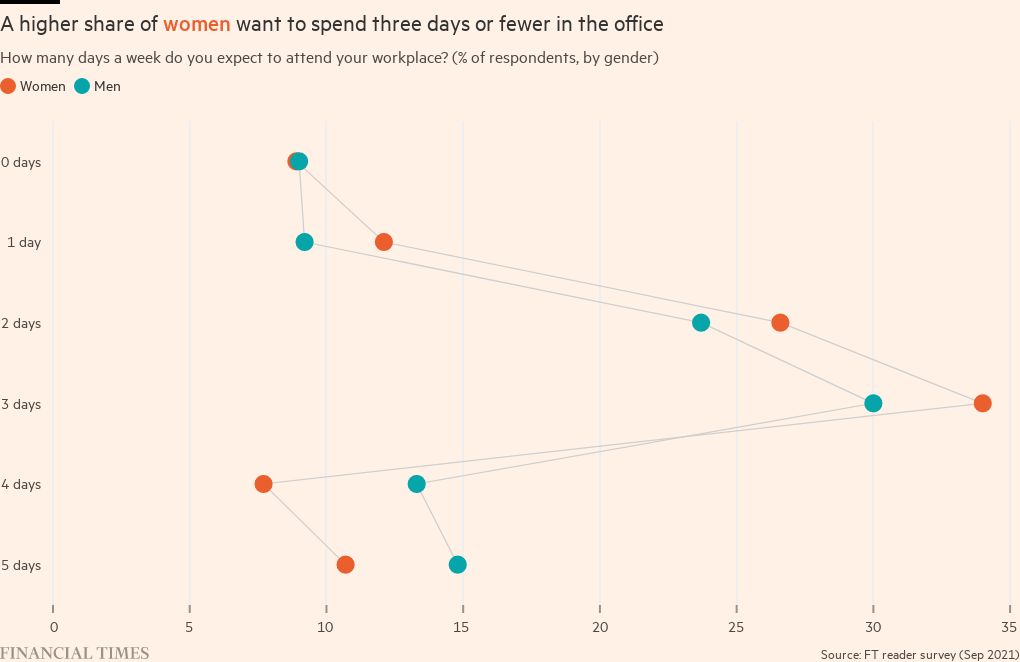

Men and women differ on their expectations about time spent at home and at the office. Almost three-quarters (73 per cent) of female respondents predict spending between one and three days in the office once all Covid-related restrictions lifted, with only 18 per cent opting for four or five days. Among male respondents, however, 63 per cent planned to come to the office for one to three days, with 28 per cent expecting to attend on four or five days.

Some respondents have already observed this trend in their workplace. “I was in the office today and there was one woman out of about 30 people,” said Michael, a London-based consultant. Meanwhile, David, a manager in Denmark, said that his “Covid semi-open office” had been “predominantly male”.

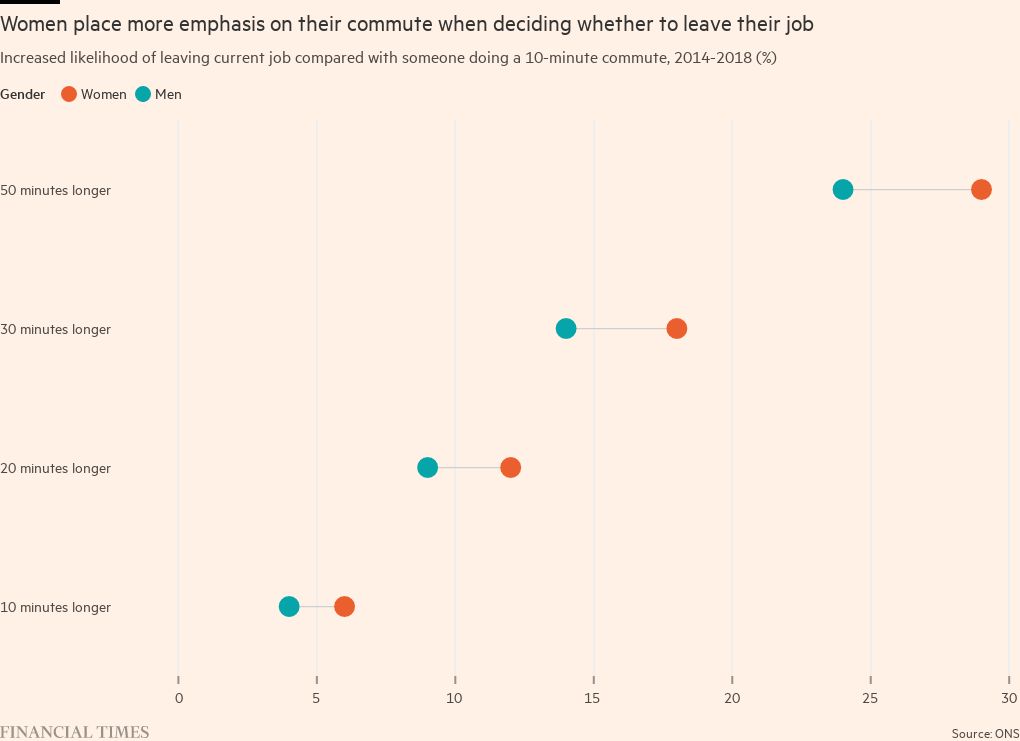

The fear is that this could reinforce existing inequalities in the labour market. Data from the UK shows that even before the pandemic, women were more likely than men to accept lower pay in favour of a shorter commute.

There was also a concern that women who chose remote work would pay a career penalty as old habits of presenteeism reassert themselves. Several mothers identified bias among male bosses who assumed they would work flexibly to manage childcare and domestic tasks, characterised as “less available”.

Some men acknowledged the risk. “I do worry that this will lead to systemic advantages for men in the workplace,” observed one male working in the non-profit sector in San Francisco.

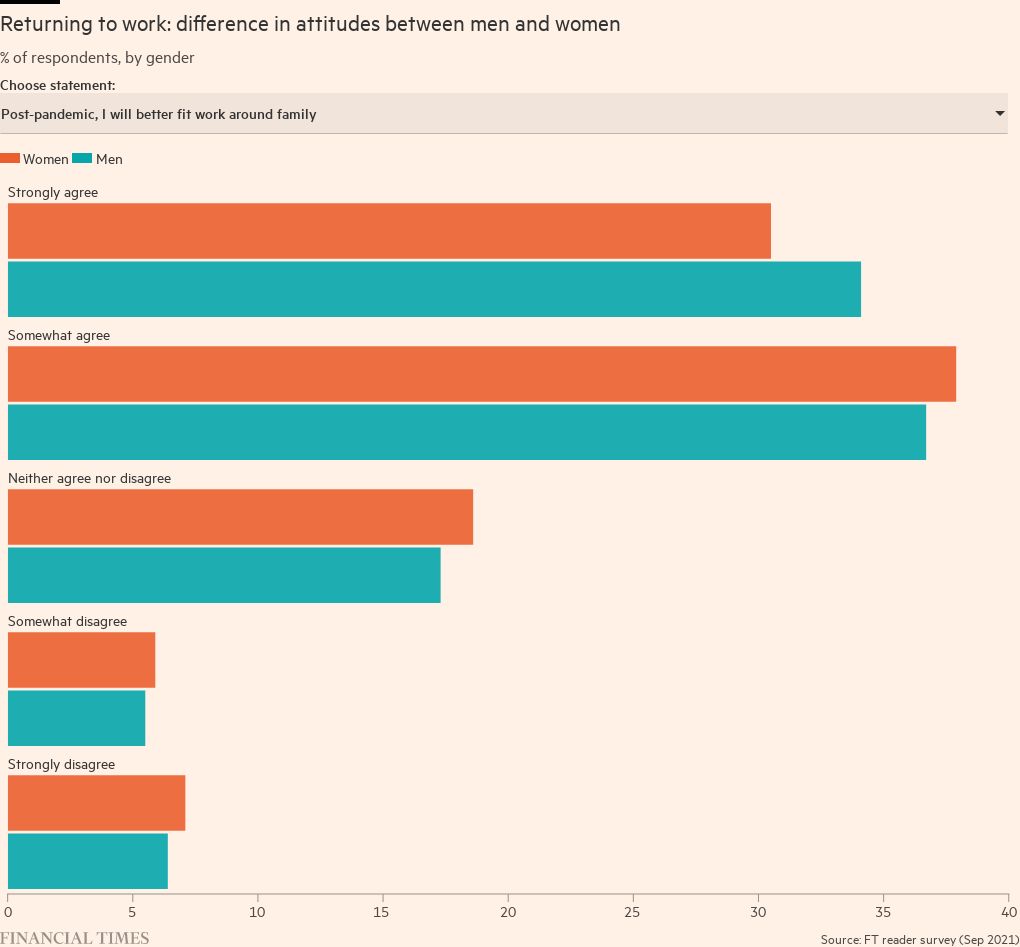

Others, however, were positive, noting that the experience of the pandemic had removed the stigma of homeworking, so that women would no longer be penalised for working flexibly and men could take on a bigger share of domestic duties.

There was also optimism that the future of hybrid working could support men who want to spend more time at home. One respondent hoped “men go in all guns blazing for their flex. Time to shake it up”. Indeed, evidence emerging through the pandemic indicated that fathers want to play a greater role in caregiving but find that their job hinders this, according to a recent report by charity Working Families, King’s College London and the University of East Anglia.

The pandemic demonstrated that people can be productive while working remotely. “Nobody will really know how much/little someone is in the office on a day-to-day basis. Performance will be more bluntly judged according to results,” said one investment banker.

The commute

Both men and women dread the drudgery of a daily commute. Readers complained of “pointless” daily journeys, travelling cheek-by-jowl with “reckless” people, of whom an “alarming number” did not wear masks. Others discussed “trekking into the office on designated ‘team days’ to do performative sitting at a desk when I could be doing the same thing at home minus the commute, [and] the risk of picking up a lurgy on the Tube [London Underground].” Roberto, a director in a Californian tech company, referred to a lengthy commute as a “severe time tax”.

In fact, research on the effect of the commute on innovation showed that “for inventors with long commutes, any distance you can reduce the commute, you can gain in innovative productivity”, according to assistant professor Andy Wu at Harvard Business School. The findings can be applied to a wide variety of skilled and creative workers, not just innovative high-tech types, he added.

It made readers question the function of the office. One 45-year-old woman working in biotech in Switzerland said her two-hour commute made her think that “it is cruel to force people back on the hamster wheel to help some employers relieve their fears of losing control”.

One recurring concern was that the pandemic had allowed the working day to expand. “Excessive hours worked from home are now expected in the office,” said one respondent, while others questioned how they would be able to manage their increased workload. “I currently work from 6am to 7pm from home. When I go to the office my working hours will revert to my pre-pandemic hours of 7am to 4.30/5pm. When I am in the office, I will step away from the keyboard more often and for a longer period of time . . . How will my lost productivity be recovered?”

Yet there was also hope the commute might help to contain the working day. Yasir Malik, a middle manager working in ecommerce in Toronto, Canada, said he planned to start shutting down his computer when he left for home — “something I did not do in this year and a half”. Another said: “The workday will finish as soon as I leave the office.”

Generational difference

Younger workers who responded to the FT survey were worried that senior staff will be reluctant to return, leaving them without guidance and unable to build contacts and social capital. “There are times when I’ll be sitting behind my screen not sure who to reach out to as I haven’t properly met everyone,” said one recent graduate. “My main worry is that my company being so flexible will mean people won’t come in which is a big disadvantage to new starters.”

Another young man, working in Zurich in asset management, said his main fear was “the risk of reduced chances of networking and a performance assessment entirely skewed towards a numerical and emotionless evaluation of analytical results”.

Respondents with disabilities or from minority backgrounds also noted that the remote work experience has been a boon to their working lives. One employee, who identifies as non binary, said “not having to face casual misgendering and being able to express my gender through clothing every day . . . is a huge boost to my comfort and quality of life”. A person with ADHD expressed relief at the ability to use a “fidget toy” at home without anyone staring.

Other research supports minorities’ preference for homeworking. Monthly surveys by a team of economists to track sentiment about the shifts in working arrangements because of the pandemic in America, found that people of colour want more time working from home compared with white people.

Inflexible managers

A clear majority of employees believe they will be able to choose how to split their time. This matters, as respondents who felt compelled to go into the office were far less happy. As one management consultant put it: “For me, it’s not about going to work on a particular day, it’s about flexibility to commute at different times. I might come into the office at 11am or leave at 3pm. Allowing that approach is real trust from an employer.”

Other respondents also felt empowered by a favourable jobs market to demand change. One wrote of winning remote working concessions after staff resisted their boss’s attempts to get them back to their corporate desks.

Some FT readers complained of managers’ refusal to adapt, due to conservatism or an inability to manage a hybrid future. “Personally,” said a male lawyer from Jersey, “I would like to see a formal policy adopted to give all employees the right to take some time — a day a week perhaps — as a work-from-home day.”

There was also a worry that without commitment there could be a slide back to pre-pandemic working patterns. “We are at the point now where it is a bit of a hindrance for someone to still be working from home,” said one respondent, “ . . . we will soon need to request approval to stay at home.”

The minutiae of office life filled some with dread. Despite admitting pleasure in seeing workmates, one person noted: “Bras, make-up, professional uncomfortable outfits, having to buy said outfits that I don’t really even like, 7am wake-ups to get ready for and commute to work, soulless fluorescent air-conditioned office with no windows and constant whispered bitchy conversations between senior management that are always still audible, having to buy extortionate yet repetitive and boring lunches again.”

Many feared losing the habits formed by remote working such as exercise and errands. “I’d rather do laundry on my breaks than chat,” said Rachel, a healthcare worker in Los Angeles. Some are resolved to try to stick to good habits developed during lockdown — from lunchtime walks and workouts to shedding uncomfortable high heels and taking a packed lunch to the office.

Between these two extremes, there was broad contentment with new freedoms to split their time between the office and home — with one reader calling it “the best of both worlds where you can boost productivity when home and boost collaboration when in office”.

Working It podcast

Whether you’re the boss, the deputy or on your way up, we’re shaking up the way the world works. This is the podcast about doing work differently.

Join host Isabel Berwick every Wednesday for expert analysis and water cooler chat about ahead-of-the-curve workplace trends, the big ideas shaping work today — and the old habits we need to leave behind.

Letter in response to this article:

Command and control is an outdated office mindset / From Heather Thomas, London EC2, UK

Comments