UK urban developers aim to lure ‘affluent achievers’ back to Derby

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

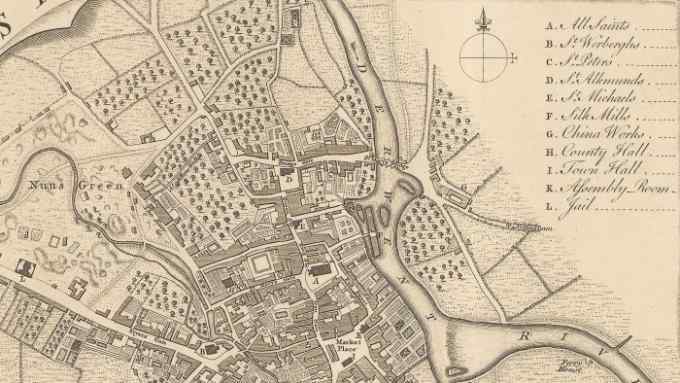

Derby is something of an unloved city in a much-loved county. Derbyshire, stretching from the English Midlands into the north of the country, is famous for its old mill and hill towns and Peak District walks. Derby sits to the south and is still casting off the grimier vestiges of its industrial past.

Given the chance, many Derby people have made off to such attractive towns to live in as Belper, Duffield and Ashbourne Green. In a relatively high tech, high paying local economy, they take their money with them, leaving Derby with the dilemma of how it can attract them back.

Inner-city development is one potential answer and, in this, history is playing its part. Florence Nightingale, the Crimean War nurse and “lady of the lamp”, is guiding the city forward. From the county, she helped design the former Derby Royal Infirmary, the expansive site of which is being recreated as the “Nightingale Quarter”.

“We spoke to Rolls-Royce people and some of their graduates said they wanted to live in the city rather than outside it,” says Donna Smith, sales director for Wavensmere Homes, which aims to sell 800 houses to be built on the site. Right by the railway station, it could not be more central.

Set amid “a lot of green”, cycle, running and walking tracks and an outside gym, Nightingale two-to-three bedroom houses are priced in the £185,000-£220,000 range. The first are due to be ready from October.

In February, the council approved the so-called Becket Well project in the city centre, which involves clearing the former Debenhams department store.

“It’s a major build-to-rent scheme,” notes Kathryn Allen, investment head of promotional body Marketing Derby. “As the housing market changes, so Derby’s affluent achievers will want to stay.”

“It’s easy to live your life here, visiting people, going to the doctors, putting your car into service,” says Adam Buss, chief executive of Derby QUAD arts and film centre. From Sussex on the south coast, he moved to Derby, one of the UK’s most landlocked cities, 14 years ago.

Mr Buss represents QUAD on the Renaissance Board, a consultation group brought together by the city council. It includes local private and public employers and other interested parties such as Derby County football club. “It means there is more attention to problems like rough sleeping,” he adds. “Not like in major cities, where it is can go unnoticed after a while.”

Locals are often quick to point out that if you are from Derby “you care about your place”. As one feature, the city has flourishing book, photography and other arts festivals.

Connectivity is an advantage. East Midlands airport, important for business as a freight and passenger hub, is nearby. Derby’s train links to leading UK cities are usually good. The journey to London takes about 90 minutes, though complaints can be heard about the Sunday service. The M1 motorway cuts between Derby and neighbouring Nottingham.

Derby people have little good to say about Nottingham. The feeling is usually mutual. However, one outsider who travels to work in Derby comments: “It pains me as a Nottinghamian to say that Derby is a safer city.” For people exercising a normal degree of urban common sense, Derby’s streets feel safe to be on.

The city has a lengthy history of immigration from Ireland and the Commonwealth, because of its long established rail industry and manufacturing tradition. Its vote in the 2016 referendum to leave the European Union — 57 per cent for Brexit and 43 per cent “Remain” — was higher than the national figure. Even so, EU funds are presently being used to shore up defences against flooding from the river Derwent.

“At its best, Derby is a welcoming place,” says one native, who works, with some regret, in London.

A point often noticed by people from southern England is how easy it is to engage local citizens in conversation. “People say hello,” comments one Derby dweller, rather surprised by this openness despite having moved in from the south years ago.

Comments