‘Our future is in Beirut’ – the designers helping to rebuild Lebanon

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

“I will start healing the day my city starts healing,” says Rabih Kayrouz, his eyes wandering over the iridescent Mediterranean. The Lebanese fashion designer was in his atelier in the neighbourhood of Gemmayze, a mile away from the Port of Beirut, when an explosion tore through the city on 4 August last year. Caused by the ignition of 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate, which had been improperly stored there since 2013, the blast destroyed much in its path. Within a split second, the business that Kayrouz had been growing over the past 20 years was devastated; he was also severely wounded. For someone like Kayrouz, who is so entrenched in this city, it’s clear that it will take much longer to start recovering from the trauma. But despite everything, the designer’s atelier – where he now stands – has been rebuilt, and he has created temporary solutions for the Lebanese arm of his business.

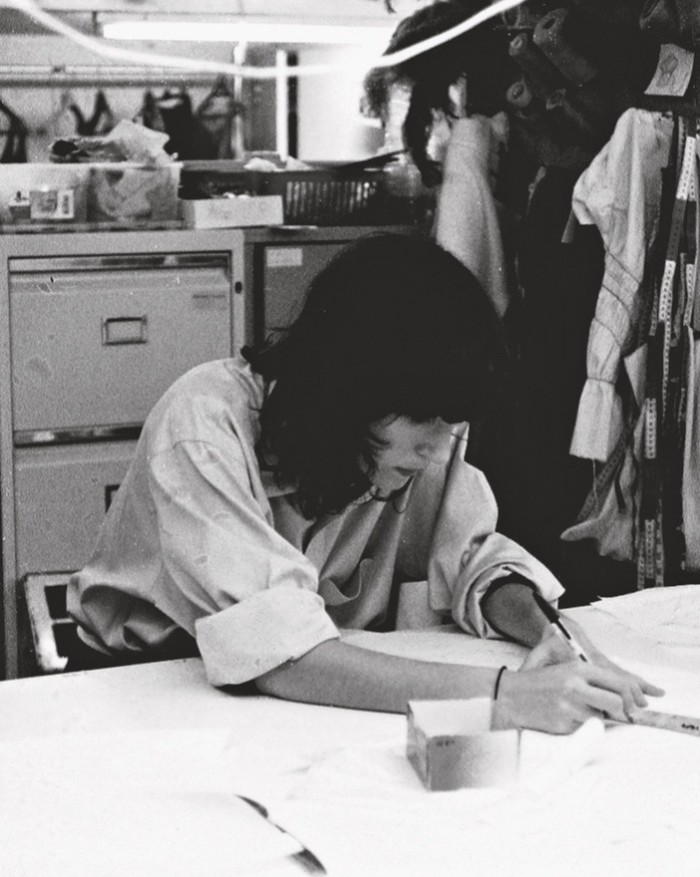

To continue functioning in a country where nothing functions is in itself a miracle. However, such resilience should come as no surprise. Kayrouz was always a pioneer in his field. In 1995, after pursuing his studies in Paris, he came back to Beirut, then considered “the city of possibilities”, he says. “The war had ended a few years before, and a creative scene was being fuelled by the desire to simply do things.” Since 2009, the designer has had one foot in Paris, home to his prêt-à-porter business, and one foot in Beirut, where 12 employees focus on custom-made orders. Even in October 2019, when Lebanon’s latest economic crisis hit, instead of investing his efforts solely in Paris, Kayrouz rolled up his sleeves and explored ways to make his business viable. “It’s something that I find hard to explain, but no matter what happens in Lebanon, the minute I land here, I just feel like giving.”

Following the blast, he participated in raising almost $400,000 via the United for Lebanese Creatives fund. The organisation helped rebuild spaces for some of the young designers of Starch foundation, an NGO he co-founded in 2008 with designer Tala Hajjar to launch emerging Lebanese designers. On a professional level, Kayrouz revisited his business model from scratch: “What matters the most to me today is to adapt to the economic crisis Lebanon is going through. One could think that fashion doesn’t make sense any more, but I’d rather look at it differently. Why couldn’t we keep on creating clothes, while integrating a new system of execution that would fit those hard times and be respectful towards our clients?”

The designer conceived special collections sourced from deadstock fabric, fully produced in Lebanon and sold in “lollars” (US dollars within Lebanon’s collapsed banking system, which depositors have been blocked from accessing or transferring abroad, or can withdraw only in local currency at a low rate). Those items “take into account the financial difficulties of our clientele, allow them access to some beauty, and also support the families of the employees at Maison Rabih Kayrouz.” He continues: “But all of this is more crisis management than a long-term roadmap. It’s just a solution to stay in Beirut, and help it as much as we can.”

Kayrouz is one of many creatives determined to help the city thrive again. Fashion designer Elie Saab, who is also based between Paris and Beirut, is donating a contribution from the sales of his fragrance Le Parfum throughout 2021 to Unicef’s programme to help vulnerable girls in Lebanon. A group of jewellers, including Gaelle Khouri and Noor Fares, donated designs to a fundraiser hosted by retailer Auverture, which raised more than €51,000 for the Lebanese Red Cross and Lebanese Food Bank.

But more striking are the efforts being deployed by creatives to keep businesses alive and stay inspired in an environment where beauty is not considered a priority. “In these difficult moments, luxury is not a first necessity, but it is part of the vital economical wheel of any society,” says jeweller Selim Mouzannar. His business is based in Tabaris, among the worst-hit neighbourhoods; his shop and atelier were badly damaged in the blast. “You can destroy the walls, but you cannot change the spirits,” he says. The Kant quote “Optimism is a moral duty” is plastered on the windows of his new workshop, which has since been rebuilt. His decision to stay is not solely because relocating seems logistically and financially impossible, but because the city provides him with creative stimuli. “Beirut will remain a source of wisdom and culture and freedom; justice and peace will prevail. Beirut is my city and we are the real peaceful resistance. I am here to stay.”

That’s also the case for furniture and homeware label Bokja, which recently extended its distinct, patchworked aesthetic into ready-to-wear, which is all locally produced. “Our future is in Beirut,” say co-founders Huda Baroudi and Maria Hibri. “We owe it to our team of artisans to continue our growing legacy in craft, preserving an age-old tradition, a language that would otherwise begin to dwindle. A strong local presence is paramount. It is during these fragile times in the country that our roots sink deeper; we don’t plan to jump ship anytime soon.”

Both Baroudi and Hibri were quick to place their skills at the service of the people following the blast. “We immediately transformed the showroom into a community centre, offering it to local organisations on the ground which can dispense aid. As dedicated menders and fixers, we offered to repair and re-upholster damaged home goods from the most affected areas. A signature suture was used to stitch the pieces back together by our team of specialised artisans. Our aim was to offer a message of hope through preserving snippets of people’s homes.”

Even younger creatives, who were already struggling to sustain their businesses amid the successive crises, took part in rebuilding. Tatiana Fayad and Joanne Hayek, the co‑founders of accessories and clothing brand Vanina, found their ateliers and store in Gemmayze completely in ruins, but started reconstructing the spaces the very next day. “We cannot fall” was their motto. The two women, both in their 30s, hold the reins of a social enterprise that encompasses a network of 70 women artisans. “Today, more than ever, we are determined to continue expanding our brand internationally, grow our local network of creation, and support our family of artisans.”

This is indicative of a broader issue that Cynthia Merhej, creative director and founder of fashion brand Renaissance Renaissance, explains: “As soon as the blast happened, I had to relocate to Paris, as it was impossible to have my business in Beirut, with the destruction of the banking system and the country’s infrastructure.” From there, Merhej started a GoFundMe for three Beirut creative businesses she knew would be left out of the recovery effort. “For me it was extremely important to help these creatives and business owners, because I could not see any future for our country if we did not have creative people in it and driving it. We successfully raised €50,000 and distributed the funds equally amongst the three recipients. It was the fastest way to raise money and get it to them, even though it was extremely difficult to do that with all the issues with the banks.”

That said, Merhej is as committed as her elders to stay rooted, at all costs, in Lebanon. “I am keeping my atelier in Beirut and I will finally be able to travel there this summer, to work on creative development,” she continues. “It’s important for me to still find ways to support our local fashion economy there. I hope once the pandemic is over, I will be able to go back and forth much more.”

This year, Merhej’s brand Renaissance Renaissance reached the semi-finals of the LVMH Prize. Proof, if needed, that even from afar, and against all the odds, this intrepid “young guard” of fashion will always manage to keep their country on the map. And give hope to a possible, and much brighter, future for Lebanon.

Comments