Lucy Kellaway interviews Everyday Sexism Project founder Laura Bates

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Laura Bates sits on the sofa in her garden flat in north London with her legs tucked under her. She is wearing a flowery dress and a cardy and is playing with her hair, which is long and blonde. Her 27-year-old skin has not a single line on it. She is very pretty indeed.

Ought I to have told you any of that?

In her manifesto, Everyday Sexism, Bates argues the way journalists describe political women is all wrong. It is not OK to go on about Theresa May’s shoes or Hillary Clinton’s cleavage. So is it all right, I ask this fourth-generation feminist, if I let FT readers know that she is blonde and pretty in a flowery dress?

Only if it is relevant to the article, she says. I tell her it is – an interview should say what someone looks like as it gives an idea of them.

“But would you write that a man was good looking?” she asks, enunciating every word and delivering them with a righteous certainty that could be alienating but is instead making me feel shifty and somewhat in the wrong.

I protest that I would. Bates looks doubtful and later sends me some stats to prove her point. Average number of words I have used in recent interviews to describe a woman’s appearance: 150. For a man it’s only 41.

“We live in a society where if we hear that a woman is pretty or wearing a flowery dress, we’ve been pre-primed to slightly lessen our idea about her intellect and to slightly think that she’s not a political person,” she says.

Just in case any readers are subliminally knocking a few points off Bates’s IQ on the strength of the blonde hair and the dress, they are making a big mistake. They are making an even bigger one if they think she is not a political person. Even before meeting her, I have undergone an unsettling change of heart, and dumped almost all my beliefs on what it is to be a woman in Britain. The Everyday Sexism Project, which she founded two years ago, has got through to me in a way that the writings of Camille Paglia, Natasha Walter or Naomi Wolf never have. For the first time since the 1970s, I find myself cross on behalf of women, and rather inclined to take up cudgels. What has swayed me are not statistics or arguments but real stories of sexism. So far she has collected more than 60,000 of them, which sit there online, hard to ignore or dismiss.

It happened almost by accident. Until a couple of years ago Bates, an English graduate from Cambridge, was trying to make a living as an actress in London. She was getting fed up with acting in wardrobe commercials and being told to vamp it up, and tiring of reading casting notes that said: “She’s virginal but she’s also a vixen” or “She’s f***able yet naive”.

She’d also had enough of being hassled by men. “I had all these experiences of being groped on the bus, having a man follow me home, having a guy in a car slow down and say, ‘You walk down here every Wednesday and Thursday at about 12, don’t you?’” So she started to wonder: “Is it my fault? Is it something I’m wearing?”

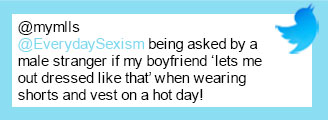

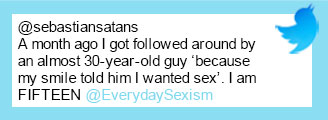

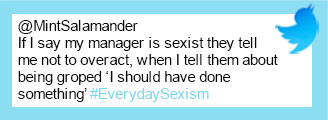

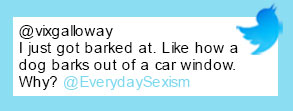

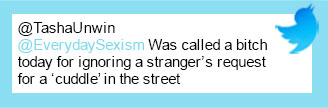

To find out, she started a website to see if other women felt the same. She expected to get about 50 stories but, after two months, had more than a thousand. Now Everyday Sexism has 159,000 followers on Twitter, and there have been hundreds of thousands of tweets reporting sexist incidents. Some are minor; others are not minor at all.

…

I became vaguely aware of the movement about a year ago when I saw tweets from women ending #EverydaySexism, or #shoutingback. At first I took no notice. Hashtags are annoying and, in any case, these didn’t fit with my view on feminism, which went roughly like this. Things have got immeasurably better for women, especially white, middle-class ones. The big battles have been won. When women are discriminated against they have the law on their side. When they come up against more trivial sexism, they should reply with a brisk “Sod off” (or ruder), and save their rage for the women in India or Saudi Arabia, who have worse problems than occasionally being whistled at.

My own life has provided me with no cause for anger, and much reason for gratitude. At work, I’ve been promoted, pushed forward and invited to things, because everyone is so desperate to show they have a few prominent women around. As for sexist attacks, apart from once on a metro platform in Paris when I was 17 and a few remarks from traders when I worked in the City in my early twenties, I really don’t think I have come across any.

Yet what is unfolding on Twitter describes a different world. On the day of the interview, most of the stories are from women who have been masturbated at in public. “I was on the Tube sitting, he was standing in front of me, hand down his pants,” reads one. Another goes: “Broad daylight. Heard someone walking right behind me, was guy masturbating. The angrier I got, the more he was getting off.”

The really bad bit, says Bates, is not just that this goes on all the time but that no one takes any notice. “When it happens on a bus or a Tube and every other passenger looks out the window, it sends such a strong message, both to the victim and the perpetrator, this is normal, this is OK.”

As she talks I am wondering about the parallel universe in which I live. How come I’ve never witnessed anything remotely like this? Maybe my appearance has had something to do with it – even when I was in my twenties I looked like a prepubescent boy. I remember once walking past a building site with a large-breasted friend and being horrified at the cacophony of catcalls she attracted.

Bates insists it is not all about looks. Women of all ages get shouted at in the street, and not just the obviously sexy ones. “We hear so many stories from women who are shouted at by men who call them fat bitch or ugly c***.”

The second possibility is that I have blinded myself to sexism because I don’t want to see it. Lots of people do this, she thinks. Yet there is a third, and much more troubling, explanation. And that is that since I was young, and since Bates left her sedate private school in Somerset, things have got much worse for girls and young women.

“I was in a school last week and I asked the girls if there are any situations where women are not treated with respect. There was an uproar, all of them shouting: ‘Yes, the boys in our year call us sluts and slags more than they use our real names. Yes, we’re told that we have to send them pictures of our breasts and if we don’t, then we’re uptight and we’re prudes.’ This stuff isn’t, like, isolated incidents. This is stuff that’s coming up again and again.”

Almost more troubling is that boys, Bates says, increasingly silence girls who raise their hands in class with the taunt “Get back in the kitchen”. It strikes me as extraordinary that these boys – whose mothers may have been feminists in the 1970s – would be using a phrase that was outdated 40 years ago. What is happening?

“I just don’t know,” she says. “I’m not qualified to say.”

If the strength of hashtag feminism is that it is free of theory and mumbo jumbo, its weakness is that it’s rotten at providing reasons. Bates keeps repeating over and over again: she doesn’t have the data. She is just collecting the stories. But when I persist, she says it is probably because of the internet.

In other words, the very thing that has created this new wave of feminism, in which it is easy for women to share outrage online, seems to have also created a great environment for misogyny.

“At university there are ‘spotted’ websites where a girl can be bending over to get a book in the library and by the time she gets back to her dorm she finds that a picture of her underwear coming up out of her jeans has been posted on a Facebook page dedicated to her university and everybody is commenting and making sexual remarks about her. That’s different. That’s new.”

More worryingly, young girls are finding out about sex from boys who have been watching internet porn in which women frequently get hurt – with the result that they end up thinking that sort of thing is normal.

Yet even nastier than that is the way the internet makes it so easy to launch vicious, anonymous attacks on virtually anyone. Bates knows this at great cost.

“I have had emails from people saying: ‘You should be very afraid, little girl, I will get you.’ People talk about specific serial killers they admire and who they would like to emulate . . . and about the different weapons that they fantasise about using on you and in what order. It is quite twisted stuff. When you’ve read somebody’s detailed account of how you’ll be raped and tortured, when you go to bed you think about that.”

It all makes me think that being this earnest, composed woman can’t be that much fun. Bates works for nothing, supporting herself mainly through journalism. And, as well as having to deal with internet psychos, every day her job is to be up to her neck in the horrible things that have happened to other women.

The only light relief is that she is soon getting married. But even that isn’t as light as all that. The Saturday before we meet she wrote a magazine story for The Guardian in which she pondered such questions as whether it is acceptable to get married in white or to keep one’s own name, and whether women as well as men should make speeches.

I was baffled by these dilemmas – surely the question of the white dress was solved a long time ago: wear one if you want to; not if you don’t? Since the 1970s women have been keeping their own names and giving speeches. I did so at mine 25 years ago, not because, as she suggested, I was infiltrating a patriarchal institution but because I felt like it.

Yet every time I refer to what we did in the 1970s a slightly glazed look crosses Bates’s face. Politely, she points out that she can’t comment as she wasn’t around then. When I say that previous generations of feminists have failed pretty drastically if men are behaving in even nastier ways than before, she shakes her head. She is not interested in blaming, only in raising awareness now.

Yet some of the old guard don’t return the compliment. Germaine Greer has been very sniffy about Everyday Sexism and in a review of Bates’s book complained: “Simply coughing up outrage into a blog will get us nowhere.”

Bates agrees that coughing up outrage is not an end in itself but says that it changes things by making people more likely to act. “We hear again and again and again from people who have reported things to the police as a direct result of reading those things and realising that it would be taken seriously.”

In any case, the blog is becoming an increasingly tiny part of what she does. As a result of her work, 2,000 transport officers have been trained to spot sexual abuse on buses and trains. She is pushing for education in classrooms to teach children about relationships and is also talking to large companies about how to reduce sexism at work. And the fight is spreading beyond the UK: the website has launched in 20 countries with another 15 on the way.

…

Two years in, there is no question of giving up and going back to acting. Neither does Bates have any ambition to go into politics – she won’t even say which party she supports. “It’s so much bigger than that. It affects everybody regardless of what party they vote for.”

Instead she has landed a role that suits her perfectly. Articulate and persuasive, she is the ideal campaigner. And though she will hate the thought, her looks help. The media love a pretty face.

But the media also have a very short attention span. Does she worry that the world will soon tire of her and #EverydaySexism?

“This is no longer anything to do with me at all. It’s about the 60,000 women’s voices and the strength of those stories. Regardless of whether someone wants to interview me next week, it doesn’t matter at all as long as people are still fighting.”

As I leave, I ask what her husband-to-be makes of it all. “He’s just as passionate about the whole thing as I am,” she says.

But then she tells me about a time when they were watching a DVD in which a woman gratuitously takes off her pyjamas. Bates protested, and on that one occasion only, her boyfriend demurred.

“He was, like, ‘I know. But can we just watch the movie?’”

——————————————-

lucy.kellaway@ft.com. ‘Everyday Sexism’, by Laura Bates, is published by Simon & Schuster (£14.99).

All tweets are taken from the @EverydaySexism account or #everydaySexism on twitter

Photographs: Kate Peters; Getty; Don Arnold

Comments