Invest now to repair ‘huge’ learning loss, educators urge

When Nigeria closed its classrooms last year as coronavirus spread across the country, Folawe Omikunle mobilised her fellow teachers to keep children learning. She hopes their innovations can be adapted and extended as pupils now return to school.

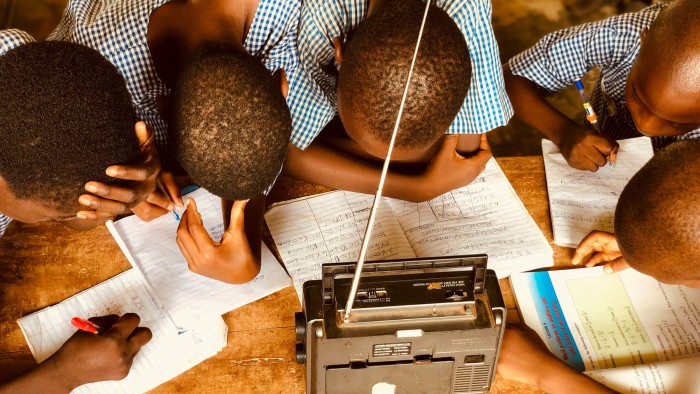

Staff made home visits to offer tuition, developed worksheets and online quizzes to make learning more fun and interactive, and broadcast their lessons on local radio stations to isolated communities that lacked digital connections.

“The pandemic created an opportunity to engage with a challenge that existed before Covid-19, in providing alternative ways for kids to learn — to close the gaps and reach as many as possible,” Omikunle says.

Like her counterparts around the world, she is turning her attention to assessing the emotional and learning setbacks caused by months out of school. They hope to help students catch up and to “build back better” or — in the latest mantra adopted by educationalists — to “build forward better” for the coming generations.

The task is significant. “There is a major crisis as we start to see the full impact of closures,” says Audrey Azoulay, director-general of Unesco, who gathered ministers from around the world at the end of March to take stock of the fallout from coronavirus. “It affects everyone.”

One concern is that so many children remain out of the education system. Unesco estimates that schools in just 107 countries have fully reopened, with those in a further 30 fully closed and those in another 70 only partially open. Almost 1bn learners are still studying remotely, with a “digital divide” further discriminating between richer and poorer students within and between nations.

Teachers are starting to take stock of the consequences for those who are returning to class. Many children have fallen substantially behind in their learning, and faced emotional and sometimes physical trauma while out of school.

The damage is greatest in lower and middle-income countries, where the pandemic has accentuated often poor quality underlying provision and children face higher economic and social barriers to achieving their potential.

“The learning loss has been huge,” says Kassaga Arinaitwe, head of Teach for Uganda, a non-governmental organisation, which has helped create “community learning pods”. These involve teachers travelling to villages to give open-air lessons to small groups of children. “Seventy to eighty per cent have not been able to learn online,” he explains. “Many are so behind, it will need an entire year to bring them back up to speed.”

Arinaitwe is also concerned that many students will never return to school at all, most notably a significant number of young adolescent girls who became pregnant or started working to support their struggling families.

Juliet Wajega, former deputy general secretary of Uganda’s National Teacher’s Union, warns that many staff who were left unpaid for months have also quit the profession. “Some are now earning more than when they were teaching and won’t be willing to go back unless the salaries are really good,” she says.

Many practitioners fear it will take months to measure the extent of the Covid-19 setbacks, and years to recover. Unesco estimates the number of children lacking basic literacy levels rose to 584m last year, setting back two decades of progress and — without substantial additional measures — requiring 10 years to get back on track.

The World Bank calculates the lifetime costs of children dropping out, falling behind and earning less could be $10tn.

A first priority is fresh funding, which will not be easy against a backdrop of the global economic slowdown. That has squeezed domestic resources and undermined the capacity and political commitment of donors to help — not least the UK, which has slashed its aid budget from 0.7 per cent to 0.5 per cent of Gross National Income.

One yardstick will be whether the UN-backed Global Partnership for Education achieves its five-year replenishment request from donors: of $5bn of fresh support by this July. But Sarah Brown, chair of Theirworld, an education charity, says that target is a fraction of the $75bn her organisation calculates is required to meet the goal of quality universal education by 2030.

Working with her husband Gordon Brown, the former British prime minister, she hopes by late this year to persuade governments, philanthropists and companies to back a proposed multibillion-dollar International Finance Facility for Education.

Their pledges would underwrite cheap borrowing by international development institutions, multiplying the sums that could top up education budgets in lower income nations.

“If countries are having to make less money go further, this is a way to generate funds to restore investment in young people and put an end to the crisis that is building,” Brown says.

How such money for education recovery is spent will be pivotal. Mubuso Zamchiya, managing director of the Luminos Fund, which runs programmes for marginalised children in Ethiopia and Liberia, cautions: “Just because schools reopen, it doesn’t mean the problem of learning loss is over.”

He stresses the importance of measures including feeding programmes for poorer children, and the value of innovative approaches such as those of his organisation, which uses play, dance and music, and places responsibility on children to “own their learning”.

“There isn’t one silver bullet,” cautions Maliha Khan, chief programmes officer at the Malala Fund, co-founded by Malala Yousafzai, the activist and Nobel laureate, which supports advocacy by local communities for greater investment in education, especially for girls. “A lot of governments are taking their foot off the accelerator just when they should be doubling down on that investment.”

Digital solutions will still be needed, according to Gaurav Singh, chief executive of the 321 Education Foundation in India. This charity has developed learning resources for students who have access to a phone for just a few minutes a day. “We’ve learnt that a lot can be done online,” Singh says. “Technology can never replace the teacher but it can stimulate learning and free up their time to help tailor instruction,” he says.

Wendy Kopp, chief executive of Teach for All, a global network, says coronavirus has helped unleash the powers of both technology and of people — notably by increasing engagement between teachers, parents and their communities, to support children.

She argues that investing in future educational leaders such as those in Uganda, Nigeria and Kenya is essential. “The question is: how we do not go back to the status quo, but really come together in communities and leverage the new possibilities we’ve seen to come back much better, post-Covid.”

Comments