‘I kind of gave up’: how academics in danger rebuild their lives in exile

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

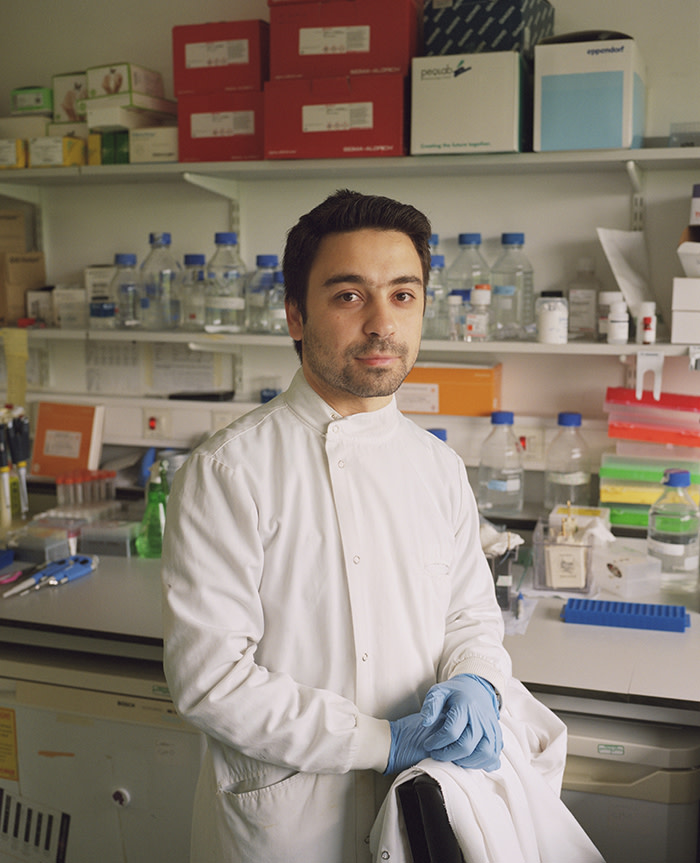

A few minutes after meeting Zaher al-Bakour in a Caffè Nero on Aberdeen’s Union Street, his phone rings and he swipes to decline the call. It is just his sister, he says. Mortified that he should do this to someone WhatsApp-calling him from rebel-held territory in Syria while we chat over croissants and cappuccinos, I suggest that he call her back. She thinks her nine-year-old daughter has typhoid and, since there are no doctors there, wants al-Bakour, an academic who specialises in pharmacology, to analyse the case. He can’t. Though he spends his days in a white lab coat tinkering with test tubes and microscopes, “I’m not a doctor,” he says.

It’s a cruel twist to a modern war. Imagine that, in 1943, you could have called Aberdeen from the Warsaw ghetto. Indeed, in a way al-Bakour, a 27-year-old from conflict-torn Aleppo, has ended up in the granite “grey city” because of the Nazis. He is an exiled academic who has been brought to Britain by the Council for At-Risk Academics (Cara), a British organisation founded in 1933 to help German-Jewish scholars who were fired when Hitler came to power.

That same year, Albert Einstein made a powerful speech in London’s Albert Hall to raise funds for the organisation. Of Einstein’s generation, 16 of those who were helped by Cara went on to win Nobel Prizes. Then, like geological layers of war and terror, came Hungarians in 1956, junta-fleeing South Americans, South Africans in flight from the apartheid regime and, now, those from the Middle East.

There are tens of millions of refugees in the world but al-Bakour is part of a tiny and exclusive group plucked to safety by fate and talent. There are currently just 280 Cara fellows. Its mission has remained strikingly simple over its 85-year existence. If you are an academic who has taught, and is in danger, you are eligible to apply for help. “It might be because they’re caught up in conflict, or maybe their university has physically been attacked, or maybe there were militias interfering with the work of universities,” says Stephen Wordsworth, Cara’s executive director. “Or it may be something they’ve written or said. Essentially, it’s still about helping people who need to get away.”

The fellowship gave al-Bakour the means to escape from Aleppo and, ultimately, to pursue a PhD at Aberdeen University. Up until then, his university experience had mostly been lived under siege. First, as war broke out in 2011, there were demonstrations at Aleppo University against President Bashar al-Assad. The security forces intervened and people disappeared. Did he know what had happened to them? No, he says, he was simply too terrified to ask. Then fighting began. Rebels seized his street and no one in the family dared go out for a month. When they were pushed back, he returned to the university, which was shelled three times. Once, when he and 125 others were taking an exam, shells hit nearby buildings. They ducked under their desks and came out again when they heard the ambulances arrive. Then they were granted 10 minutes’ extra time.

When he arrived in Scotland in late 2016, al-Bakour’s biggest shock was the weather. “It was cold. But even now, after one and a half years, if you ask me, ‘Do you believe you are in Aberdeen?’ I say, ‘No.’ I live with my memories from back home in Syria, and I always have that sustained pressure of thinking and praying and worrying about everyone in my family.”

Over the past couple of months, I have met a number of academics who have been offered similar routes out of their troubled homelands. Yet their stories are strikingly different. For Mohin Rahman (not his real name), death seemed imminent in Bangladesh. In August 2015, an Islamist group called on Rahman, an electronic and telecoms engineering teacher at a university in Dhaka, and 18 others “to prepare for being killed and to have repentance for what [they had] done against religion and their prophet”. Living under virtual house arrest, he slept with a knife under his pillow. “I knew that even if I was to be killed I could protect myself at least for a tiny bit,” he says.

Leila Alieva, 56, is a political scientist from Azerbaijan. She reminds me that she once briefed me on the situation there when I visited the country as a reporter. Today, she has finished her fellowship at St Antony’s College, Oxford. She now has a rare “exceptional talent” visa allowing her to stay in the UK but has yet to find work. “You don’t start looking for a job at my age,” she says.

It was never easy being an independent thinker in Azerbaijan, a notoriously authoritarian state with a history of human rights abuses. However, says Alieva, two things in particular made the government paranoid — the 2014 uprising in Ukraine and the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey. Activists and journalists began to be arrested, with some charged with espionage for Armenia, Azerbaijan’s old enemy. Alieva was accused of being a western “fifth columnist” and, more prosaically, of tax evasion. Her friends told her to flee but she did not want to, not least because her mother was ill and needed caring for. “You are making a big mistake,” they said. “They intend to arrest everyone.”

She began to study prison conditions and thought: “I might not survive.” Her sick mother was in bed. Alieva told her they were going to Georgia to see doctors, bundled her into the car and that is how her exile began. I don’t need to ask what the darkest moment was for her. It seems too cruel, but it is also obvious. Cara arranged the fellowship in Oxford but she had no money or visa for her mother, who went home to Azerbaijan. They skyped twice a day until one day her mother died of a heart attack as they chatted.

Naif Bezwan, 56, is the first of the academic exiles I meet. The Kurdish political scientist has been a fellow at University College London since June last year, following his expulsion from Turkey after the failed coup in 2016.

Exile has energised him, he says. He and colleagues are working to help other academics from Turkey who have been fired or are in prison. Bezwan is an old hand at this. As an undergraduate in Turkey in the 1980s, he was arrested twice for political activism. Deciding that as a young and ambitious Kurd he had no future in Turkey, he fled to Germany, where he eventually became an academic. “You had this sense of doing something new and inventing a new world,” he says.

By 2014, a peace process of sorts in Turkey had brought a halt to fighting with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and a relaxation of the draconian treatment of Turkey’s Kurds by the government. Bezwan was invited to go back to open a political science department at a university in Mardin in south-eastern Turkey. He recalls his joy at being part of this changed atmosphere. He opened his first lecture with the words “good morning”, not in Turkish (“Günaydın”), the language he was lecturing in, but with the Kurdish “Rojbas”. There were some 50 students in the lecture hall, he says, and for a moment there was utter silence. Then they chorused “Rojbas” back to him. “I explained why it was important, after years of not being in my native country, and being at a university speaking to Kurdish students, to say one word in Kurdish.”

He recalls how, during this brief period of Kurdish renaissance, he “did something meaningful for me and for wider society and for my students”. Then, in January 2016, when fighting had begun again, he signed a peace petition and was immediately suspended for “supporting a terrorist organisation”. The authorities employed a divide and rule strategy. Some faculty members were called upon to take part in investigations of others. The atmosphere turned poisonous. Then came the failed coup attempt in July and in August Turkish troops entered the Syrian fray. Bezwan gave a newspaper interview arguing that Kurds needed unity. He was instantly fired, but other academics were being arrested. Fearing he would be next, he gave a final defiant and unofficial lecture to his students and fled to London, where Cara organised his UCL fellowship.

Wordsworth says applications reached a peak in late 2016, due to a combination of events in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey after the coup. “At that time, we were getting 15-20 inquiries per week.”

He explains that Cara is able to carry out its work because it has support from more than 100 universities, who provide places and funding. Despite this generosity, he says, not all of the universities can afford to fund multiple postings, so the challenge is generating extra funds.

“There are more people needing help than we can process. With more people, we could do more things,” he says.

Ethel Maqeda, 46, was not involved in Zimbabwean politics. She taught literature and theatre at Harare University. But her husband was and, when he fled in 2005, she followed. She arrived as a refugee in Barnsley, Yorkshire, with two small children and says her confidence deserted her. “It was cold and dark and I could hardly understand any of the English.”

The couple were granted asylum within weeks, but once they got it there were no more benefits and they were utterly on their own. She found an agency that did catering and other jobs. For her, the darkest period was not when she feared arrest or worse but when she ended up in a uniform embroidered with the words “classic cooking”, ladling out lunch to students and then clearing up their mess. Very early on, she says, she understood that she just had to “do what needed to be done”. You can’t dwell on the fact that “you are not at home, the fact that you were this person with a house, life and bank account and with some standing in the community and here you are nothing and you are always broke with barely enough food”.

After a year Maqeda’s husband left for South Africa to continue the struggle. By 2010, her first asylum visa had expired; the agency mistakenly said that as her status was now unclear they would not give her any more shifts. She was in debt but enrolled and studying at Sheffield University. She sent her boys, then aged nine and 11, to live with their father. After she was granted a new visa, a fluke meeting changed the entire course of Maqeda’s life. In the street she bumped into another Zimbabwean who told her he was finishing his PhD and mentioned an organisation he had heard of called Cara. She applied and in 2012 began her own PhD on violence in Zimbabwean fiction. Recently, she became an associate lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University.

The fall of Mugabe last November means that Maqeda might actually go home. Though her love is theatre and writing, she helped autistic and dyslexic children as a teaching assistant while studying, and is keen to make use of her knowledge at home. “I had never heard of autism in Zimbabwe,” she says. “I feel that if I went to Zimbabwe, I might make a difference.” This would be in line with Cara’s aims for academics to return if the situation at home improves. For now, with elections round the corner, like many Zimbabweans she is in wait-and-see mode.

Eventually, Mohin Rahman would like to go home too. We peer through lab glass windows and he explains the research he is doing into solar power that could revolutionise energy consumption for a country like Bangladesh. But, apart from his being on a death list, he says the problem is that most Bangladeshis are infused with religion and have no time for science.

Rahman, 28, was not on the death list for being a scientist but for running a blogging platform. He explains how, a decade ago, blogging was a powerful tool in Bangladesh. “As a nation we are very fond of having group chats and having meaningless talk for hours.” The popularity of these forums was such that some posts were read by a million people. “It was a huge community.”

Rahman maintains that his blogs weren’t only focused on politics. “It’s not like we had some special agenda to speak against something. But from the beginnning we were involved in justice activism for the 1971 genocide in Bangladesh.”

Between 2013 and 2015, a number of bloggers were murdered, having called for the perpetrators of the genocide to be brought to justice. Initially, Rahman was not worried as, like many, he used a pseudonym. To this day, he cannot work out how his real identity was rumbled. His university and his landlord beefed up security but all he could do was travel from home to class by car and back again. “I was in agony. I was like, ‘Whatever happens happens, if they kill me, they kill me.’ I kind of gave up. It was a dark phase of my life.”

On the internet he discovered Cara, which found him an academic home at a university in the Midlands. Did he celebrate when he got the news that he had been a thrown a lifeline from his new university? No, he says. He only felt relief. “We were just waiting to step out of the country.”

When Zaher al-Bakour got his British visa from the consulate in Beirut, so he could take up a fellowship in Scotland, he burst into tears. He had begun his masters in Syria, even though there was no money for research. His supervisor was the manager of a pharmaceutical plant, so they did a deal. He would work part-time and do research there. The only catch was that the plant was on the front line on the rebel-held side of the city and what used to be a 15-minute drive was now a 12-hour journey.

The best academics had left the university and it also stopped offering PhDs, so al-Bakour was under pressure. Quite apart from regime jets bombing the plant directly three times for no obvious reason, rebels lobbing adapted gas canisters over the line and hitting his home street, and sniping at the street corner, he would be drafted to fight as soon as he finished his masters. He was desperate to find a way out. In search of a job abroad, he sent out 600 emails to pharmaceutical companies round the world and received only two replies, one of which informed him that they would be keeping his CV on file.

As we talk, he stops for longer and longer pauses. He starts to bite the knuckle of his thumb. I apologise if I am pushing him too hard. He says that sometimes people in the lab ask him if he is OK. He just feels under huge pressure not to waste the money that has been given to him. The things he has lived through are always “alive in my head”, he says. His sister calls again. What it means to be here, quite apart from simple safety, is that he is again on “the front line” but now of research. “I have to do something that no one else has done and so add something to the field.”

In that speech in 1933, Einstein said that “without freedom there would have been no Shakespeare, no Goethe, no Newton, no Faraday, no Pasteur, no Lister”. With the latest figures showing the number of people driven from their homes now at a record 68.5 million, saving academics trapped by war or evil regimes will remain one small but vital drop in the ocean.

Tim Judah is the author of several books on war. His most recent is ‘In Wartime: Stories from Ukraine’

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments