In photos: France makes heavy weather of plugging ‘thermal sieves’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Emmanuel Macron launched his successful bid for France’s presidency more than four years ago, among his pledges was to address the country’s fuel poverty and boost energy efficiency through improved home insulation.

But progress so far has been slow.

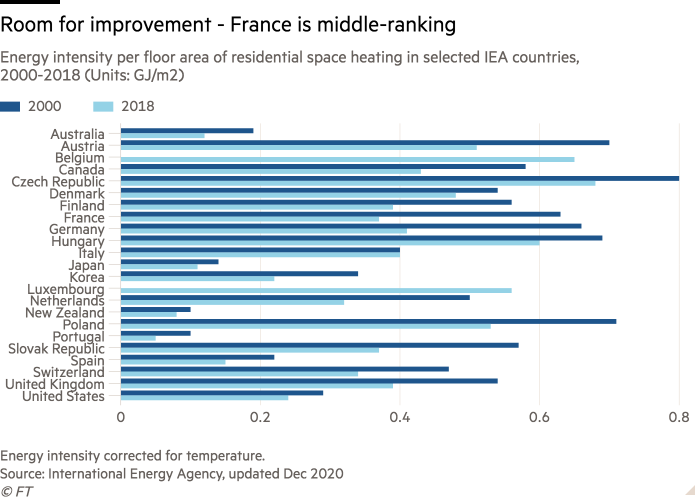

Macron’s promise was an acknowledgment that, despite the country’s commitment to the climate goals agreed in Paris in 2015, France’s own record on cutting energy use by households is not particularly impressive.

At the centre of the debate are what are called passoires thermiques — literally ‘thermal sieves’, a term for dwellings ranked in the two lowest categories of the country’s Energy Performance Certificate scheme, with ratings of “F” and “G”.

These passoires thermiques were estimated to make up nearly 17 per cent of the country’s housing stock in 2018, according to France’s Ecological Transition Ministry. A further 24 per cent were certified with the mediocre rating of “E” — around the same proportion as those in the three highest categories. Properties built before 1948 account for nearly 23 per cent of French housing and almost 70 per cent of them have a rating of “E” or lower.

The problem is particularly acute in cities such as Paris, where many buildings from the Haussmann era of the mid-1800s are subject to protection on architectural grounds but liable to leak heat copiously from doors and windows.

Insulation requirements on new buildings in the city took effect only in 1974. But, even then, planning rules prohibit the modification of exterior facades of protected buildings, requiring insulation to be installed exclusively in interiors.

Macron’s new policy is being driven by a combination of climate protection goals and longstanding concern over energy poverty, seen as an important component of economic deprivation across the country.

According to a report in 2019 by France’s Energy Poverty Observatory, a government-sponsored advisory body, 15 per cent of inhabitants reported suffering from cold for at least 24 hours during the winter of 2017. And 11.6 per cent of the population — mostly among the poorest — said more than 8 per cent of their income went on home energy costs.

A report on France’s progress toward net zero carbon emissions, published last week by the International Energy Agency, praised government plans and funding commitments to encourage building retrofits. The IEA noted that, over the past 20 years, many of the country’s efficiency gains have come from more stringent building codes but renovation rates remain slow.

Since 2017, the Isolation à 1 euro’ scheme has offered poorer households floor or loft insulation through commercial installers with costs reimbursed by the government.

However, the initiative has led to French households being bombarded by phone calls from businesses claiming to provide insulation under the one-euro scheme, many of them from scammers. The economy ministry had to issue a warning to consumers to beware of fraud and ban cold calling by energy renovation providers. The scheme, in its current form, ended at the beginning of July.

Adding to the official embarrassment, the government has been obliged to offer free re-certification to owners of up to 200,000 homes built before 1975 who have received incorrect ratings, including 80,000 categorised as “F” or “G”.

Last year, Macron admitted that the government had been hesitant to adopt more stringent proposals to improve the housing stock. These had included an outright ban on renting out properties in the lowest “F” and “G” energy efficiency categories. But the government feared it would penalise less well-off households and reduce the availability of rental properties.

However, energy efficiency recommendations made by the Citizen Climate Convention, set up by the president in 2019, have been implemented in the government’s Climate and Resilience legislation, which received final approval in August this year. The law sets out a series of measures designed gradually to step up pressure on owners of passoires thermiques.

From 2023, owners of homes classified as “G” will be barred from increasing the rental price of the property unless they take remedial insulation work. If they do not, two years after that, rental will be forbidden. This restriction will be applied in 2028 to homes classified as “F”, and in 2034 to those with an “E” rating. Existing tenants will be able to require the landlord to install insulation to bring the property up to the minimum acceptable standard.

From next year, when single-family homes classified as “F” and “G” are sold, the vendors must commission an energy audit detailing necessary improvements. This obligation will be extended to class “E” in 2025 and “D” in 2034.

All households will have access to state-guaranteed loans to finance some of the cost renovations, although independent estimates suggest that bringing a “G”-rated dwelling up to “D” standard will cost a minimum of €50,000.

These measures are liable to lead to a discount in the sale prices of affected properties, according to Fitch Ratings — although its analysts note that price changes are likely to be gradual since only about 3 per cent of France’s housing stock is sold each year.

Nevertheless, there is already some evidence that owners are seeking to unload energy-guzzling passoires thermique properties (those certified as “E”, “F” or “G”) before the legislation’s rental ban starts to take effect, according to sale and rental online marketplace SeLoger.

It reported in November that listings for sale of homes ranked lowest for energy efficiency had soared in 23 of 40 cities surveyed. In Paris, listings of inefficient properties rose 72 per cent in October compared when with average volumes in the same month the previous year. In Rennes, listings rose 74 per and, in Nantes, by 70 per cent.

Comments