Life’s little pleasures: a mini history of the doll’s house

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In Paris’s Passage Jouffroy there is a shop in which you can buy anything for your house. Furniture, lighting, crockery, Christmas decorations, tableware, houseplants — everything. But all very, very small. Pain d’Epices is a world within a world and reveals a realm of perfectly reduced objects. Whenever I went to Paris I couldn’t resist popping in and browsing though the tiny, perfectly miniaturised cutlery and pots and pans, the working standard lamps and chandeliers and the wine glasses and bottles that require tweezers to pick up. I always bought a little something, though frankly, my girls were never that interested and the accessories were anyway too dainty for their own clunky wooden doll’s house. Yet perhaps that was always the point. These miniature houses might look like toys, but they are really for us, adults able to appreciate the craftsmanship, the accuracy as well as the absurdity of these reproductions.

Dolls’ houses, or “baby houses” as they were originally known, were initially playthings for wealthy adults and used as conversation pieces. The earliest known example was that made for Albert V, Duke of Bavaria in 1557. The Munich Baby House and its successors belonged to the world of the Wunderkammer, the “cabinet of curiosities”. It was more a cabinet than a miniature house, a piece of furniture that concealed its contents but opened up to reveal an interior world of wonder. Albert V was a passionate collector of antiquities and art and this wooden cabinet would have been recognisable as something that contained items of interest, although not of what kind.

The Munich Baby House was lost in a fire in 1674 but a house dating from 1673 is included in a new exhibition at the V&A’s Museum of Childhood in London titled “Small Stories: At Home in a Doll’s House”. The Nuremberg House is a very different object to its predecessor. Albert V was a Catholic and a key figure in a Counter-Reformation which aimed to restore Bavaria’s Catholic tradition and power. The house features a picture of Martin Luther, floating oddly between two windows like a stubborn sticker on a child’s bedroom cupboard.

This is a remarkable object but it is not the Wunderkammer of the Renaissance. Instead, the Nuremberg House is a reproduction of a stone-built townhouse complete with all the accoutrements of everyday life in a well-to-do household. That these houses have survived to this extent is extraordinary. The pewter pots, pans, plates and tankards still hang on the walls alongside the nutmeg grater and a beautifully crafted ceramic corner stove. This intimate and intricate representation of the workings of a household has a dual function: entertainment and education. In common with many later dolls’ houses, this one was almost certainly intended in part as a tool for teaching the complexities of running a household. Most servants at this time would have been illiterate and the house constituted a graphic illustration of the functions, places and rituals of housekeeping.

Dating from about a century later, the British-made Tate Baby House is altogether grander. A brick house with a sweeping operatic stair, it opens to reveal an elaborate interior with an array of exquisitely detailed contents — silk curtains, elaborate four-poster beds, panelled rooms and painted fire screens. Its history echoes that of a real house, with successive generations updating the interiors with newly fashionable fabrics and furniture.

The Killer Cabinet House isn’t quite as dangerous as its name implies. Commissioned by the unfortunately named Manchester surgeon Dr John Egerton Killer in about 1800, it appears as a black lacquer cabinet decorated in Chinoiserie style. It opens, however, to reveal four stylish Regency rooms, also decorated in the light hand-painted Chinese style familiar from the Royal Pavilion in Brighton.

Rather different again is the 1890s Box Back Terrace House. This one is a representation of an everyday, rather than an extraordinary, house. A simple dwelling set over three storeys, it contains solid brown furniture enlivened by a few fashionable touches. Yet this is the doll’s house as middle-class toy rather than plaything of wealthy adults.

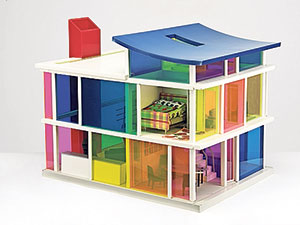

There are many other houses on display, including a grand 1890s version that perfectly represents the crowded clutter of the late Victorian bourgeois interior and a mock Tudor suburban mansion. Then, with the Whiteladies House of 1935, the doll’s house entered the modern age. This deco-moderne dwelling with its sun terrace, murals and pool is a wonderful evocation of the changes that swept through architectural fashion in the modern age. Tubular chairs, geometric designs, a sleek sports car in the garage radically alter the traditional nature of the doll’s house from its densely decorated, cluttered interiors. The same trend is even more discernible in the garishly coloured Kaleidoscope House (2001) with its pop-art transparent plastic walls, and furniture designed by designers such as Ron Arad and Karim Rashid. Yet these modern dolls’ houses also bring up the question of nostalgia.

Modernity occupies a more exalted position in this exhibition than it probably deserves. Although the dolls’ houses of the 18th and 19th centuries may have been designed to show off the fashionable taste of their owners, over the past century or so the history of the doll’s house has been one of nostalgia. The shop in Paris displays the fruits of a late-19th-century bourgeois lifestyle, not the atomised world of a contemporary household. There are no tablets or games consoles. Take a look at the various websites for US or British doll’s-house enthusiasts and they reflect a world that has long disappeared.

That cosy, nostalgic domesticity is, however, at odds with an unsettling sense of a too-real world of reduction. In the remarkable 1957 film The Incredible Shrinking Man, the protagonist finds himself getting smaller each day and ends up living, for a while, in a doll’s house (until the cat chases him out). It is an eerie echo of a childhood fantasy of living vicariously through the tiny contents of an imaginary world.

Artist Rachel Whiteread collects old dolls’ houses, not as antiques but rather as miniaturised simulacra. The suburban houses, cutesy cottages and mini-mansions exude an existential angst of lost childhoods and unloved abandonment. The houses piled into an uneasy, twilit suburb of empty dwellings create a powerful, evocative image. Henrik Ibsen also exploited this sense of unease in the implicit comparison of the life of a wife trapped in a dependent, bourgeois lifestyle to an existence in a doll’s house in the title of his most revered play.

From the Wunderkammer to the favoured toy, the doll’s house delivers a sense of control over an idealised environment. It presented a God’s-eye view with its owner as God, rather than merely inhabitant. For the child it is exactly the same but more so. Children lack the control over their everyday lives so the ability to dictate the details of existence in the doll’s house provides a sense of agency.

The doll’s house has lasted because it allows our adult and our infant selves to imagine a level of perfection, completeness and control so conspicuously lacking from the chaos of our actual lives.

‘Small Stories: At Home in a Doll’s House’ opens this weekend at the V&A’s Museum of Childhood in London, and runs until September 6 2015; museumofchildhood.org.uk

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture critic

Photographs: Courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum

Comments