What next for the rich in a post-pandemic world?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

What next for the world’s rich? They have managed to maintain or even enhance their fortunes during the pandemic. Will they do well in the recovery too?

Credit Suisse thinks so. The Swiss bank’s 2021 global wealth report forecasts that the world’s wealth stocks — including financial and non-financial assets, such as property — will grow by 39 per cent over the next five years, reaching $583tn by 2025.

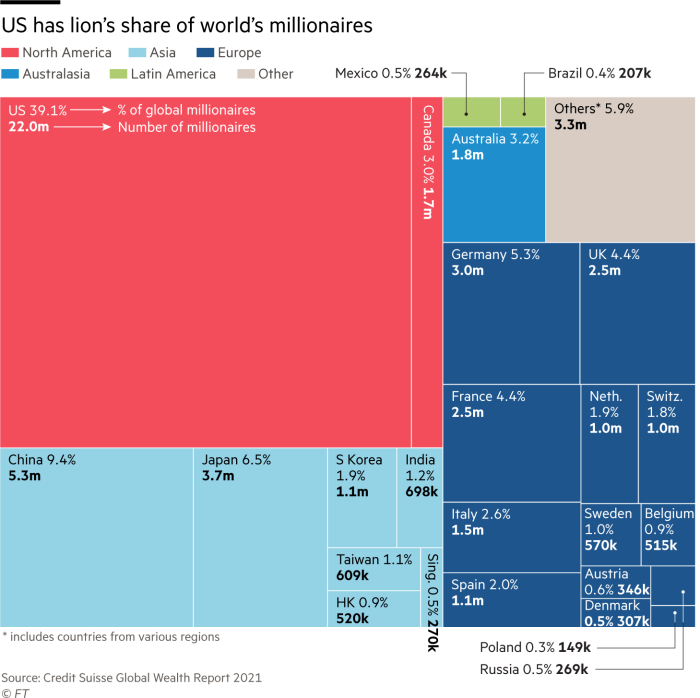

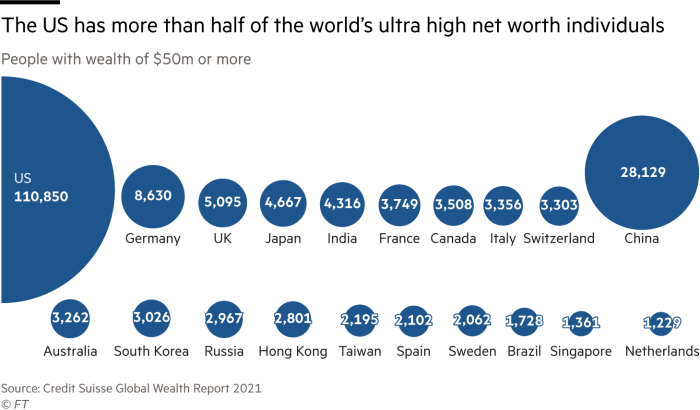

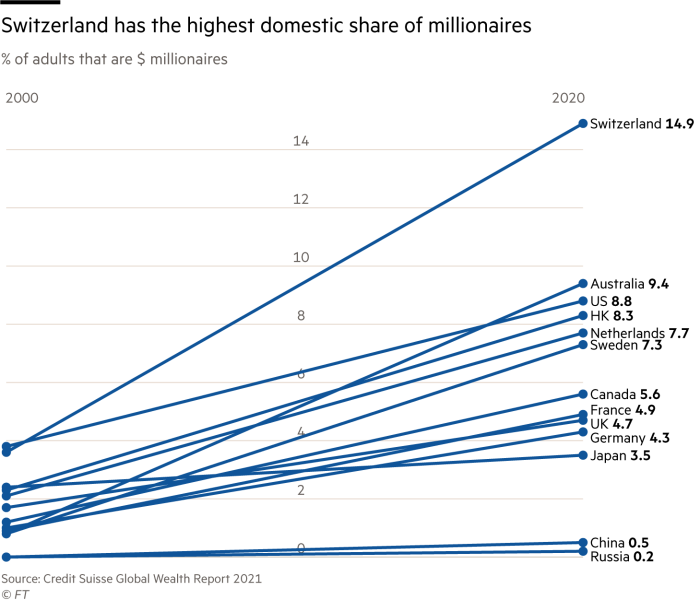

The number of millionaires is predicted to grow even faster, by 50 per cent, from 56.1m at the end of last year to 84m. And the number of super-millionaires — ultra-high net worth individuals with $50m or more to their name — will jump from 215,000 to 344,000, a rise of 60 per cent.

These predictions are based on the widely held assumption, shared by the IMF, that the global economy is set for robust post-pandemic recovery, with an increase in GDP of 6 per cent this year alone. So, even if the financial markets don’t deliver a further boost to wealth, economic growth may reasonably be expected to do so.

While the US will remain the richest country in terms of household wealth, the biggest increases will come from China and India, where people are accumulating wealth at unprecedented rates. By 2025, China’s household wealth will equal the US’s for 2017, says Credit Suisse.

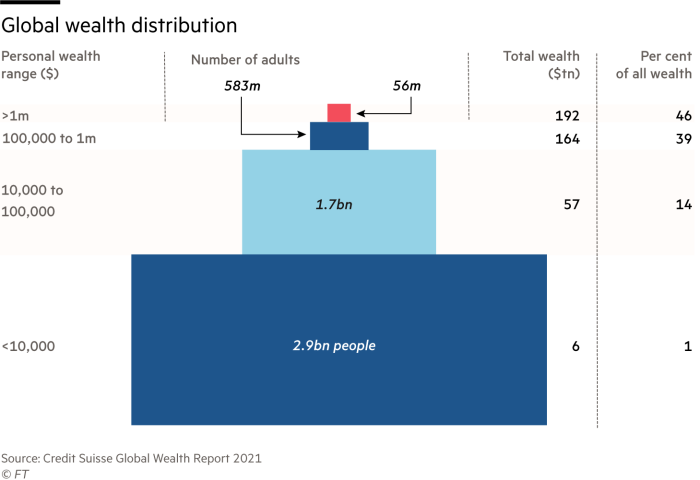

That all sounds very comforting for the fortunate rich. But it’s not the whole story. As the Swiss bank also highlights, this wealth accumulation coincides with persistent wealth inequality. Rich people did not get richer last year because they were smarter on average than others — they got richer primarily because asset prices were boosted by anti-pandemic policies from governments and central banks, chiefly ultra-low interest rates. “If asset price increases are set aside, then global household wealth may well have fallen,” the bank notes.

By contrast, poorer people suffered the brunt of the pandemic’s economic damage, losing their jobs, seeing pay cut and, often, being forced to run down their meagre savings.

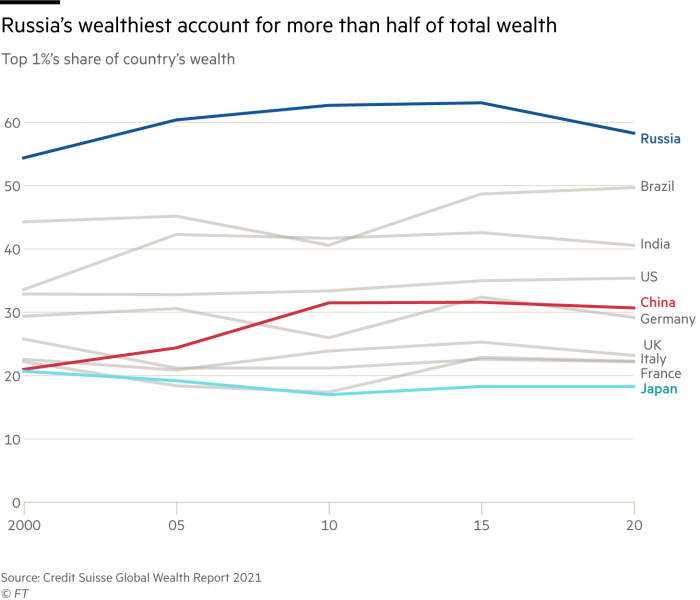

The overall level of inequality remains below levels recorded before 2016 but it has risen in many countries, says Credit Suisse. If even a bank specialising in wealthy customers is concerned about inequality, then inequality is a problem that needs addressing.

Fortunately, at a global level, inequality between countries is declining, principally due to the rise of China, which is helping to close the gap in income and wealth between developed and developing nations. But inequality within countries is more intractable, as it involves differences of income, wealth, education and even health — as the pandemic has highlighted.

Governments are acutely aware of the challenge, with US president Joe Biden proposing an economic programme that includes tax increases for the rich, including higher capital gains taxes and a tougher inheritance tax regime. There is renewed debate over wealth taxes: in Britain, the independent Wealth Tax Commission has recommended a one-off 1 per cent wealth tax on households with more than £1m.

But there’s little appetite for radical changes in tax policy. The priorities are fighting the pandemic and boosting economic recovery, followed, at some distance, by shoring up the public finances. As far as inequality is concerned, the focus is on investing more public money in deprived regions and districts, as with the White House’s infrastructure spending proposals or the UK’s “levelling up” agenda.

Better education, healthcare and transport can all help improve people’s lives. But it’s unlikely to do much in the short term to reduce the glaring gaps in income and wealth between the rich and the rest.

Stefan Wagstyl is editor, FT Wealth and FT Money. Follow Stefan on Twitter

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments