Buyer beware: Chinese shoppers’ weapon to dodge cheap knock-offs

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A man in his twenties sporting a shiny black suit and tie looks into the camera. Behind him a slideshow of purses imprinted with Louis Vuitton logos plays. “The second image shows the colour of the protective film on the zip. If it is authentic, it should be light blue,” he tells the viewer.

The presenter is Yan Chuang and his videos have been viewed more than 100m times in China. In a country renowned for counterfeiting, Mr Chuang is a new kind of protagonist in the fight against fakes: a professional authenticator.

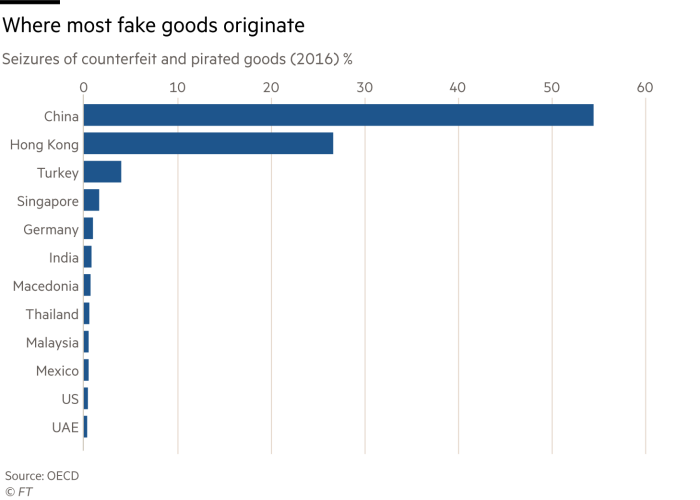

China has a reputation for being the Wild West of fakes for a reason: a US consumer watchdog group, for instance, estimates 80 per cent of the world’s counterfeit goods come from the Middle Kingdom. China’s authentication industry is born out of a counterfeit goods market that the OECD’s most recent data from 2013 suggests is worth $461bn globally, about 2.5 per cent of all world trade.

Meanwhile, the country’s emerging consumer class has caught the attention of luxury brands, which are expanding their presence in the market. Mainland Chinese shoppers spent more than €105bn ($121bn) on luxury items including watches and jewellery in 2017, according to Boston Consulting Group, accounting for 32 per cent of the worldwide total.

More and more of these products are being bought and sold through ecommerce channels and, while a boon for both the technology industry and consumer choice, it has also made it easier for those making and selling cheap knock-offs to flit between platforms to avoid detection.

Social trust around consumer goods in China is already low. The most notorious example of shoppers being duped was the 2008 milk scandal, where 300,000 infants were made sick by baby formula containing a chemical to give the appearance of a higher protein content. Six babies died, and consumer confidence surrounding branded goods has yet to fully recover.

It is against this backdrop that companies offering to authenticate luxury goods are carving out a market.

Using an authenticator service is easy. One app, Luxury Fashion (or Isheyipai), boasts an “expert jury” of 12 authenticators. It asks the user to upload a photograph of the item, the brand name and choose whom they want to check their product. Prices range from Rmb49 (£5.50) for a junior authenticator to Rmb99 for senior staff. Appraisers each have areas of expertise, such as bags, jewellery or trainers, and the app states that they all trained in either China, Japan or the US.

The first companies and courses offering professional authentication started appearing in 2014 and there are now more than a dozen apps offering to verify luxury goods on the Chinese Apple iOS app store.

This has led to greater demand for experts: private companies clustered in east coast cities offer 10-day training courses that can cost Rmb20,000-Rmb40,000 (£2,250-£4,500). These programmes teach student appraisers how to inspect a wide range of luxury brands and products, with advice about texture, logos, stitching and everything else that a counterfeiter might get wrong.

Training in China does not currently offer the legal or professional status seen in Japan, where only licensed platforms can legally buy and sell pre-owned luxury items.

Authentication company Zhiduoshao was launched in 2017 and it says it has hundreds of thousands of users who pay Rmb49 each time they want a product to be checked by an expert.

Zhiduoshao (which means “how much is it”) says that many of its more experienced authenticators trained in Japan and pass their skills on to new recruits — but years of experience are what really matters, they say. Terry Lee, an operations manager at Zhiduoshao. “We’re here to help the user identify what’s real and what isn’t.”

The technical intricacies of watches and jewellery items, many of which can be hidden inside the product, bring an another layer of difficulty to authenticating items remotely.

“For our process, the image [of the watch] is just the first level,” explains Lee Bingle, associate vice-president of corporate communications for Christie’s Asia, an auctioneer. “We always inspect in person as well, and open up the inside and check.”

Yet authentication is still something that some luxury brands and sellers value highly.

Vestiaire Collective, a global platform for pre-owned designer goods that operates out of Hong Kong, employs a team of in-house authenticators from the fashion industry, luxury and auction houses, according to co-founders Fanny Moizant and Sophie Hersan. “There are always new styles coming into the market [so] you need to have a strong background working in authenticity but you also always need to keep learning,” they say.

Other second-hand luxury goods platforms, such as the Alibaba-owned Xian Yu, provide similar authentication services to the likes of Zhiduoshao and Luxury Fashion, in the hope that potential sellers will then list goods on their platforms.

In an ironic twist, China’s relentlessly opportunistic counterfeiters are now imitating these authenticators, too.

Adam Knight, co-founder of China-focused brand agency Tong Digital, points to a case where “consumers discovered that the [authentication] platform was itself guilty of faking reviews and authentications in order to sell fake goods”.

Elsewhere, Chinese media has reported stories where daigou — agents who travel overseas on behalf of buyers to buy products at lower prices — had colluded with unscrupulous authentication companies to produce fake certifications.

China’s government has struggled to get a handle on fakes. The country’s first ecommerce law, which took effect on January 1 this year, aims to discourage counterfeiting through heavier fines and it places more responsibility on digital platforms to remove sellers of fakes. State media regularly publishes photographs of the latest swoops on counterfeit dealers to demonstrate that China is actively cracking down on it.

Growth in China’s second-hand luxury goods market is also creating new inroads for fraudsters. “The second-hand luxury market in China is really hot right now,” says Zhiduoshao’s Mr Lee.

The emergence of authentication companies has been fuelled by consumer anxieties, according Mr Knight. Authentication can be used as a way to prove to friends that a recent purchase is worthy of their admiration.

“When every man and his dog can own a Gucci-branded handbag, how do you differentiate yourself? By having a Gucci-authenticated handbag,” Mr Knight says.

Some argue, however, that consumers are savvy enough to navigate the online market without help. “There isn’t a huge demand or need for the third-party authentication companies,” believes Ann Bierbower, senior account manager at China Luxury Advisors, a consultancy that works with high-end brands on consumer strategy.

She says shoppers are more likely to do their own research and rely on recommendations from friends when using online platforms — indeed, 16 of 22 online buyers of luxury goods that the Financial Times interviewed for this article were unaware of authentication companies.

But when in 2017 an Alibaba-owned ecommerce platform, Taobao, was found to have 240,000 vendors selling fake goods, and another, Pinduoduo, was forced to remove more than 10m fake items from its site, it is easy to see why some consumers are looking for reassurance.

“There are a lot of A-huo [high-quality fake] right now. It’s really hard to tell,” says a finance worker in Shenzhen, who asked to remain anonymous. She frequently buys designer goods through daigou.

This method is not foolproof, however: she recently pulled out of buying a necklace that her agent said was Swarovski because an invoice and guarantee certificate could not be provided. She says online authentication agencies are a last resort when her own savvy is not enough.

Authentication companies have an uneasy relationship with the brands whose integrity they claim to protect.

No major label has come forward to indicate they support the work of authenticators. Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Omega and Burberry all declined to comment for this article. Cartier said only that their products should be bought from “authorised boutiques”. Audemars Piguet says it does not endorse any authentication app and De Beers says it is unaware of them.

“We would encourage any person purchasing De Beers branded jewellery online or second hand from a third party, to have them verified in one of our authorised stores to confirm that they are genuine,” a spokesperson says.

Though some brands give little attention to third-party authenticators, many of these platforms use luxury brands’ logos prominently on their apps and websites, which could lead to a stand-off between parties.

Eugene Low, an intellectual property lawyer at Hogan Lovells in Hong Kong, says that while such companies can help consumers, there are potential risks.

“If these authentication services make wrong or misleading claims, for example claiming false association with a brand, then they may fall foul of unfair competition activities,” he says.

It is also unclear whether third-party authenticators would be willing or able to pass evidence of counterfeiting on to trademark holders or the Chinese authorities: Zhiduoshao’s Mr Lee says that would not be obliged to report any evidence of wrongdoing his company obtains, nor would it be legally binding.

The ambiguous legal status has enabled imitation authenticator companies to exploit the reputation of more established incumbents. Zhiduoshao, for instance, has complained of websites using similar names, layouts and images to its own.

In some cases, China’s authentication apps have profited from the same powers of deception as the artisans of fake watches and jewellery, using imitation or fraudulent branding to embellish their profile.

Zhiduoshao is recognised by the China Consumer Rights Protection Associationand provides a guide on how to spot a so-called fake authenticator. One warning sign, Zhiduoshao says, is if a company is not suitably “rigorous” on criteria when requesting a photograph of a product.

While Chinese consumers’ aspiration for luxury goods has grown and stores are popping up outside of the major cities, many shoppers remain unwilling to pay retail prices.

The concept of buying second-hand designer goods is relatively new in China — accounting for only 3 per cent of the luxury market — but industry observers have forecast rapid growth. The potential appeal of authenticators among consumers in this expanding niche is high.

“Chinese people have a lot of experience when it comes to fake goods,” says Ma Ke, a photographer who works in Beijing and is wary of unscrupulous sellers. He says he would be “really worried and angry” if he accidentally bought a fake product but is happy to continue buying second-hand goods.

To appeal to shoppers like Ma Ke, some brands have formed partnerships with online stores like Tmall, a company once known solely for its heavily discounted goods. This move is “not necessarily to drive [brand] sales”, believes Jonathan Smith, chief executive of strategic consultancy Hot Pot China, “but to ensure the two can work together to take down fakes from the marketplace ecosystem”.

In the fight against counterfeiting, brands, online retailers and the government are beginning to work more closely on their strategies to reform China’s reputation as the land of cheap knock-offs.

Yet despite authenticators sharing an anti-fakes mission with the luxury goods industry, the space for companies that focus solely on this area may be limited.

Third-party services could struggle to build credibility if brands continue to distance themselves from them, and could face legal action if they mislead consumers. Prospects might be better for the individuals who train as authenticators, however: they could join mainstream online selling platforms, work in-house at luxury brands or even in government, as organisations ramp up the number of personnel who can appraise products.

The authentication business depends on legitimacy. If this nascent sector can see off its own imitators, it could yet earn brands’ seal of approval.

Comments