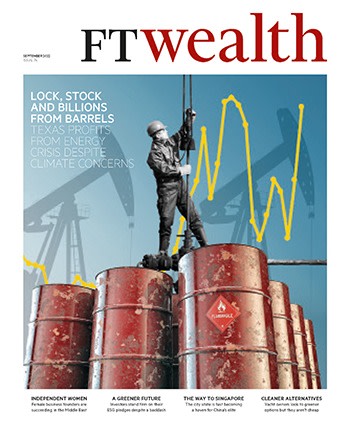

Early investors in Texas oilfields strike lucky

Simply sign up to the Oil & Gas industry myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Cody Campbell calls his rapid rise in America’s hardscrabble oil patch a “wild ride”.

Little more than a decade ago, when Campbell was in his late 20s, he was looking for his next act. Injury had cut short a brief professional American football career and the 2008 housing crisis had driven him out of the real estate business. It was then that he returned from Indiana to his native Texas and teamed up with a friend, John Sellers, to start buying up drilling rights in promising oilfields to “try to make a little money”.

Neither men had much experience in America’s fiercely competitive oil business when they started. But Campbell, now 40 years old, says his stint in real estate helped as they acquired their first land for drilling. “We didn’t have any money. We didn’t have any employees. It was just the two of us. And there were a number of times where we sort of bet it all on individual projects. Somehow it worked out,” he says.

In fact, it worked out better than Campbell could have imagined. Through his firm Double Eagle Energy, the company he jointly owns with Sellers, he has amassed a fortune over the past decade selling oil-producing operations to bigger players. Those deals now total nearly $10bn, making Campbell one of the Texas oil patch’s most prolific dealmakers of recent years.

His breakthrough sale came in 2012, when he sold a cluster of oil and gas wells in Oklahoma for $250mn to the late wildcatter Aubrey McClendon, who co-founded and ran Chesapeake Energy, the large energy group.

The deals have only grown since. Most recently, in 2021, he and his partners, who now include private equity company Apollo Global Management, sold a business in the Permian basin in Texas, one of the world’s largest oilfields, to oil company Pioneer Natural Resources for $6.4bn. That came on the heels of a $2.8bn sale in the same area in 2017 to Parsley Energy, an oil and gas producer, itself later bought by Pioneer Resources. “It’s been a wild ride, going from basically just a bootstrap operation, where we never knew from week to week whether we were going to make it, to doing multibillion-dollar transactions,” says Campbell.

Campbell, like others in the Texan oil industry, has been investing — and taking profits — despite mounting global concerns about the impact of fossil fuel emissions on climate change. They have ploughed on even as these worries combined with growing political pressure have pushed many financial investors to reduce their commitment to the industry — and even pull out altogether.

In the US, the Biden administration has cheered passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the biggest climate bill in the nation’s history, which will channel $370bn into clean energy and electric vehicles over the next decade, with the aim of slashing fossil fuel consumption.

President Joe Biden, who once promised to transition America “away from the oil industry”, called the bill the “largest investment ever in combating the existential crisis of climate change”.

At times, in the years Campbell was making his fortune, it seemed that sharp drops in oil prices would help climate campaigners by driving down fossil fuel production — notably at the outbreak of the Covid pandemic in 2020. The consequent lockdowns saw US oil prices even briefly falling below zero, hitting a negative $37.6 a barrel, as world demand suddenly dried up. Hundreds of oil companies in Texas and across the US went out of business, and it was a close-run thing for many more.

Campbell says he and his partners discussed “shutting everything down” at one point during the pandemic but ultimately decided to stick to their original plans. “It was tough for everybody and we were no different, it was real stressful,” he says of the period.

But, in the volatile markets that rule the industry, prices have since bounced back dramatically. They were already on the rise throughout 2021 as global demand, driven by economic recovery, was growing faster than producers could bring back supply.

Then, in February this year, Russia sent its tanks into Ukraine. The war brought havoc to commodity markets and accelerated the surge in global crude prices, which rose to $129/b in March, the highest level since 2008. Though they have since fallen back to around $100/b, prices remain far above the $64/b average for 2019.

In Texas, this surge has delivered a bonanza to those, such as Campbell, that have invested in the shale revolution. Big publicly listed US shale oil producers such as Pioneer, Devon Energy and ConocoPhillips, proxies for the rest of the shale industry, are making more cash than ever before.

Political pressure on the production and use of fossil fuel looms as large as ever, as highlighted by the Inflation Reduction Act. But the industry is not short of support in the US, especially in the Republican party, which dominates Texas. In the summer of 2020, Campbell had an unexpected call from the White House. President Donald Trump, who would go on to lose the election that autumn, decided to visit one of Double Eagle’s operations in Midland, Texas, to signal support for the domestic oil and gas industry.

The ex-president was, and is, hugely popular in oil country, where “Make America Great Again” flags fly and “Trump 2024” bumper stickers are plastered on the back of pick-up trucks. “His support for the industry was really critical through that period,” says Campbell of the man, who he spent the day with.

As for the outlook now, Campbell says that the high oil prices seen this year — which he argues were exacerbated, but not caused, by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — are a sign of things to come.

Companies face difficulties raising funds to develop new oil and gas projects as banks and other investors shy away from the industry over climate concerns, argues Campbell. He says that the oil supply picture in the coming years “looks very bleak” and he expects it to lead to relatively high prices for the foreseeable future — which would be a financial boon to producers. “I keep thinking that the capital is going to come back with the high prices, but it just seems like people are really hesitant to get back in,” he says.

Billionaire oilman Tim Dunn also remains committed to fossil fuels. A Texan, born and bred, he has been in the industry since the 1970s and founded CrownQuest Operating, based in Midland, Texas, in the mid-1990s. A well-known Republican, he has used his oil wealth to back rightwing Republican candidates in Texas and advance conservative and evangelical Christian causes.

Dunn’s company, like the rest of the industry, was transformed when new shale drilling and fracking technologies helped unlock vast crude reserves in the oilfields of west Texas, where his group owned vast swaths of land that had been deemed too expensive to produce. The huge Permian basin has turned from a dying oilfield into a juggernaut on global energy markets.

Dunn has expanded the business, where he employs two of his sons, Luke and Lee as vice presidents, rapidly in recent years. It is one of the most active oil and gas drillers in Texas and operates more than 1,400 wells, turning out more than 115,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day of oil and gas. CrownQuest ploughed more than $700mn into developing new wells in 2021 alone.

Analysts and bankers say CrownQuest, which is privately held, is among the most coveted Permian drillers among the larger companies that look for acquisitions in the area, though Dunn has resisted selling so far. While the company keeps its finances under wraps, analysts say a sale could command $5bn or more. Dunn credits a focus on “managing risks” in a relentlessly turbulent business for the success. “I think that is one reason we have survived and prospered through exceedingly choppy waters,” he says.

For Dunn, this year’s surging prices has added fuel to his firm’s swift growth. The company, which already produces more from the Permian’s oilfields than US supermajors ExxonMobil and Chevron, says it expects “significant production growth” in the coming years.

Meanwhile, for Campbell, the price upswing has allowed his latest start-up in the Permian to take advantage of a strong tailwind. In June, his Double Eagle raised more than $1.7bn from private equity firms including Apollo and Encap, along with other investors, to start snapping up more development land in the Permian oilfield.

The fundraising success came despite the dearth of capital in the industry. “We’re in growth mode and we have access to capital,” says Campbell of the new venture. He says he’s hunting for bigger acquisitions in Texan oilfields this time round and has assembled a group of investors that can quickly pull off big transactions. The group is ready even for a $5bn deal, he says: “We’re just getting started.”

The acquisition intent is a big bet that the industry will keep making money despite the government-backed moves around the world to cut emissions and reduce the potentially disastrous effects of climate change.

The International Energy Agency predicted in a landmark report last year that spending on exploring for new oil and gas reserves would have to end now for the global economy to hit a target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

That said, its base forecasts still see fossil fuel demand extending far into the future. And this year’s energy crisis, driving fears of fuel shortages, has scrambled the climate debate.

Politicians and consumers, spooked by high energy prices, have shifted their near-term focus from emissions reductions to securing energy supplies — even if they are fossil fuels. Despite the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, President Biden has this year asked the domestic oil industry to increase supply to help bring down high fuel prices at the pump, even if it means higher emissions. In Europe, some leaders now want to soften climate targets.

Hallie Templeton, US-based legal director at Friends of the Earth, an environmental group, slams the Biden administration and the oil and gas industry for continuing to expand oil output in the face of the climate threat. “Biden needs to remove his oil-tinted glasses and start treating oil and gas development with the extreme caution it deserves,” she says.

Some of the oil industry’s biggest players have started eyeing a shift to cleaner fuels. BP, Shell and TotalEnergies are ploughing money into solar projects, offshore wind farms, batteries and electric vehicle charging networks. Even the American oil supermajors ExxonMobil and Chevron, seen as more reticent to abandon oil and gas, are investing in carbon capture and storage and hydrogen to try to cut their emissions and safeguard their businesses from the energy transition.

Campbell argues that the energy crisis that has roiled the global economy this year is a warning sign if leaders try to pull out of fossil fuels too quickly.

“I’m young, and I have a young family, and I worry about [climate change] too. But I think that there’s just a physical reality in the world that we need oil and we need natural gas. We’re seeing right now some of what happens if we don’t have it,” he says

Dunn is more scathing of policymakers’ approach to climate change, which he argues is being used as cover to extend the reach of government power. He argues they are rushing too fast to get the world off fossil fuels, which he says remains central to global wealth and wellbeing. Rather than focus on eliminating oil and gas, policymakers should balance the “economic trade-offs” of cutting fossil fuel use and the potential harm from climate change. In short, they should focus on adapting to a warmer world rather than try to prevent it.

“Only forced impoverishment can deliver us to a 100 per cent renewable future any time soon. Perhaps we should allow policymakers to first convert to this lifestyle and give us a full report on whether they prefer to continue in it,” says Dunn.

Climate activists argue that the rapid drop in the cost of renewables and the risk of climate catastrophe mean a quick transition to cleaner energy is both needed and will ultimately be cheaper than running the global economy on fossil fuels. Yet, from the Texas oilfields, that transition looks a distant prospect.

Of oil, Campbell says, “When my kids have kids, I don’t know. But certainly, for the next couple of decades, for the rest of my career, it’s going be something that we need.”

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments