Beam Suntory: A volatile Japanese-US blend

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Just months after Suntory’s $16bn takeover of US spirits maker Beam in 2014, the chief executive of the Japanese whisky group dropped a bombshell. The quality of the Kentucky-made Jim Beam bourbon could be improved, he suggested, if its distillers employed a Japanese process called kaizen. Matt Shattock, the chief executive of Beam, cringed at the proposal made by his counterpart, Takeshi Niinami. It was seen as a direct affront to the formula perfected by the Jim Beam family over two centuries.

The Suntory chief was suggesting only minor tweaks to the water purification process, not a change to the Beam recipe. But the mere hint of meddling, raised during a board meeting, caused damage. It strained relations just as the two sides were wrestling with how to make a success of the collaboration between the US bourbon maker and its Japanese owner, known for its Yamazaki and Hakushu whiskies. The tensions continued for months with Mr Niinami, on more than one occasion, slamming his fist on a table and walking out of talks in frustration, according to people briefed about the meetings.

“At that stage, everyone was kind of on the edge of their seat trying to understand what exactly is going to happen,” a person involved in the integration process says. “They heard words [from Niinami] like Jim Beam and quality.”

The clash over the art of making spirits, for which Suntory has adopted the Japanese term monozukuri more widely used for manufacturing, laid bare the challenge faced by the chief executives in integrating two proud cultures, each with a strong heritage.

The difficulties highlight the pitfalls that have paralysed many Japanese owners faced with running newly acquired overseas companies. The deal also serves as a wake-up call for smaller players as groups such as AB InBev and SABMiller combine forces to stay competitive in a rapidly consolidating drinks industry.

“How to blend the skill and expertise of both [companies] is our goal. That has been a big challenge but over one and a half years, they more or less commute to each spot: Kentucky and Yamazaki (distilleries). This is a new plan for our integration,” Mr Niinami says.

This blending helped to lift sales at Beam through joint products and marketing. It also went some way towards rescuing a deal that was undermined from the start by broken promises, a lack of governance and unrealistic ambitions, according to interviews with executives and others involved.

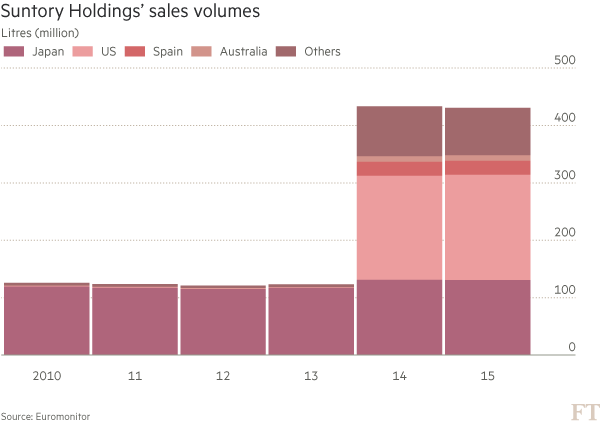

Suntory’s costly acquisition of Beam, an Illinois-based distiller of Maker’s Mark whisky and Courvoisier cognac, was driven by the same motivation that has led to a recent binge in overseas spending by Japanese companies trying to survive a shrinking home market.

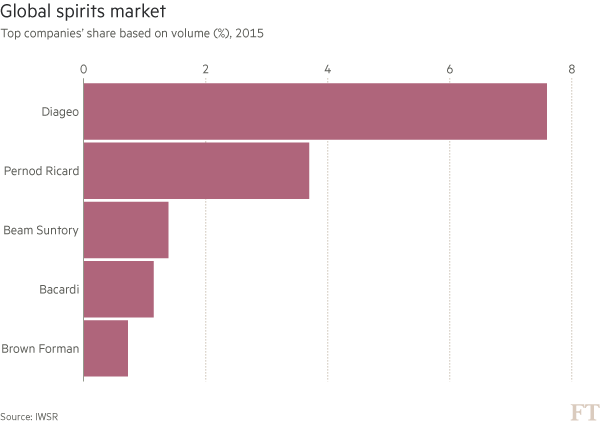

The deal gave the privately held Japanese group a ticket into the US spirits market — the world’s most profitable and one of the few that is still growing. It catapulted Suntory Holdings, Japan’s largest drinks group, into third place in the international spirits industry by volume — after Diageo in the UK and Pernod Ricard in France, according to International Wine and Spirit Research.

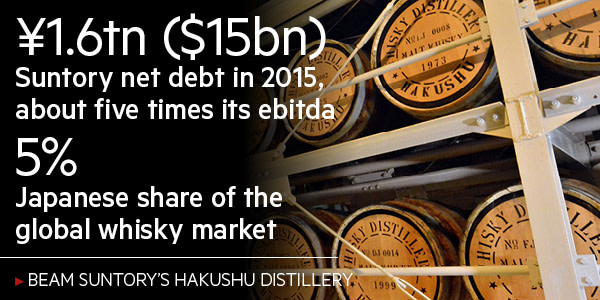

But the gamble came at a huge cost. Suntory emerged from it with net debt at about ¥1.6tn ($15bn), some five times its earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation.

“Beam’s profitability remains high but the speed of debt reduction has been slower than expected,” says Motoki Yanase, analyst at Moody’s. “The group is restricted from aggressively expanding as Suntory management . . . focuses on integration.”

Breaking traditions

Mr Niinami is the company’s first chief executive appointed from outside the founding family. Recruited in October 2014 by Nobutada Saji, the charismatic chairman of Suntory Holdings and the grandson of founder Shinjiro Torii, it represented a bold break with tradition.

The Beam deal was part of a wider expansion. Suntory paid $3.8bn for Orangina Schweppes in 2009, then Mr Saji stepped up his overseas drive after his plan to merge Suntory with Kirin, Japan’s second-biggest brewer, collapsed in 2010. In 2013, the group raised almost $4bn by listing its non-alcoholic drinks and food business, and acquired the Lucozade and Ribena brands from GlaxoSmithKline for £1.35bn.

Mr Saji turned to Harvard-educated Mr Niinami to execute the fraught integration with Beam. Mr Niinami, 57, had earned a reputation as an effective operator in 12 years at the helm of Lawson, Japan’s second-biggest convenience store chain. Fluent in English, he is one of the most internationally minded executives and has close ties to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

He has taken a far more active approach than other Japanese executives involved in foreign takeovers. Suntory has representation on Beam’s audit committee and has a say in its compensation and nomination issues.

“It wasn’t clear who was in control. I told Matt [Shattock, now Beam Suntory chief executive] that I am the boss of the entire Suntory Holdings,” Mr Niinami says.

In the first year, Beam executives were overwhelmed by the rigorous monthly reporting required by Suntory management, particularly on its cash generation. Beam has exceeded the sales and profit targets set at the time of the acquisition, but its Japanese owner pushed it to try harder.

“Suntory has a very hands-on style so there are detailed questions even in board meetings. It may have been to a point where Matt [Shattock] wondered why we wanted to know such detail,” says Shinichiro Hizuka, Suntory’s chief financial officer. “But as we discussed what was behind the numbers, our understanding of their strategy and markets deepened.”

Beyond the practical challenges, a climate of mistrust developed when two pieces of the original post-merger plan were dropped. When the deal was initially discussed, the Japanese side had indicated to Beam that its shares would be relisted in the US. Beam executives had also expected Suntory to sell its Japanese whisky in the US market following the deal.

The Suntory board agreed in the spring of 2014 that it would trigger Beam’s initial public offering within three years of the merger, with the proceeds forming the backbone of the group’s debt repayment plans, according to one person with knowledge of the decision. But the listing was put on hold due to opposition from Suntory Holdings’ founding family, which holds an 89 per cent stake in the group through an asset management firm — upsetting Beam executives who had been promised an IPO.

Under new management

Since the deal, most of the original Beam management team has left, with the exception of Mr Shattock. “Losing the head of international, the US, chief marketing officer, production, human resources and CFO cannot happen without some impact,” says Donard Gaynor, a retired senior executive at Beam who is a consultant to the industry. “This is what makes acquisitions so difficult.”

The high turnover of senior executives was blamed on everything from rival offers to the cancellation of the IPO but Mr Shattock insists the overall turnover rate at Beam — which employs 3,400 people — is at its lowest in three years. “They realise that this investment is made for a very long term and therefore they now have a parent and a home which will be here for many, many years to come,” he says.

In late 2014 Mr Niinami sought to combine the skills of the Jim Beam distillery in Kentucky and Suntory’s Yamazaki distillery, the birthplace of Japanese whisky on the outskirts of Kyoto, to boost the Jim Beam products amid a shortage of Japanese whisky to sell in to the US. To do this Suntory introduced the concept of kaizen, the philosophy of continuous improvement. For workers at Beam, this sounded like criticism of their long-established practices.

“Initially, the interactions were perceived as highly insulting, until we reached mutual understanding regarding culture and intention,” says Vincent Ambrosino, Beam’s former chief financial officer who moved to Tokyo to serve as a senior adviser to Mr Niinami and Mr Hizuka. “Eventually, we figured out that we shared a common objective.”

Teams led by Fred Noe, the master distiller and great grandson of Jim Beam, and Suntory’s chief blender Shinji Fukuyo shuttled between Kentucky and Yamazaki developing new products. Similar collaborations were made in procurement, marketing and risk management. From Beam, Suntory learnt how to manage global operations.

At home, Mr Niinami was fighting a different battle. Before his appointment, the company decided to put its Japanese whisky business under Beam’s management. For some Japanese employees, it felt humiliating to report on domestic operations to a foreign company, especially one that it owned.

Mr Hizuka admits that tensions persist, but adds: “If we are going to sell Suntory’s whiskies worldwide, it would definitely be better to use Beam’s network and branding than to do it all from the Japanese side.”

Suntory’s transition into a global company moved slowly despite Mr Saji’s aspirations. “It’s impossible for everyone to suddenly have a global mindset. That will take three to five years,” Mr Hizuka says. “To be blunt, most of the people in this building see Beam as someone else’s problem.”

Company executives and analysts admit there is no time to waste, however: “The longer it takes to align corporate culture and get effective strategies in place, the more opportunities are missed,” says Stephen Rannekleiv, spirits industry analyst at Rabobank.

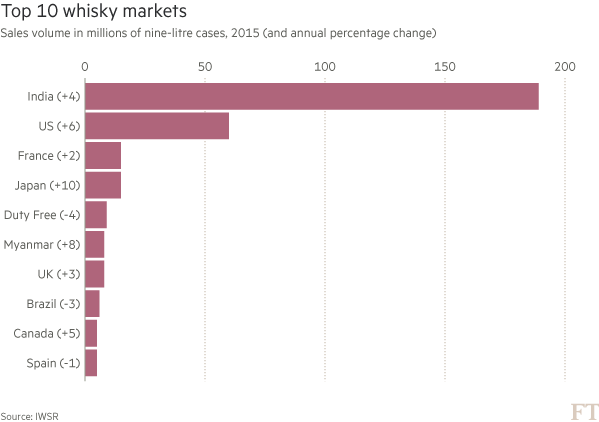

Even after the acquisition of Beam, analysts point to the narrow geographic scope of the two companies as a disadvantage as they seek to tap new markets. In 2015, the group generated 73 per cent of its sales by volume in the US and Japan. But with the Beam deal, the Japanese group will aim to expand sales of brown spirits in India and other parts of Asia.

“They have a lot of catching up to do,” says Jeremy Cunnington, an analyst at Euromonitor. “But the scope for doing [more] investment is a lot more limited with its high level of debt.”

Growing American market

With Beam’s IPO on hold, the group has taken steps to free up cash. It is drawing greater profit margins by selling more high-end products, cutting back on costs, including overseas travel and urging employees to trim working hours. In the past year, Beam has sold its Spanish brandy and sherry business while Suntory offloaded its stakes in hamburger chain First-Kitchen and sandwich franchise Subway in Japan.

The focus on the US and Japan has benefited Suntory and Beam as rivals such as Jack Daniel’s owner Brown-Forman and Diageo grapple with a slowdown in emerging markets.

By volume, whisky sales in the US — where the combined group holds a 19 per cent market share according to Euromonitor — and Japan were up 6.5 per cent and 9.8 per cent respectively, while markets in China and Brazil declined, according to IWSR.

Suntory Holdings saw its net profit rise 18 per cent to ¥45.2bn in 2015 while robust Beam sales lifted the group’s revenue by 9 per cent to ¥2.7tn.

In September, Beam Suntory will move its global headquarters to downtown Chicago from suburban Deerfield, as part of the group’s push to ramp up marketing in big cities where it sees fierce competition for millennials and other young drinkers of premium bourbon and whisky.

“Everyone is rushing to the US, from Diageo to Pernod,” says Mr Niinami. “That’s a big threat.”

Comments