Three parties: Democrats, Republicans and mayors

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Last month a panel of mayors from leading US cities and beyond discussed the challenges facing urban leaders during the coronavirus pandemic, at a virtual event held by the Pritzker forum on global cities on Thursday 15 October, with the FT as media partner.

Below are edited Q&A highlights from two discussions with FT editors.

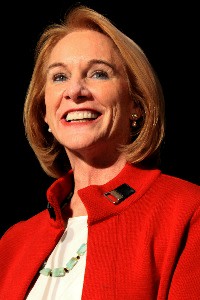

First, a session with the mayors of Seattle, Miami and Pittsburgh, moderated by Gillian Tett, US editor at large.

Jenny Durkan, mayor of Seattle (JD): This has been the most challenging time, I think, for mayors across America. We are the front lines, and we were the first to see Covid in the Seattle area. And when we discovered that we had [it] in the community, we had no federal leadership . . . Fortunately, we were a place that had a lot of world-renowned scientists and a great tech company. We moved immediately, creating our own playbook, trying to get people to work from home and that showed that we were able to flatten that virus really quickly by having such a quick response from our employers and the city. But then we needed to employ a whole other series of measures, because suddenly we had no playbook for all the ramifications — the health and the economic ramifications. So we had to change city government to be able to provide first, frontline economic assistance to workers and to small businesses. I entered one of the first orders to stop evictions of residents and small businesses and non-profits in Seattle so we wouldn't have more people on the street. We changed our programming to deliver hot meals to seniors and grocery vouchers to families.

But we also saw that it became a “Hunger Games” between cities and states, fighting for the limited resources to fight this virus because there was no national leadership.

Mayors are working together across this country to learn best lessons from each other, to see what's working, to help each other, and to write the playbook as we go. We are in this together, not just in America . . . And that has I think built a sense of unity that we know that to get through this, we've got to be smart.

Gillian Tett (GT): Mayor Suarez, what should have been done to avoid that [competition]? And what does that suggest about how states should interact with federal government?

Francis Suarez, mayor of Miami (FS): One of the areas where there was an enormous Hunger Games-like attitude was when it came to the Cares [Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security]Act funding. If you were not a city with a population, according to the census, of over 500,00, you did not get a direct payment from the federal government. For example, a city like Atlanta . . . had a population adjusted of 506,000, they got $88m from the Cares Act which was critical to helping do a lot of the things that Mayor Durkan was talking about . . . The city of Miami [population 470,000] got $0 from the Cares Act, and we're a city that had a $20m surplus going into Covid, we ended the year with a $25m deficit . . . So, we were actually looking at the possibility of having to let go police officers and firefighters, those who were on the front lines and who were taking the most risk in this Covid fight to protect our citizens and our residents. And so, I think that was a major mistake in the rush to get all that money out. There was not a thought to allow . . . all the cities that were below, which are the vast majority of them — of 500,000 in population, there's only 30 plus cities in America that met that threshold.

GT: What is the responsibility of national government in respect to vaccinations?

Bill Peduto, mayor of Pittsburgh (BP): The co-ordination of the distribution is the primary responsibility of the federal government . . . You simply can't put these vaccinations on a truck and ship [to where they are needed]. They need to be in a cold atmosphere, which means we need refrigerated transportation in order to be able to ship. We don't have enough trucks in this country to be able to distribute right now and that's just one little part of the logistical steps that will be needed in order to co-ordinate a mass national programme, let alone a global programme.

GT: Would you have taken on this job a year ago if you'd known what it was going to be turning into? Maybe I can start with you Mayor Peduto, because I think you've got the biggest grin.

BP: We're getting it from the right and the left, whatever [the decision being made], people are so polarised right now, but they are also very set in their ideas. What we have to do is do the job of being pragmatic in getting the job done . . . Somebody once said to me, and I believe this: there's three parties . . . Democrats, Republicans, and mayors. We don't get the opportunity to be philosophical, or to try and just spread a theory. We have to pick up the garbage on Monday morning. And so, in this crisis, of both a global pandemic and a national emergency centred on racism, we are dealing with all of the side effects of both . . . what makes the job difficult is when those issues become politicised . . .[But yes] I would have said I want to be a mayor and that’s what you sign up for.

How to battle the mafia — then Covid-19

Palermo’s long-serving mayor Leoluca Orlando (LO), pictured above, explained in conversation with Leyla Boulton, special reports editor (LB), how the experience of fighting the mafia equipped him and his city to battle Covid-19 with the help of what he called “alternative populism”.

LO: There is nothing so global like the virus . . . The other global activity in the world is digital. So, the mayor has to be near to the people, to touch the people, and to use the digital system to let the people be a community . . . the first time I was elected mayor was in 1985 . . . and in 2020, I feel like [a] start-up mayor because the virus has changed our perception of time, our perception of space, our relations with economic activities, our contributions to economic development. We have to take care of human rights just using digital, not letting the citizens be abused by digital [misinformation on social media etc].

LB: How do you actually win the argument? Populism has been a very powerful force in Italian politics over the past few years. So, what does it take to actually get people on your side?

LO: A populist has no respect for time, a populist imagines that it is possible to change everything, to solve a problem . . . without problems. I am not a populist . . . Real change needs time — I have respect for time.

In my [mayoral] chair forty years ago [was] a mafia boss. [If I had said at the time that I will free Palermo] from the government of the mafia in three months, I would be populist. We needed 40 years to say clearly that the mafia does not govern the city of Palermo.

In the fight against the virus, we need to send a message of [the need to respect] time. The people have to understand that it is not possible to solve the virus today or by Monday. We need time. This means that we need to respect the rules, to take care of our health and the health of our relatives and of other citizens . . . the mayor is something like an educational agency.

Comments