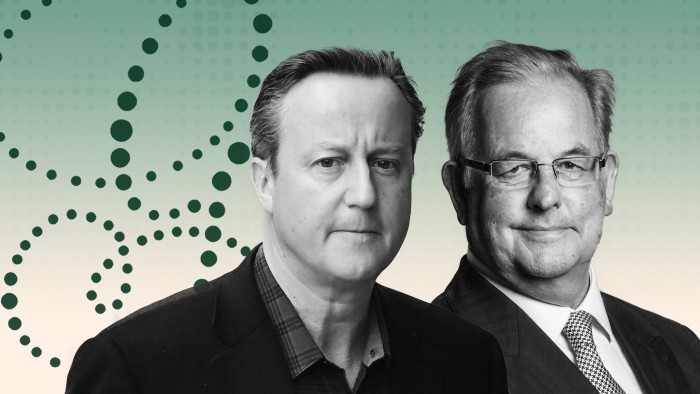

David Cameron lobbied Tory associate at Lloyds Bank to rescue Greensill deal

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

David Cameron lobbied Lloyds Banking Group to reverse a decision to cut ties with the ailing Greensill Capital, appealing to a board member whom he had ennobled while prime minister.

Cameron lobbied Lloyds in January, according to people familiar with the matter, when he contacted Lord James Lupton, a director of the bank who had previously been a Conservative party treasurer, in a successful attempt to persuade the bank to continue doing business with Greensill.

Lupton, Tory treasurer from 2013 to 2016, has donated more than £3m to the Conservative party and was appointed to the House of Lords in 2015, sparking accusations of cronyism against then-prime minister Cameron from rival politicians.

Cameron earned millions of pounds as a boardroom adviser to Greensill, the supply-chain finance company whose unravelling earlier this year dragged the former prime minister into Westminster’s biggest lobbying scandal for a generation.

Months before Greensill’s collapse in March, Lloyds indicated that it would stop doing business with the group, jeopardising a supply-chain finance scheme for NHS pharmacies operated by Greensill that relied heavily on the UK bank for funding.

After Cameron’s plea — which flagged the threat Lloyds’ withdrawal posed to the NHS scheme — the bank reconsidered its decision and agreed to continue funding the pharmacies for a period, said the people familiar with the matter.

Lupton had declared his relationship with Cameron when passing on the former prime minister’s request. However, some people inside the bank found the former prime minister’s intervention via Lupton to be surprising and unwelcome, coming after the lender had made a business decision to end the relationship. They said it was decisive in causing the U-turn.

Lloyds said: “The decision to continue this facility in January 2021 was made on the usual commercial basis and in recognition of the importance of maintaining this facility for the NHS during the height of the pandemic.”

“This programme ended following the administration of Greensill, with the bank repaid in full,” Lloyds added. “There were no losses to the NHS, the pharmacies supplying them or Lloyds Banking Group.”

Greensill declined to comment. Cameron did not respond to requests for comment. Lupton did not respond to direct requests for comment and declined to comment via Lloyds.

Cameron was aware of the parlous state of Greensill’s finances when he approached Lupton, having later told MPs investigating the group’s collapse that he first “became concerned that the company might be in serious financial difficulty” in December 2020.

The company’s founder, Lex Greensill, helped establish the “Pharmacy Early Payments Scheme” — which paid chemists for dispensing prescriptions ahead of the NHS settling the invoice — during his stint as a government adviser to Cameron. The scheme was later administered by his eponymous finance company.

The former prime minister has touted the benefits of the scheme when defending his work for Greensill, stating in April that it “successfully reduced costs to the NHS and enabled many thousands of pharmacies to access early payments and low-cost credit”.

But while Greensill and Cameron have both claimed the scheme saved the government £100m a year, the UK’s public spending watchdog said last month there was no evidence the programme provided any benefit to taxpayers.

Cameron has also previously cited the NHS scheme when defending Greensill’s controversial “future receivables” product, in which the company financed hypothetical invoices that did not yet exist.

“An algorithm was being used to help predict the prescription behaviour of each chemist, so they could get the money in advance of actually making the prescriptions,” he told MPs in May. “This was incredibly popular with pharmacies.”

However, the National Audit Office’s report found this practice made the pharmacy programme riskier for the lender and that “no other finance provider was willing to take on the risks that Greensill Capital had assumed”. This meant the government had to step in and provide funding to pharmacies when Greensill collapsed.

Greensill acted as a middleman when arranging funding for the programme, with banks such as Lloyds providing the financing.

Lloyds had decided to back out of the arrangement in January after Morgan Stanley stopped distributing Greensill’s invoice-backed investment products. The imprimatur of the US investment bank had previously given the UK lender comfort, people familiar with the discussions said.

Greensill had tried to reassure Lloyds that Morgan Stanley was due to be replaced by Credit Suisse but, before Cameron’s intervention, the UK bank had refused to resume any funding until the Swiss bank started the role, according to the people with knowledge of the discussions.

Credit Suisse had existing deep ties with Greensill, which have since exposed some of its richest clients to potentially billions of dollars in losses, after the Swiss bank channelled $10bn of their money into opaque investment products that funded some of Greensill’s highest-risk clients.

Comments