How China’s football investors are staying positive amid government crackdown

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Property billionaire Wang Jianlin’s acquisition in 2015 of a 20 per cent stake in Atlético Madrid, one of Spain’s most storied football teams, marked the start of a $2.5bn spending spree on European clubs by a plethora of Chinese tycoons.

Wang’s Dalian Wanda group had long invested in domestic football. But other businessmen, from top deal makers to little-known investors, rushed to join him abroad, taking stakes in or buying out clubs from giants including Manchester City, AC Milan and Inter Milan to lesser names such as Auxerre, Slavia Prague and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

From slick media mogul Li Ruigang, whose China Media Capital invested in Manchester City, to forthright Twitter pundit Tony Xia, who bought Aston Villa, their motives were diverse.

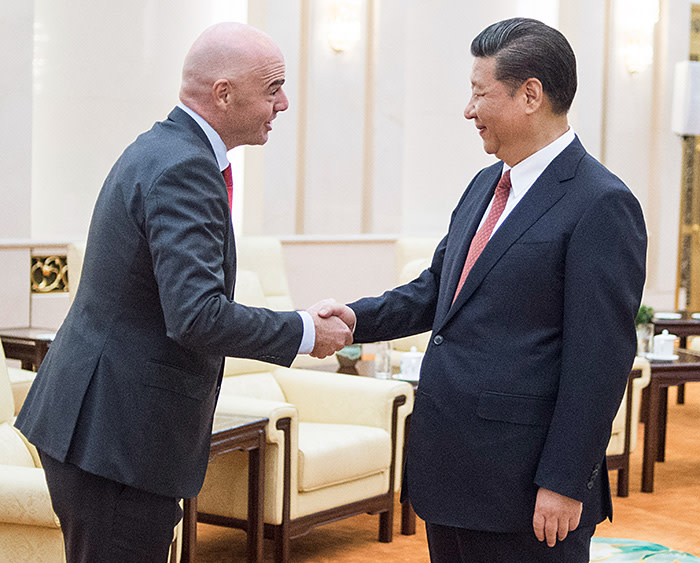

In addition to the usual desire for a frisson of excitement and an outside bet on financial success, many wanted to win brownie points from Chinese President Xi Jinping.

A football supporter with a jersey collection that would “make even the top fans green with envy”, according to a cloying profile by state news agency Xinhua, Xi called for a sporting revolution in China that would see the world’s most populous nation finally throw off its status as a football minnow.

But just a little more than two years after helping spark the headlong rush into football, the government slammed on the brakes, as part of a wider series of capital controls designed to curb “irrational” outbound deals that were often fuelled by debt.

In February, retuning his political antennae, Wang became the first Chinese investor to divest his stake in a European football club, selling it for €50m, at a slight profit of €5m.

Beyond the weird and wonderful world of football investment, the rapid turnround reveals much about the risks facing tycoons in China as they aim to curry favour with the Communist leadership while carving out business opportunities and enjoying the high life.

Whether it is property development, robotics or football, China’s investment booms often follow a pattern.

First, the state signals a desire to achieve greatness in a particular sector. Next, investors pile in, supported by state-owned and private banks keen to do their bit. But then officials start to worry about the quality of the investments as well as the build-up of debt, so they call for a sudden halt.

“What’s happened in football is typical China,” says Mark Dreyer, who runs a website called China Sports Insider in Beijing. “There’s a green light and everyone is ‘go, go, go’. Then there’s a red light. And now we’re kind of on a yellow light.”

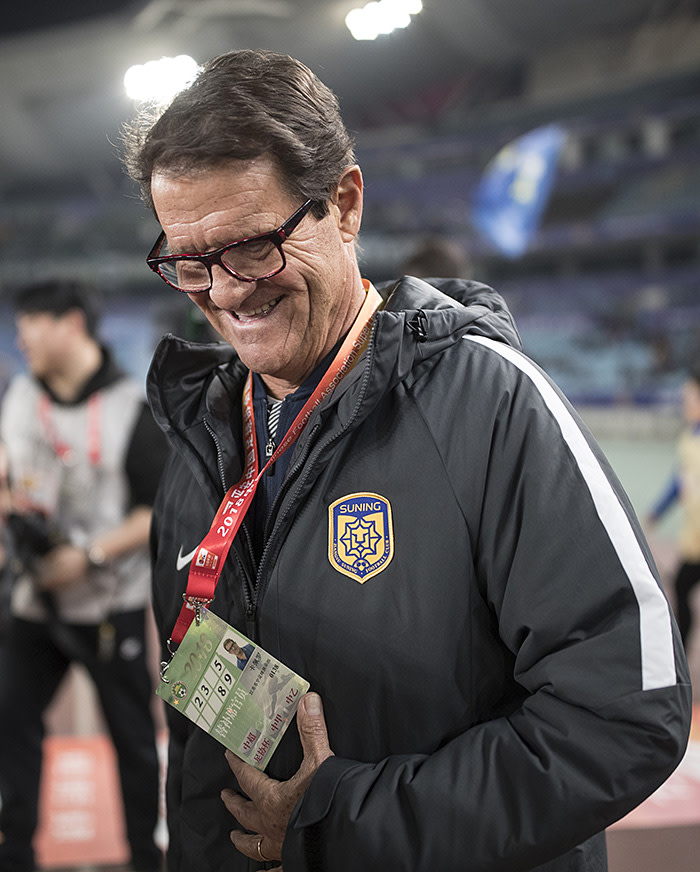

The policy shift has also affected the fast-improving Chinese Super League (CSL), the country’s premier football competition. A big boost in spending on foreign players by the property and consumer industry tycoons who own the CSL’s 16 clubs helped grow attendance, with more fans now watching the average game in the stadium than in the top leagues in France, Italy and the Netherlands, according to figures collated by Transfermarkt, a football data website.

But the government called a halt to this equally “irrational” spending last year, restricting the import of foreign players and implementing a 100 per cent tax on transfer fees of more than Rmb45m ($7m).

On top of the worries about capital flight, Xi had also grown wary of his name being used to justify questionable deals, according to two senior Chinese football executives.

But while the days of throwing silly money at foreign clubs and players are over for now, the government remains committed to its long-term plan to develop football in order to eventually achieve Xi’s three dreams for China: to qualify for the World Cup, host the event and, one day, win it. In practice, this means tycoons are likely to shift their investment to developing Chinese players and improving youth coaching and training facilities.

Fifa, world football’s governing body, officially requires all national football associations to be free of political interference. But in Xi’s China, where the Communist party continues to grow in influence, nothing is free of such interference.

At a pep rally ahead of the new CSL season, which started in March, the Communist party secretary for the Chinese Football Association told club owners to study and implement “Xi Jinping Thought” and to remember that developing football was vital for the Chinese leader’s dream of “national rejuvenation and national prosperity”.

When it comes to investors’ own prosperity, all the CSL teams are loss-making and many of the overseas football ventures are likely to prove so too.

Chinese football investors admit that they are unlikely to make profits at club level any time soon, with television rights and match-day revenue far below European levels. But, in the longer term, they hope to generate subsidiary revenues by using their links to football, and its huge fan base, to promote their other businesses, from property development to ecommerce.

As is true in so many areas of Chinese life now, the future will be determined by politics. “We’ve seen a lot of attention by the top levels of the leadership in government on football,” says Nikki Wang, head of sports business development for Deloitte, which advises the CSL and several Chinese football investors. “That’s why we always feel quite positive about the development of Chinese football.”

Comments