The ice pack: how hip-hop jewellery became big business

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

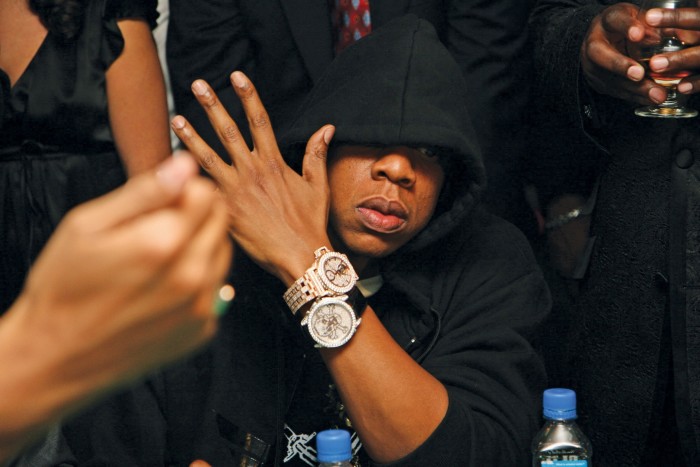

Everyone knows that larger-than-life jewellery is an essential ingredient of hip-hop style, as a cultural identifier, personal style signifier and, perhaps most importantly, symbol of success. The chains, medallions and rings worn by the stars of hip-hop have typically come from a handful of niche, exclusive names. Jacob the Jeweler, whose clients include Diddy and Jay-Z, is perhaps one of the best known, famed for his diamond-smothered, five-time-zone watches – including a Supreme collaboration model. There’s Avianne, also in New York, and Los Angeles’ Ben Baller – a favourite of Kid Cudi and Tyler, The Creator and the maker of Drake’s blue, yellow, pink and white diamond OVO necklace. Lorraine Schwartz also makes big-ticket items, including the 2B Happy diamond bracelets worn by Pharrell.

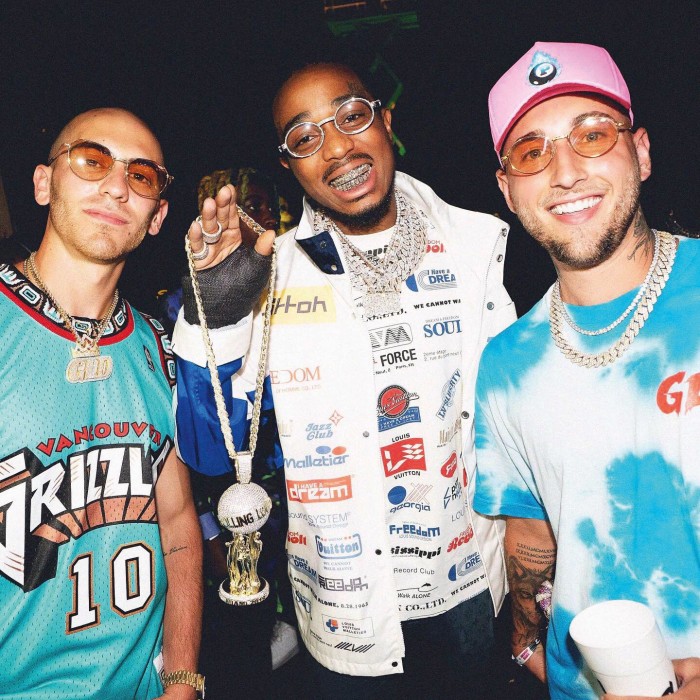

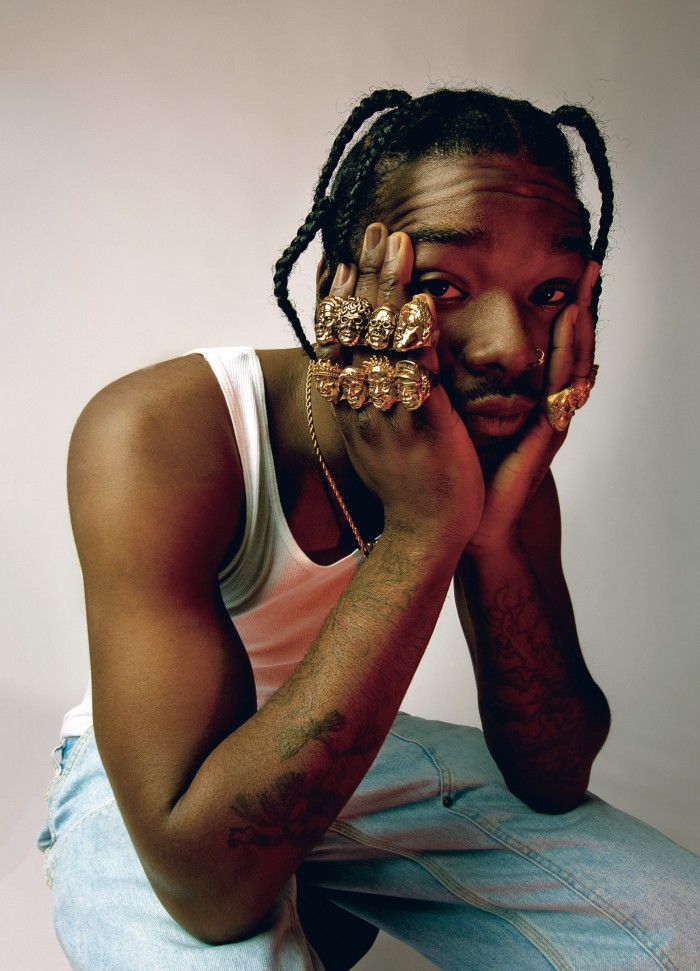

But lately, the motifs of hip-hop have been seeping into the broader jewellery and fashion market, too, thanks to the work of Virgil Abloh at Louis Vuitton or Matthew Williams at Givenchy, as well as via a handful of contemporary brands. London-based O Thongthai, which makes pendants and studded signet rings favoured by ASAP Rocky, was picked up by Browns Fashion last year. There’s also Johnny Nelson, a New York-based jeweller who creates necklaces and rings depicting famous figureheads, including a four-finger ring known as the Hip Hop Mount Rushmore – featuring the faces of Biggie, Tupac, Ol’ Dirty Bastard and Eazy-E. Nelson made another one-off four-finger ring, this time depicting famous female musicians, for a recent Sotheby’s auction. The brand making the biggest impact in this realm, however, is GLD – a Miami-based jewellery business founded in 2015 by Dan Folger and Christian Johnston. The duo hope GLD will become the first jewellery “brand” to popularise the space in the same way that Nike, say, has done with footwear. CEO Mark Seremet says GLD offers accessible luxury with “cultural relevance”. The accessibility is owed to a price structure in which identical jewels and watches are available in different materials and at different price points: a gold-plated necklace “iced” with cubic zirconias costs $329, for example, while the same style in 10ct solid gold and diamonds costs $59,500. It’s a strategy that would be anathema to a mainstream jewellery brand.

Folger and Johnston are childhood friends who grew up in the suburbs of Pittsburgh and were both infatuated with skate culture, streetwear and hip-hop. As teenagers, they vowed to start their own lifestyle brand. When, in their early 20s, they wanted to buy jewellery, they couldn’t find what they wanted. “It was all either too cheap and badly made or very expensive,” says Johnston. “We wanted to be proud of our jewellery, to truly belong to hip-hop culture.” They saved $1,500 between them, took the bus to New York and spent it all on a shoebox-full of jewellery they picked up in the city’s Diamond District, on 47th Street, with a view to reselling it back home. They worked out of Johnston’s dorm room and the basement in Folger’s parents’ house.

Using Instagram to showcase pictures of themselves wearing the jewellery, and persuading Johnston’s teammates on the Duquesne basketball team to buy it, the pieces sold well. Before long they were designing their own styles, and moving into a small office in Pittsburgh through which to grow their sales. A year later, they were introduced to Seremet, a serial tech entrepreneur who, among other ventures, co-founded the company responsible for Grand Theft Auto. “It was clear to me that this company had a trajectory to be wildly successful,” says Seremet. In 2017 the company moved to a space in Miami; it’s now based in a 12,000sq ft facility in the city’s arts and culture district and employs over 60 people. Its first store is due to open there this year.

GLD’s annual revenue has increased from $300,000 in 2015 to more than $50m in 2020. The brand has secured noteworthy licensing deals, including with the NBA and Marvel, and has become embedded in the hip-hop community, referenced in songs and attracting a celebrity clientele. Wiz Khalifa, who also comes from Pittsburgh, is one such customer. “As soon as you become a rapper yourself, you want to start your own jewellery collection,” Khalifa says. “That’s how jewellery continues to be part of rap culture.” He buys from GLD two or three times a year. “I look for personality, unique look, style and cut. And it’s got to be clean. If you’ve got a nice chain and a nice piece – your name or the name of your record label – that’s a significant piece. Now more than ever in hip-hop, a nice watch will put you far ahead in the game.”

Seremet says the key to their success, and what sets them apart, is the quality of their entry-level jewellery. This has always been a prime focus – an $899 watch “shines like crazy”, looks the same as the $39,999 version, and is made with as much respect, care and attention. He likens their business model to Mercedes: “There are entry-level cars – C-Class – and you can work your way up to the high-end models – S-Class. All are great cars and all allow people to participate in the brand.”

At the same time, the influence of hip-hop continues: double-digit rings, hand-bracelets, ear-stacking, gold chains, name necklaces and medallions feature at many of the major houses. Traditional jewellers are also making personalised, one-off pieces – an important element of hip-hop style. Brazilian artisan-jeweller Ara Vartanian has made bespoke brooches for Swizz Beatz.

And Paris-based jewellery house Messika is a favourite of Beyoncé. The singer has commissioned bespoke hoop earrings and a custom-made choker, called the Equalizer, which she wore to the 2020 Super Bowl. She was also wearing Messika high jewellery in her 2018 video for Apeshit, alongside Jay-Z, who was adorned with a giant gold medallion necklace.

“Rappers are collectors; they buy rather than borrow jewellery,” says Sarah O’Brien, international business development director for jewellery at Phillips auction house. “The mantle has been passed from the great 20th-century collectors, Hollywood stars like Elizabeth Taylor, to the stars of hip-hop.”

Maybe a touch of hip-hop is just what the Place Vendôme jewellery world needs. Jewellery that is simply, transparently joyful – a sign of pride, success and wealth, rooted in the culture of our times. For GLD it’s about belonging, being part of “something bigger”. As Johnston says: “My goal is to impact my culture as much as that culture has influenced us.”

Medallions of honour: the classic necklace gets a 2021 makeover

By Jessica Beresford

Comments