The spectre of high inflation returns to haunt Latin America

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

While policymakers at the US Federal Reserve conduct a drawn-out discussion over the pros and cons of starting to withdraw their multitrillion dollar pandemic stimulus, south of the border the debate is already over.

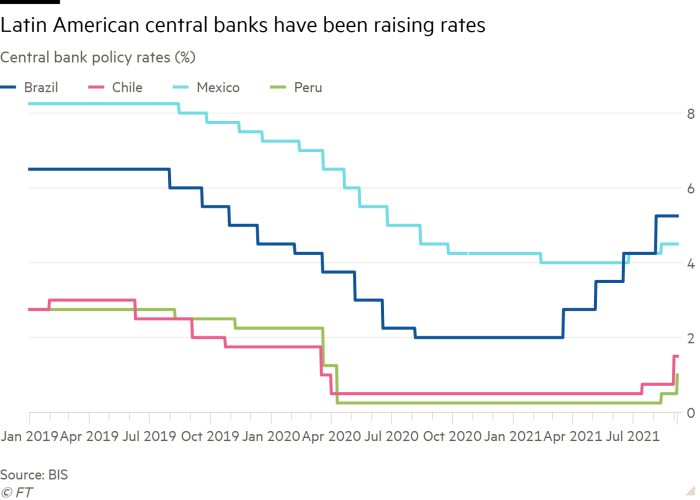

Inflation is back with a vengeance and Latin American central banks are raising rates, some aggressively.

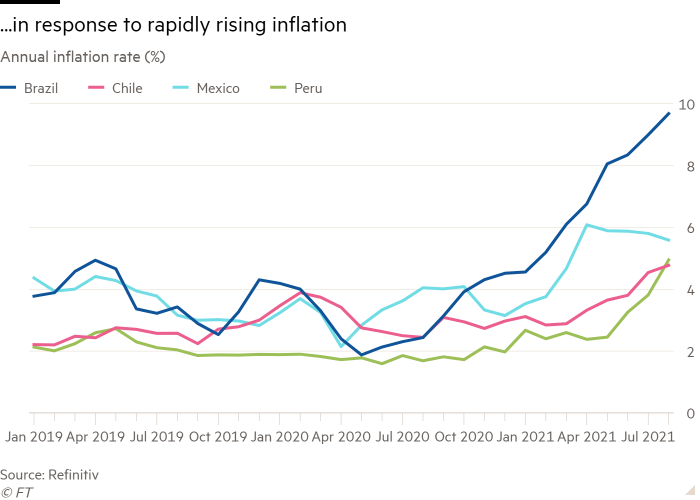

Leading the pack is Brazil, where the newly independent central bank is struggling to prevent inflation from hitting double digits. “Brazil really had a very big inflation shock,” central bank governor Roberto Campos Neto admitted on September 1. Days later figures were published showing annual headline inflation at a five-year high of 9.7 per cent in August.

Brazil has already raised its reference interest rate four times since March to 5.25 per cent and investors expect another increase of at least 1 percentage point this month, with more to follow.

Inflation causes particular alarm in Latin America because of the region’s long history of price instability, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s. Newly empowered central banks brought prices under control in most of the major economies over the past two decades but the region has never completely exorcised its inflationary demons.

Venezuela had the world’s worst inflation of 5,500 per cent in 2020 and prices in Argentina are rising more than 50 per cent a year as the central bank prints money merrily to fund a deficit — another bad old Latin American habit.

In Mexico, core prices rose last month at their highest rate since 1999 and Citibank expects inflation for 2021 of 6.1 per cent. Although the central bank never cut rates as aggressively during the pandemic as its peers, it has tightened policy twice this year and Citi expects two more rises before the year end, taking the policy rate to 5 per cent.

The same story is repeated along the Andes. Annual inflation in Chile hit 4.8 per cent in August, almost double February’s level. The central bank published a hawkish inflation report, signalling further tightening after doubling rates last month. In neighbouring Peru, inflation reached 4.95 per cent in August and the central bank has started tightening while in Colombia prices rose 4.4 per cent a year in August.

“The picture is getting uglier by the day with the inflationary pressures rapidly disseminating ”, said Alberto Ramos, head of Latin America economics at Goldman Sachs. “It will likely take a significant amount of policy tightening to put the inflation genie back in the lamp.”

Latin America was hit harder by the combined health and economic impact of coronavirus than any other region. Rapidly rising interest rates now threaten to choke off a recovery which was already losing steam as government stimulus programmes wound down and prices for commodity exports levelled off. JPMorgan expects that growth of 6.4 per cent in the region this year will slow to just 2.4 per cent next year.

“Central banks in the region don’t have a choice,” said Ernesto Revilla, head of Latin America economics at Citibank. “They have to tighten monetary policy despite a weak economy because they can’t allow inflation expectations to drift off. It’s the curse of emerging market central banks”.

Latin American policymakers are casting envious glances at the US, where the Fed has so far been able to continue its multi-trillion-dollar economic stimulus despite inflation hitting a 13-year high in July.

“The Fed can keep saying that inflation is transitory and there is no need to overreact,” said Claudio Irigoyen, head of Latin America economics at Bank of America. “Eventually it will pay a price but the reality is that the world pays in dollars . . . Latin American central banks don’t have the luxury of saying ‘this is a temporary change in inflation’”.

The rising threat of inflation comes ahead of an election cycle that will see new presidents elected in Chile, Colombia and Brazil over the next 13 months, while Peru and Ecuador chose new leaders earlier this year. Voters are venting their anger over pandemic missteps on incumbents and favouring radical outsiders, a dynamic which bodes ill for central banks.

Banco de Mexico’s rate rises have already triggered a political row with populist president Andrés Manuel López Obrador. “Although Banco de Mexico should be paying attention to inflation and growth . . . for a long time they have only been concerned with inflation,” he said at his morning news conference last month.

Irigoyen said he saw “a decent chance” of more radicalisation in the upcoming election. “This will create a lot of pressure on currencies and a demand for high spending, which will put pressure on central banks,” he added. “In the US there are more and more people claiming that the Fed should accommodate fiscal deficits. People in Latin America will say ‘if they can do it, why can’t we?’”

michael.stott@ft.com

Comments