Memorial Drive, by Natasha Trethewey — defiance, remembrance and race

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The first chapter of Memorial Drive — “Another Country” — shares its title with James Baldwin’s 1962 novel of memory and of blackness. Natasha Trethewey, an African-American woman and former US poet laureate, begins her new book as she means to carry on: “There is a large birthmark on the back of my thigh. Even though it has been with me over half a century, I can’t recall which leg bears its dark outline, and so I have to look at myself backward in a mirror to remember.”

This is the first sign that Trethewey’s meditation on the murder of her social worker mother, who was killed in 1985 by her second husband, does not have a straightforward narrative. It refuses to “go gentle into that good night”. It is the work of a poet. A great poet.

Reading on, there are moments when you pull yourself away from this work simply to admire its sheer artistry. A photograph of Trethewey’s mother is described like so: “My mother . . . just begun to wear her hair in an Afro . . . There’s a flaw in the picture, a white spot in the center of her face from which she already seems to be disappearing.”

Memorial Drive is part investigative report; part confessional; part black, feminist and black-feminist history. It is also a look at battered women and their tragedy. But above all, this book bears witness to the Via Dolorosa of Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough.

It was a journey that had already begun the day that Trethewey was born: “On her way to the segregated ward [my mother] could not help but take in the tenor of the day, witnessing the barrage of rebel flags lining the streets: private citizens, lawmakers, Klansmen (often one and the same) raising them in Gulfport and small towns all across Mississippi. The twenty-sixth of April that year marked the 100th anniversary of Mississippi’s celebration of Confederate Memorial Day — a holiday glorifying the old South, the Lost Cause, and white supremacy — and much of the fervor was a display, too, in opposition to recent advancements in the civil rights movement.”

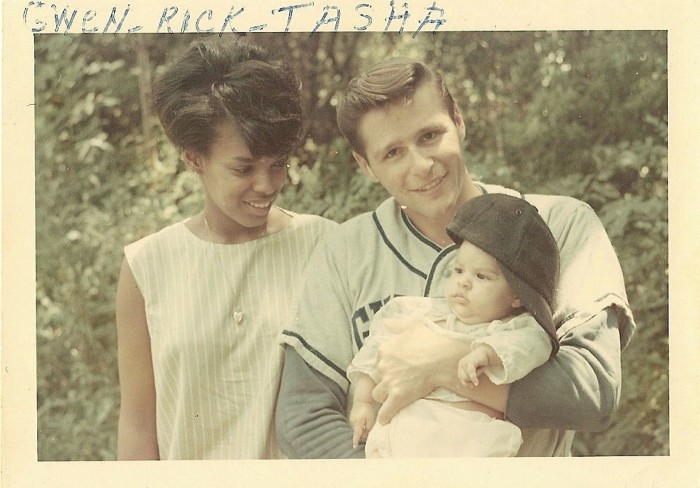

Trethewey, the child of an African-American mother and a white Canadian father, describes the Mississippi where my own late father was born: the cruelest state if you happened to be black. She was born in 1966, the year before the chief justice of the Supreme Court stated that the freedom to marry resided with the individual and no state could impinge on that freedom. Her parents had travelled to Ohio in order to marry. “If I was with my father, I measured the polite responses from white people, the way they addressed him as ‘Sir’ or ‘Mister’. Whereas my mother would be called ‘Gal’, never ‘Miss’ or ‘Ma’am’.”

Her parents divorced and her mother later remarried, this time to a black man who would become her abuser and eventually her murderer. It took Trethewey decades to summon the courage to read about the circumstances of the death of her mother. In between times, Trethewey lived in and outside of her poetry; she kept her head down; and she attempted to survive and thrive as a black girl and an artist.

It is too easy to say “Black Lives Matter”. Memorial Drive, the last address of her mother, and the location of her murder, takes us past that slogan to an analysis of oppression. And it is a testament of what I call “Meta Africa”, that terrain of the human spirit forged in the person of the enslaved African, trapped in bondage and segregation. The aim of slavery was the erasure of our origins, of our true names and language, of our memories. Trethewey’s masterpiece suggests that the greatest act of defiance a black person can do is to remember.

Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir, by Natasha Trethewey, Bloomsbury, RRP£16.99, 214 pages

Bonnie Greer is a playwright, novelist and author

Watch Natasha Trethewey and Lilah Raptopoulos discuss writing about memory and history FT Weekend Digital Festival

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café

FT Weekend Digital Festival

Join the FT for 3 days of digital debate and entertainment, and your ultimate guide to our changed new world

Comments