Not Vital brings his transcendental structures to Hauser & Wirth

Simply sign up to the Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

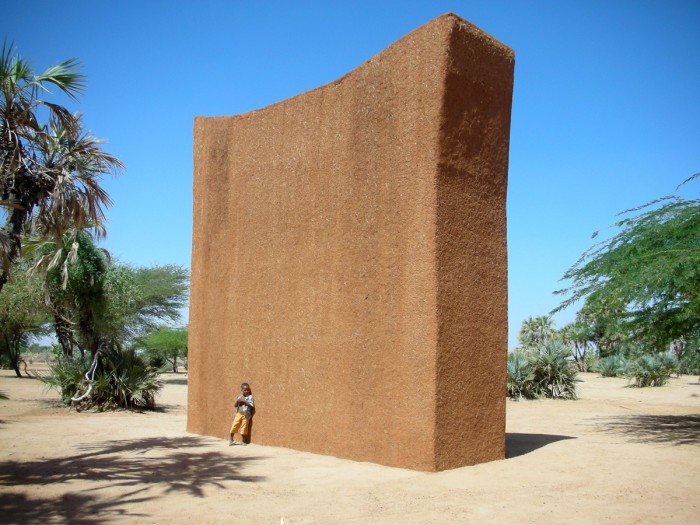

There are many reasons to celebrate the opening of a major exhibition of Not Vital’s work at Hauser & Wirth Somerset this month, but perhaps the most crucial is that Somerset is a relatively easy place to get to. Since the early 2000s, the nomadic, Swiss-born 71-year-old has created several architectural site-specific structures – works he has dubbed “scarch” (a fusion of “sculpture” and “architecture”) – in some of the world’s most remote places. They range from NotOna, an excavated cave on an island of marble in Patagonia, to towers – one from which to watch sunsets, another the night skies – in an oasis in the Saharan desert in Niger.

Although Vital is extremely prolific – his output comprises thousands of works on paper, sculptures and paintings – experiencing his most dramatic scarch projects requires daunting journeys. To see his House to Watch Three Volcanoes in the remote Indonesian village of Moni, for instance, requires a flight to Bali, then another domestic flight to the island of Flores through the port city of Labuan Bajo, continuing on to the lesser-known city of Ende. From there it’s a two-hour drive on one lonely dirt road through jungle and lush green hills to Moni itself – essentially a few dozen earth buildings, bamboo huts and backpacker cafés scattered on a terraced slope at the foothills of Kelimutu, a sacred volcanic mountain.

I made this pilgrimage last autumn. If you didn’t know to look for it, you might not even know Vital’s tower is there, hidden entirely as it is from the main road. But if you ask the locals about it, you’ll become the subject of their keen attention and curiosity. I was told to search out a woman called Rose, the work’s official keeper. By the time I arrived at our designated meeting point, everyone in the village seemed to know that I was headed to Vital’s tower.

Vital later told me that he almost always realises his projects “in close collaboration with the respective communities and with local materials. Then, once the structures are erected, the communities live with them and often take care of them. I always find a person I can trust to do so.”

From a distance, the Moni tower – which was technically completed in 2017 but which the artist is still tinkering away at here and there – appeared to be a sort of a modernist white Aztec pyramid with a zigzag of metal stairs climbing almost to its pinnacle. (Most of Vital’s structures are exactly 13m high.) There is no railing, so the ascent requires a bit of fortitude (“I’m not brave enough,” Rose’s husband laughed when I asked if he had been to the top). My heart pounded the entire way, fear as much as awe slowing time to an excruciating crawl. At the top, though, exhilaration poured through me; viewing the surrounding emerald-green terraces and the slopes of Kelimutu, I felt like I had passed a test.

Back on the ground there is more to discover: a small entrance at the right angle of the structure leads into a dark space lined with bamboo and thatch, like a traditional bungalow turned inside out. The materials are so unexpected – and the pungent scent of thatch in particular so overwhelming – that my senses baulked as they adjusted. I felt I’d entered a cave, primitive and disturbing, but over the course of several minutes my perception changed – it became a beautifully textured, calming space, like a chapel woven of reeds. When I exited, blinking furiously in the tropical Indonesian sun, I could appreciate more fully the area’s near-spiritual significance. My second thought was that I wanted to see more of Vital’s habitats, as soon as possible.

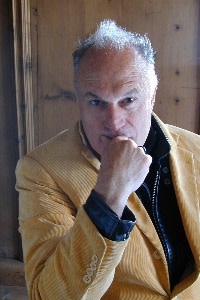

As luck would have it, I recently met Vital himself, several months after my pilgrimage to Flores, in a setting as dramatic as the one described above – Schloss Tarasp, an 11th-century castle once owned by the aristocratic von Hessen family and located on a dramatic precipice that juts out in the middle of the Lower Engadin valley. Vital recalls it as a landmark of his childhood, and owns it. Born and raised in Sent, a village not far from St Moritz, Vital is Engadin to his core, despite his nomadic wanderings. His name is a traditional one in Romansh, a language still spoken by about 60,000 people in the region, and his mother tongue; in one of his houses, a historic five-storey building in the nearby village of Ardez, Vital keeps one of the world’s largest libraries of books and manuscripts written in the language. At the age of 17, he translated the Saint-Exupéry classic The Little Prince from French to Romansh.

Over the past two decades, Vital has purchased and built several “homes” and projects in and around Sent, including a sculpture park where his first official scarch works were born – a house that disappears into the ground with the touch of a button, and an “invisible” bridge that leads to nowhere. Since buying the castle in 2015, he has worked to transform it and its grounds into a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, treating it as archive and art space, installing his own work and that of artists he admires both inside and across the surrounding estate. Vital chooses to sleep in a tiny bedroom on the first level, decorated with several Rembrandt etchings, a Jean-Michel Basquiat drawing that reads “Astro-Not” made for him by the artist himself, and a modernist chair designed by the father of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius.

Vital describes how as a child his greatest joy was in building cocoons of branches and secret snow forts in the forest, in which he would hide for hours. To some degree his scarch projects derive from a similar desire; but, he says, each habitat is “born out of a different necessity. While most of them fulfil a transcendental purpose, such as watching the sunset or night skies, others – like the school I built in Niger – fulfil a social purpose.”

In Somerset, Hauser & Wirth will install several examples of Vital’s scarch works both inside the gallery and outside in the landscape, among them a model of one of his House to Watch the Sunset structures (his plan is to have one on every continent; so far they exist in Brazil, Switzerland and Niger). The next iteration of this structure, built of aluminium, will eventually travel to Venice in May for the Architecture Biennale, after which it will make its way to its permanent home on the tiny island of Fangasito, in Tonga. Coinciding with the Hauser & Wirth exhibition is the publication of a large monograph dedicated to Vital’s scarch projects, edited by his long-standing collaborators Giorgia von Albertini and Olivier Renaud-Clément – a book that has been years in the making.

Somerset, with its singular landscapes and connection to nearby pilgrimage sites such as Bruton’s Dovecote, King Alfred’s Tower and Glastonbury Tor, is an ideal site for Vital’s work, says Iwan Wirth. “Not’s nomadic approach to making and viewing art has great synergies with the ethos [of what we do]. He not only explores how his structures can exist within remote locations; he also engages communities in their development from the outset.”

The gallerist Alma Zevi, who is working on another important book of Vital’s work, adds: “Much of it is about giving back to the community in which he creates, whether that’s in the Engadin or in [Africa].” Vital’s vision, she says, owes much to the fact that he never really engaged with the international art scene. “He was never part of any artistic group, whether here in Switzerland or the New York painters of the ’80s. He knew Warhol and Basquiat, but he has always followed a very autonomous path.” Vital is currently creating a piece for her gallery in Venice in May, to coincide with the Biennale – an experimental work made entirely of glass, currently being produced in Murano. “Walking on it should be like crossing a frozen lake,” says Vital.

Unexpected, disorienting, abruptly sense-heightening: Vital’s spaces generate a sense of transcendence on a par with what nature itself can do. He’s an artist who creates just enough tension between his installations and their environments to cast both in a revelatory new light.

Scarch opens on January 25 2020 at Hauser & Wirth Somerset (hauserwirth.com).

Comments