Axel Vervoordt: ‘The only way to be creative is to be open-minded’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I’ve just fallen off my horse.” Axel Vervoordt appears over video link, clearly intact as he strides into his office with an energy that is obscene for a septuagenarian. He collapses in his chair, laughing. As on most days, the Belgian designer, art dealer and curator has been putting his stallion through his paces in the grounds of his 12th-century castle, which he shares with his wife, May, in ‘s-Gravenwezel, near Antwerp. Today’s gallop through 62 acres has not gone to plan. “I love horses – my father was a horse dealer – but I’m a little less passionate today,” he jokes.

Vervoordt’s ability to laugh through mishap puts me in mind of his book Stories and Reflections (Art de vivre & Voyages), in which he describes “inheriting happiness”. In it, he movingly recounts the story of his mother and her sudden decline in health due to a heart attack, which she attributed to “pure happiness”. She had attended a party at her son’s home the evening before, and been overwhelmed by the occasion. “Happiness runs in the family,” she told him, before regaling him with the story of his great-grandfather who apparently died on the spot when presented with a medal by the King of Belgium.

Vervoordt has undoubtedly inherited that gene. His spiritual approach to life and work is well documented, with former client Sting once describing him as “joyful”. He is certainly a raconteur, whose many stories include his first outing at the Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris in 1982. Ralph Lauren acquired a Gothic table. Yves Saint Laurent, Valentino and Rudolf Nureyev dropped by and became friends. Nureyev visited for dinner on several occasions. “He loved old, worn-out glamour… sumptuous food presented as in a still-life painting, and wine served in antique glasses or gilded beakers,” Vervoordt says of the Soviet ballet dancer. “That was the way May and I loved to receive guests in those days. It was the way we lived.”

Bon vivant Vervoordt may be, but he is also a serious entrepreneur and academic, building an empire over the past half-century that spans an interior design practice, an antiquaire, a private foundation, and art galleries in Antwerp and Hong Kong. Last year, the art and antiques arm of the business alone generated an annual revenue of (USD) $24.63m, and the company is still family-run from Kanaal, an old Belgium distillery transformed into a headquarters and art hub (Anish Kapoor’s At the Edge of the World is permanently installed there). “My son Boris leads the art and architecture business, which does well, and his brother Dick runs the real-estate part of the family with my daughter-in-law,” Vervoordt explains. “Their involvement has been the best present of my life.”

Vervoordt’s business acumen was evident early on. At the age of 14 he began buying and selling antiques, which he’d track down while staying with family in England during the school holidays. “There were a lot of sales in the 1960s due to inheritance tax. I brought back pieces I loved on my shoulders and in suitcases,” he recalls. He has been an Anglophile ever since.

By the age of 21, he had bought and sold his first Magritte (“That was around the time I realised I was a born art dealer,” he jokes), and started renovating a street of 15th- and 16th-century houses in the centre of Antwerp (“I made a deal and ended up buying the entire street, because I couldn’t just buy two houses. It was all or nothing”), adorning them with art and antiques, which set him on a path to restoration and interior design.

He is now 73 and his earthy, eclectic blend of purity and impeccable taste continues to be sought-after, not least within celebrity circles. Most recently, he redesigned the Calabasas family home of hip-hop mogul Kanye West, who is something of a design connoisseur himself. When interviewed by AD magazine, West compared the spare, sinuous interior to a “futuristic Belgian monastery”; he has filled it with a Vervoordt-designed table along with classic pieces by Jean Royère and Pierre Jeanneret. As is true of most of Vervoordt’s clients, the two have remained on friendly terms, with West describing his involvement in the project (with input from other notable designers) as a “coup”. They are an unlikely pairing but met, so the story goes, when the musician passed Vervoordt’s stand at the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht. West recalls being captivated by the “very soulful, emotional feeling to the space”.

It is the designer’s rich take on simplicity that provokes this emotive reaction. “I have a problem with minimalism that is too dogmatic, too black-and-white and edgy; the kind of interiors where you could almost hurt yourself if you touch them,” he says. “I like things that age well because age adds softness.”

He refers to patina as if it were a rare precious metal. “That’s why I love England and its architectural furniture, because it was made by puritans and has a patina created by generations of waxing, applied with such love. It’s impossible to imitate,” he explains. “It’s a little less fashionable at the moment, but I would still buy a great piece with great patina and I am sure I will sell it in a few years. Everything comes back.”

Vervoordt, who at last count owns some 16,000 antiques and artworks (carefully stored at Kanaal for restoration and shipment), and who is known for buying around 200 pieces for the business per month, from diverse eras and civilisations admits that he only ever purchases objects that he loves. “The very, very few times in my life that I have bought a piece that I didn’t like because it was the thing that everyone wanted, it was a mistake. I couldn’t sell it,” he says.

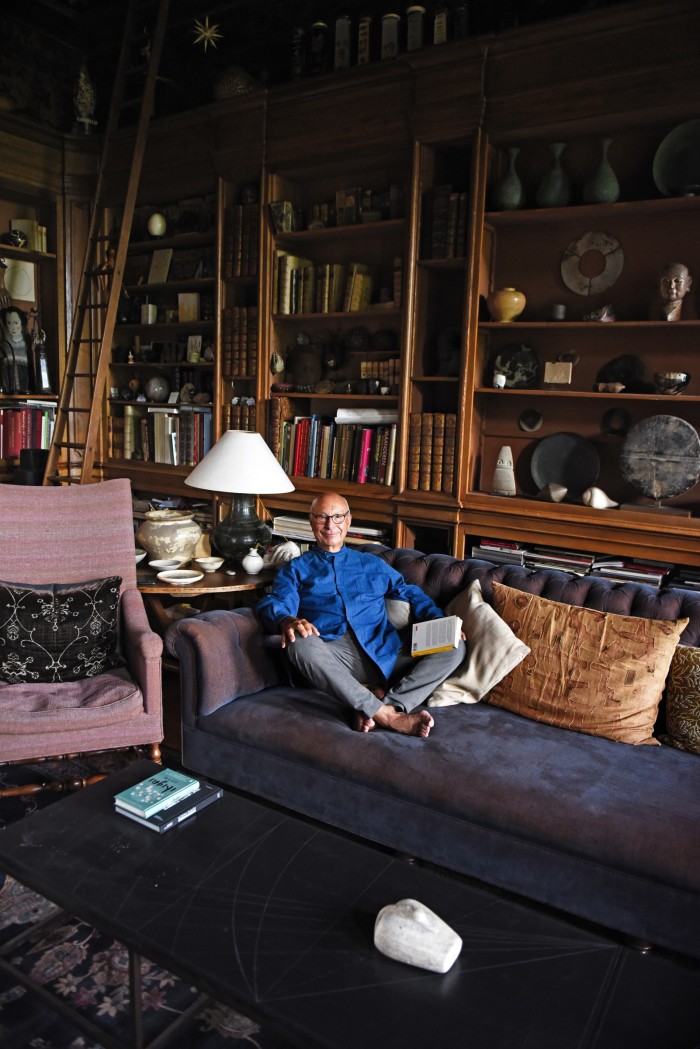

A glimpse of Vervoordt’s office – a plaster-pink, mahogany and art-filled room – brings these words home. It’s much brighter than the wabi-sabi inspired spaces he is known for. “It’s an atmosphere I like to work in,” he says, pointing out that there are 50 rooms in his castle, each decorated to suit a different mood.

“If it’s sunny I will go to sit in my Oriental room, or to the library to listen to music, but when I’m in a meditative mood, I head upstairs to my Wabi room. It’s very simple with great art all of the same spirit,” he says. “Our house is almost 1,000 years old, so every [design] period exists within it. It means that I can travel in time and travel in styles. In fact, I don’t feel the need to travel abroad anymore because I prefer to travel at home.”

His home, of course, is a reflection of his personality. “I love good food. I love good wine, but that doesn’t mean I don’t also love the monk’s life. I could live in both worlds,” he says. In the same way, juxtaposition is central to the designer’s aesthetic, and he notes with great affection the inspiration he draws from old paintings. “You see great still-lifes, where amazing Renaissance silver is mixed with a simple basket. I love the idea of using a humble piece next to important silver. This, for me, makes the silver more interesting,” he says. “It is important to have quality art, to be able to live with it and for it not to be ostentatious. It takes on a special value because you want to be charmed by it and use it.”

Vervoordt has become more attuned to the philosophical aspect of his work with time and reflection. “As I go further and get older, especially after writing my book [Wabi Inspirations, 2010] with a Japanese friend, I realise the importance of the beauty of imperfection,” he says. “It’s humble, it’s discreet, it’s close to earth but in that way it is much more spiritual. I never design a house just for show – it should belong where it is. It’s a search for harmony and also a search for the people who own it.”

The “Japanese friend” Vervoordt refers to is Brussels-based architect Tatsuro Miki who, for one residential project in Belgium, accompanied him to Japan to buy a 200-year-old minka simply to create an extension for the house. The traditional farmhouse was then painstakingly reconstructed on-site by Japanese craftsmen. Together, the pair also created a five-storey home for a family in Tokyo which has a vegetable garden on the roof. “This, for me, is the greatest luxury: to be able to live a humble country life in the middle of a busy city,” Vervoordt says.

Miki’s most talked about collaboration with the designer is the 2014 realisation of the TriBeCa penthouse for Robert De Niro’s Greenwich Hotel. The 6,800sq ft space is a masterclass in Vervoordt’s western take on wabi-sabi using local resources, and somewhat ground-breaking in its rejection of conventional notions of hotel luxury. “De Niro is such a wonderful person and when he visited the castle, he loved everything that was very humble,” Vervoordt says. “So we made the space look like a workshop, almost poor and very wabi, but with repurposed New York materials that are used in a modern way.”

He is no less meticulous in his homes for lesser-known clients, and has just completed a Manhattan apartment for a couple where 16th-century stone was sourced to create a large terrace. “It looks like an old New York pavement,” he explains. “It’s in Midtown, which is kind of industrial, so we didn’t want to make it too rich but used fantastic old materials in a very contemporary way.” Vervoordt qualifies his use of the word “contemporary” constantly. “It’s a contemporary way of thinking but not contemporary because it is fashionable. It is more connected to a love of nature than a dogmatic idea,” he says, “and my clients share this idea in many ways.”

Much of his work as a designer, he concludes, is about knowing his clients on a deep level. “I want to understand what they really want and how I can help them discover another level in their lives, which is why, for the most part, we end up becoming friends for life. I think that is because I bring something extra to their lives,” he says. The key, he adds, is that he “finds art, furniture and objects that are portals to the people who will own them”. But he also listens to his instincts: “For me, the only way to be creative is to be open-minded.” And his plans for the future? “When I look forward I don’t know what is coming next, I never have,” he says. “All I know is that I want to be useful.”

Comments