Van Gogh and Britain at Tate — the London show of the season

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Tate’s Van Gogh and Britain is, inevitably, gloriously, the London show of the season. Twenty writhing, impassioned, solemnly joyful paintings and drawings from Vincent van Gogh’s last years make it so. The violent expressiveness yet desperate lucidity of such canvases never stales, and on their high colour and rhythmic free forms modern art is built.

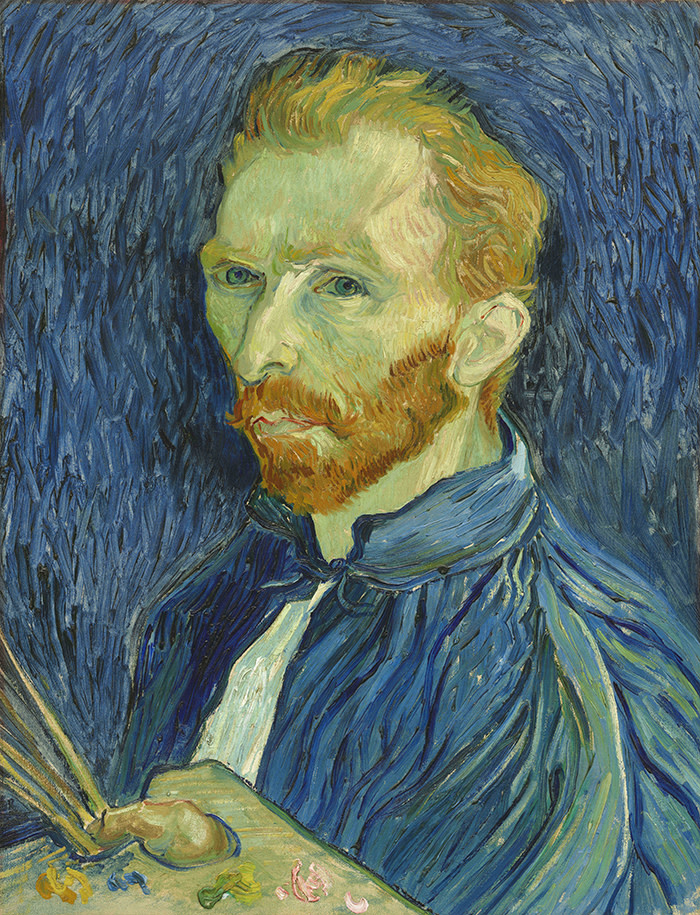

“Starry Night Over the Rhône” (1888), gas lights glimmering deep orange reflected beneath sparkling stars, with the river and sky whirling in thick strokes of ultramarine, cobalt and indigo, is a cosmic vision of nature at once consoling and full of dread. A year later, a gaunt face, “thin and pale as a devil” as Van Gogh saw it, stares out from ice-blue spirals in a “Self-portrait” painted in an asylum. “Hospital at Saint Rémy” depicts the view: twisting baroque trees against a darkening turquoise backcloth just pierced by what Van Gogh called “the gravity of great sunlight effects”.

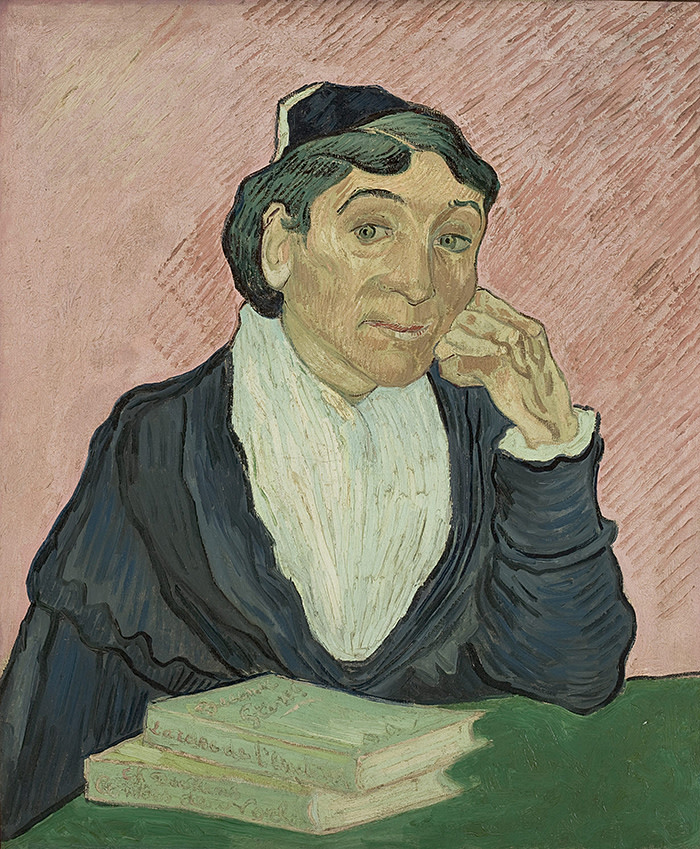

Returned to Arles in January 1890, Van Gogh depicted the work-worn, stoic patron of the Café de la Gare as a harmony of pink, green, white and black in “L’Arlésienne”, where he sought “colour as a means of rendering and exalting character”. He sent this to Gauguin, who answered: “You have never worked with so much balance while conserving the sensation and the interior warmth needed for a work of art.” Months later, Van Gogh was dead.

These four masterpieces visit from Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, Washington’s National Gallery, Los Angeles’s Hammer Museum and the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, and are emblematic both of the stunning loans achieved by Tate, and of the almost comically tenuous relationship with Britain claimed for them.

On the table in “L’Arlésienne” is a copy of Dickens’ Christmas Tales. “Self-portrait”, displayed in London in 1929, helped crystallise the legend of Van Gogh as tortured genius. “Hospital” is exhibited — the horror! — next to feeble Post-Impressionists Harold Gilman (“Tree”, “In Gloucestershire”) and Spencer Gore (“The Fig Tree”) to demonstrate how UK artists “adapted Van Gogh’s brilliant colours, distinct brush strokes and angled compositions to create British versions of his subjects”. “Starry Night” hangs in a gallery entitled Black and White: Becoming a Painter of the People, because its “urban perspective . . . can be seen in the context of imagery of the Thames”. It can’t: the picture is unequivocally Provençal, inspired by Van Gogh’s observation on arriving in Arles that “often it seems to me night is even more richly coloured than day . . . the starry sky . . . keeps haunting me”.

Why construct a show around such skewed connections? And do they matter? This is Tate’s first Van Gogh exhibition since 1947, and staging it at Tate Britain necessitated a British theme. As often here, the display blends biography — recounting Van Gogh’s London stay in the 1870s as apprentice picture dealer, then minister/teacher — and art history, tracing his impact on British painters.

The first is intriguing, the second orchestrated with catastrophic misjudgment, but the show soars anyway on Van Gogh’s urgency and conviction. Ineluctably his drama unfolds: how, long after his London years, this confused young man in less than a decade taught himself to draw, assimilated every contemporary innovation, and emerged as a pioneer of modern expressive painting.

The freshness of many loans gives this familiar story potent charge. From private collections come the symbolist, linear avenue with elongated black figures “Alley Bordered by Trees” (1884); the breezy “Bois de Boulogne with People Walking” (1886), painted in Paris as Van Gogh engaged with Impressionism; the cropped majestic “Trunk of an Old Yew Tree” (1888) against brilliant yellow, the stark composition influenced by Japanese prints. Here alone is a marvellous, condensed lesson in Van Gogh’s development, bursting from northern darkness to sunny southern liberation.

The London contribution to this tale is minor but well told. What did Van Gogh see and remember here? Tate’s earliest painting is his favourite piece at the National Gallery, Meindert Hobbema’s “The Avenue at Middelharnis” (1689). Its flat expanse of land and distant church spire reminded him of home, and the Dutch motif of tree-lined path, implying life as a journey, always attracted him. It is there in his tonal “Avenue of Poplars in Autumn” (1884), featuring a woman in mourning as a pilgrim, and in the fragmented pines leaning towards each other in flamboyant disarray on a pink footway in “Path in the Garden of the Asylum” (1889).

Van Gogh never relinquished Dutch painting’s moral fervour, eventually believing “a new art of colour” offered salvation for suffering humanity. As an idealistic youth in London he loved George Henry Boughton’s medievalist “Godspeed! Pilgrims Setting Out for Canterbury”, on which he preached a sermon — “it’s not a painting but an inspiration” — and graphic art honouring working-class life. Gustave Doré’s engraving “Newgate Prison Exercise Yard” provoked his only depiction of a British subject: “The Prison Courtyard” (1890), painted while incarcerated at Saint-Rémy. It visits from Moscow’s Pushkin Museum and one wonders how it resonated in Soviet days: high brick walls overpower the canvas where 33 inmates, heads down, circle in defeated rote. A sunbeam catches the face of one, profile and blond hair lit up — Van Gogh’s self-portrait of spiritual isolation.

That singularity is what makes the second part of Tate’s project so difficult. Van Gogh influenced everyone, but who on the wall can stand up to his uncompromising intensity of vision? Not Tate’s vapid prewar British practitioners. I have never experienced at Millbank so visually tone-deaf a hang as the 1920s-40s winsome floral paintings by Winifred Nicholson, Frank Brangwyn and Christopher Wood alongside Van Gogh’s ecstatic, mortality-infused blooming/dying “Sunflowers”.

Much proceeds in this vein: the juxtaposition of “Madame Augustine Roulin (Rocking a Cradle)”, all singing hues, simplified contours, lilting arabesques, with Vanessa Bell’s dots-and-dabs “Roger Fry”. “A similar sense of beatitude”, says Tate. But Bell, smug, facile, entirely derivative, was declaring her new Bloomsbury lover; solitary Van Gogh trying “to paint men and women with that something of the eternal which the halo used to symbolise, and which we seek to convey by the actual radiance and vibration of our colouring”.

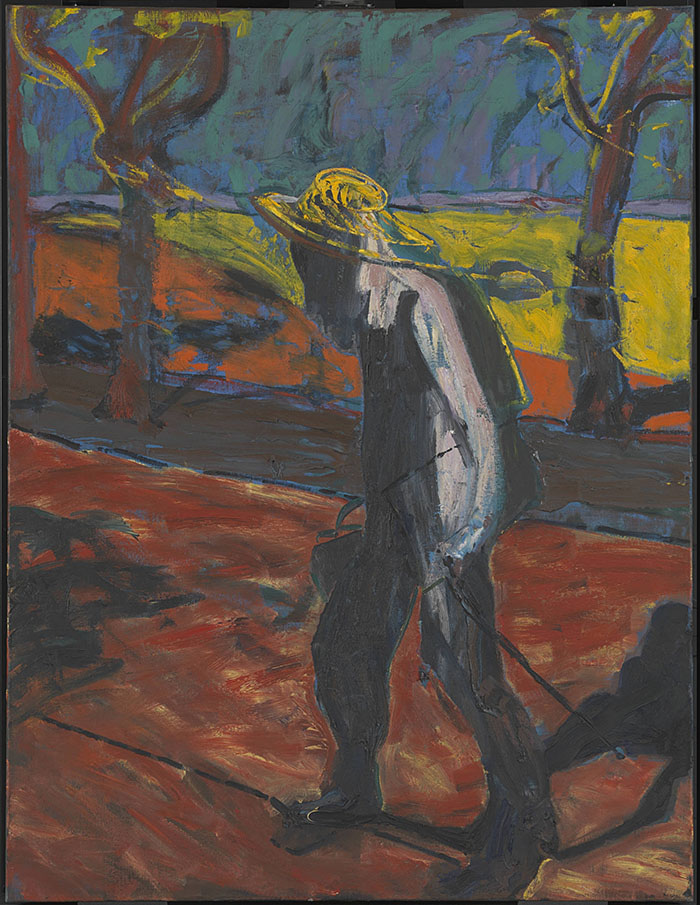

The show recovers at the end, where the prophet of Expressionism meets art’s priest of painterly existentialism — monumental canvases from Francis Bacon’s great series “Study for Portrait of Van Gogh” (1957). Based on Van Gogh’s “Painter on the Road to Tarascon”, these resonate with images of the tree-lined pilgrim road at the show’s start, while expressing postwar ideas of man walking, alone, spiritually anguished. It is a spectacular conclusion to an uneven but unmissable exhibition.

To August 11, tate.org.uk

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments