A conversation with Alice Cooper

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Let me tell you: a conversation with Alice Cooper is a counterintuitive experience. Not least because it is not something you expect will ever feature in your remit as a How To Spend It editor. The Godfather of Shock Rock. Begetter of the childhood anthem of the American ’70s, “School’s Out”. A man famous in part for regularly enacting having his own head severed onstage, then serenading it. Clearly there will be no besting this in my career.

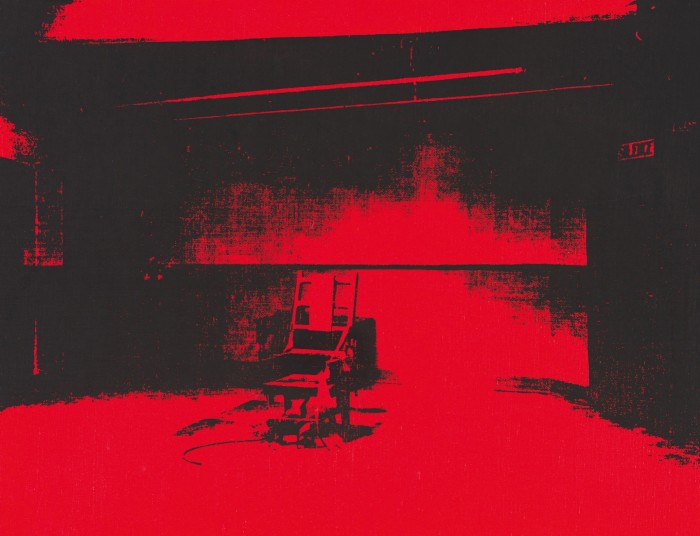

Our conversation has come about because Cooper is shortly to auction, for charity, a work by Andy Warhol – a 1964-65 silkscreen called Little Electric Chair, from the artist’s 1962-65 Death and Disaster series. Cooper is, in fact, a modest collector of art, and himself a sometime painter, as well as a committed philanthropist. He also plays golf. A great deal of golf – at least nine holes a day, six days a week, no matter where in the world he is – and boasts a handicap that toggles between four and five. His default course is a private country club, of which he is a member, founded in 1899 in an affluent Phoenix neighbourhood not far from the one where he lives in a tasteful, sprawling compound-like residence. Yes, this is the same Alice Cooper whom MP Leo Abse attempted to have barred from entering the UK in 1973, citing the performer’s “incitement to infanticide and his commercial exploitation of masochism”, which Abse characterised as “an attempt to teach our children to find their destiny in hate”.

He is speaking from the aforementioned home, in Paradise Valley, Arizona, the state in which he was raised and to which he returned post the mayhem of his peak performing-recording years. He’s seated in front of a panel of swirling colour laid over with abstracted graffiti – one of the backdrops for his stage shows, he explains; legendary sets that are equal parts cabaret-burlesque, horror show and full-on stadium rock event, and replete, still, after more than five decades on the road, with old-school pyrotechnics and lurching Cyclops, live pythons and many, many codpieces. Sans eye make-up, but very much in possession of his signature blue-black mane, he speaks eloquently and thoughtfully, smiling widely and often. His hands are mostly loosely clasped in his lap, but his eyebrows articulate volumes.

Behind his right shoulder is a sculpture of a giant human eyeball, in the palm of a hand whose arm functions as a pedestal; the eyeball is crowned with a tuft of neon hair. It too is part of the stage set; apparently there’s another one just off camera. “I go around and find the most bizarre things I can for Alice’s performances,” he tells me, occasionally dissociating from his stage persona by speaking about him in the third person (“Alice hates golf… if you put golf clubs on stage, he’d think they were weapons”).

“They are very Roger Corman,” Cooper asserts of the eyeballs.

A totally AC thing to say, read my notes.

“My grandkids love them.”

Ah; right. At 73, Cooper has been married for 45 years (to dancer and choreographer Sheryl Goddard; she played the sadistic head-severing nurse in his ’70s stage performances) and sober for 38. He has two daughters and a son and four grandchildren. The family often gathers at the Paradise Valley house; during lockdown, they spent several months together there. In its various spaces hang works by locally and nationally renowned artists: a few canvases by Anne Coe; several photorealist shopfronts, motels and neon signs by James Gucwa. In the past there were pieces by the late Larry Rivers – like Cooper, an artist/musician/occasional actor – in the mix. More recently, there was the Warhol, too. That story starts in Manhattan in the early ’70s: “My girlfriend [the late model and sometime Interview cover girl Cindy Lang] hung out at The Factory, so of course I saw Andy all the time, at Max’s Kansas City and clubs like that.

“I was using an electric chair in my show at the time.” He pauses, considering. “Though we were electrocuting less than we had been – by then we were moving on to hanging, and then the guillotine.” As one does. “Cindy had seen his series, and knew what I was doing in the shows, and just put the two together and thought, ‘That’s a perfect birthday gift for Alice.’”

I ask him if it’s true that she paid a mere $2,500 for it. “You know, I think it was actually $2,200…?

“Anyway, we hung it in our apartment for a while. And then I moved to LA and we broke up, I took it with me, and later my wife and I had it in our house in Beverly Hills. And didn’t really think much about it. To be honest with you, I wasn’t a real Warhol person. So when we moved back to Arizona, we rolled it up in a shipping tube, with a bunch of other art, and put it in the garage.”

In the intervening period, it hardly bears saying, Warhol’s work appreciated astronomically: in 2013, another, more important serigraph from the Death and Disaster series, Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster), sold at auction for a whopping $105.4m, setting a new record price for his work. A Little Electric Chair from the same series that Cooper’s belongs to sold for $10.46m at Christie’s a year later; in 2019, a second one fetched $8.22m. Is it also true, I ask Cooper, that his own Warhol remained in its tube for… decades? “Yeah. Yeah, I forgot about it for about 30 years.”

Rumour has it that it was Dennis Hopper who reminded him of the work’s existence. “OK, so [several years ago] I took my daughter Calico to the Kentucky Derby, and we did the whole Derby thing, we were sitting in a box with Dennis and, you know, P Diddy and a bunch of other people. And Dennis started going on about how he had just sold one of his Warhols” – a screenprint of Mao Zedong (embellished with bullet holes, added when Hopper came home one night in a drug-fuelled fury and fired two shots into it; they were later annotated by the artist himself), which netted just over $300,000 at Christie’s.

“A lightbulb went on. I thought, ‘Wait a minute: I have an Andy Warhol. Where did I put that…?’ So after the Derby I went back to the house and I found the tube, and I pulled it out and it was in perfect condition.” For a few years, the silkscreen hung in his house. “Then I talked to my manager [Shep Gordon] and said, ‘I’ve got this piece of work, I’m not a Warhol collector. Let’s, you know – let’s do something with it.’” Eventually they decided to sell it at auction, with a percentage of proceeds going to Solid Rock, the non-profit foundation that Cooper, his wife and his longtime friend Chuck Savale set up for disadvantaged and at-risk teens.

Solid Rock was created in 1995; the first bricks-and-mortar centre, a 28,000sq ft facility, opened in downtown Phoenix in 2012, after more than a decade of fund-raising on the Coopers’ and Savale’s part. A second centre, in the city of Mesa, was inaugurated in 2020. “You know, I watched a very awkward drug deal go down a long time ago between two 16-year-olds who didn’t know I was watching. I thought, ‘How does that kid know – how do we know – he isn’t the best guitar player in town? And that other one, the best drummer?’ Because they’ve never had the opportunity to find out. That wasn’t an option for them. What if they had that option?

“Solid Rock is a place that wants to give a kid an opportunity to come in and find out what he’s good at. We want to break the cycle of what [at-risk] kids are programmed to do. All of a sudden, being in a band is much more exciting than being in a gang. And then they’re all there, every day, right at three o’clock.”

Beyond music, Solid Rock offers photography, cinematography, writing, dance and other performing-arts and theatre studies – both instruction in the fine-arts aspects and vocational training for the more technical work. (“We get kids who maybe aren’t musically inclined, so they go into the studio instead. They know how to work everything by the time they’re 14; they’re doing Pro Tools like it’s nothing.”) His daughter Calico, an improv comedian who studied with The Groundlings comedy group, helped set up a black box theatre at Solid Rock. Cooper tells me that Johnny Depp, with whom he performs in a cultish side project called Hollywood Vampires (its third member is Aerosmith’s Joe Perry), has volunteered to come in and teach.

After discussing selling Little Electric Chair via a major New York auction house, Cooper opted to do it at a local Scottsdale, Arizona gallery called Larsen. “Shep said, ‘Look, it’s an international auction.’ But we’re here, and we’re from here. Scottsdale is pretty high-end, and Phoenix is one of the biggest cities in America, and people can bid online.

“There’s probably some Warhol collector out there who’s been looking for a red Little Electric Chair forever. You know – they’ve got the yellow one, and the green one, and they’re compulsive and have to have the red one. And for me, it’s just… hanging in my house. Maybe I’ve had it most of my life and it’s not as exciting to me as it is to someone else.” Cooper’s compulsion is cars. “Like, if I saw a ’63 Studebaker, or a [Pontiac] Banshee, man, I’d kill for that car.”

Cooper’s modest demeanour and folksy rhetoric belie the fact that he has always brought real artistic intention and nuance to his work: songwriting, performance, stage design and acting (please do yourself a kindness and watch the various segments from his 1978 Muppet Show appearance, then admire him all but stealing Wayne’s World out from under Mike Myers with his extemporaneous disquisition on the indigenous history of Milwaukee, delivered backstage after a gig). He has engaged with art, and being an artist, his entire life, from the days when he was still known as Vincent Furnier and studying it at Cortez High School, Phoenix. “Art and music are both, to my mind, very mathematical – which funnily was my weakest point in school. When you’re writing a song, you have so many measures and so many syllables. You have a melody line, and you have to make it rhyme and tell a story. You have to somehow fit in the punchline.” The structure and attention, he says, are how the perceived balance is achieved. “And for me it’s exactly the same thing with art.”

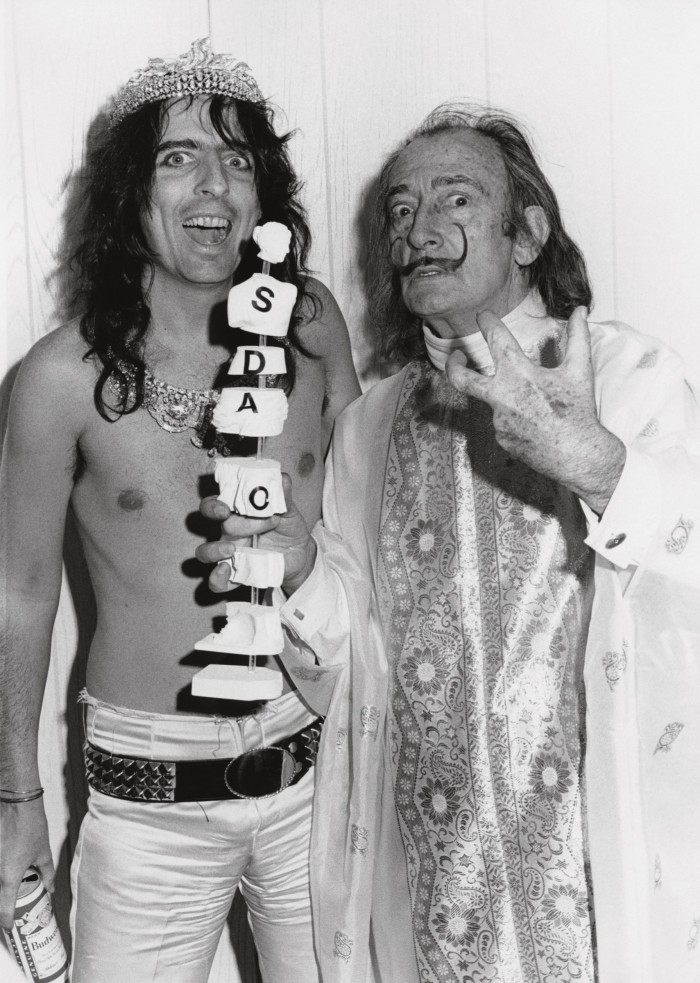

He notes also how much – of music, of art, of performance – is in the eyes of the beholder. “Everything was art to Andy. You know, the Campbell’s soup can, things we see every day. But suddenly as art, it becomes something you appreciate in a whole new way.” Students of the Cooper oeuvre will know he has long been intrigued by Surrealism. “I collaborated with [Salvador] Dalí once,” says Cooper. “Yeah, it was pretty amazing. I was always a fan – I mean, his paintings were just insane, but he was also one of the great realists in oil.”

In 1973, Dalí invited Cooper to the King Cole Bar at the St Regis in New York, having seen one of his stadium shows. He proposed a collaboration: a performance-style piece that would be recorded via hologram, featuring his own ceramic sculpture of Cooper’s brain (which itself featured a melting chocolate éclair and ants. Naturally). First Cylindric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain can today be found in the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Spain.

“Groucho Marx saw my show as vaudeville, a sort of dark-humour vaudeville. Dalí saw my show and perceived it as surrealism,” Cooper continues. “But you have to remember that everything was about Dalí. I, we, were just an extension of him.” He smiles. “In all honesty, we kind of were. He was the most interesting character I think I’ve ever worked with.”

Apart from, one assumes, the reviled, beloved, inveighed against, respected and totally counterintuitive Alice Cooper.

Little Electric Chair, 1964-65, a work in acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas, will be auctioned, live and online, on 23 October at 10am Mountain Standard Time. Visit larsenartauction.com or larsengallery.com, or call +1480-941 0900

Comments