The punk philanthropy of Libbie Mugrabi

Simply sign up to the Fashion myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

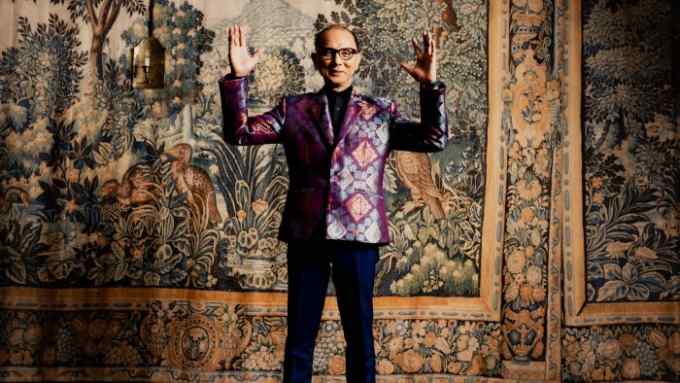

It was natural to Libbie Scher Mugrabi that she should end up sponsoring the V&A’s Fashion in Motion programme, which stages catwalk shows by designers in the museum’s hallowed halls. “I’m always in motion,” says the 42-year-old New Jersey native hitherto mostly known for an eye-wateringly expensive divorce. “I can’t sit still. I’m compulsive, and I love fashion. It just kind of reminds me of myself: like, ‘Fashion in Motion!’”

Mugrabi’s involvement with the V&A, a three-year engagement that began in July last year, does have something of the fairytale about it. On the one hand, it’s the millionaire sweeping in to save a programme put on hold by the pandemic; on the other, it’s about said millionaire transforming herself from gossip-page titbit into munificent patron. Her separation from art-dealer scion David Mugrabi, whose family are known to own the biggest private collection of Warhols in the world, was dubbed by one socialite New York City’s “nastiest” multimillion-dollar divorce. Inevitably, a Warhol was at the centre of one domestic fracas when the 10-year marriage ended in 2018, while a Keith Haring sculpture was the source of another tussle – quite literally so.

This is now in the past; the couple have sorted custody of their two teenage children and Mugrabi has a settlement of approximately $100mn. Sitting in a booth in London’s Brown’s hotel, tanned from her regular séjours in Miami and Maui, clad in sleek black Balenciaga and Loewe topped off with one of her own signature customised trucker hats, Mugrabi is keen to set out a cleaner, clearer vision of her future. Also, to shop. She is, apparently, “the biggest customer of Balenciaga in Miami”. The house values her custom so much, she claims, it flew her to Paris for its latest couture show. She loves its creative director Demna, whom she considers a good friend, and she loves his aesthetic.

“It’s not straightforward fashion – it’s more playful,” says Mugrabi, who is alternately dreamy, chatty, even childlike. Of the five suitcases she has brought with her to London, where she has come to see the latest Fashion in Motion show by the Johannesburg-based designer Thebe Magugu, one is filled with oversized jeans, another contains just caps, and another only lingerie. “I like either really tight clothes or really oversized clothes. I don’t really like grey areas.”

Mugrabi had never been to the V&A until 2020, when she flew over to London, at the height of the pandemic, in a hazmat suit. She was given a walk-through of its Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk show by director Tristram Hunt and they took a picture. Call it fate: “My whole outfit was matching the museum.” Six months later, on her birthday, Mugrabi received an email asking if she’d consider “taking over and funding the programme, because they were going to cut it” (V&A simply says that the programme was “on hold”). “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, really?’ And then I was like, ‘Wow – I could do that.’”

Thanks to Mugrabi’s cash – a figure she can’t disclose, but which she says is “six digits a year” – Fashion in Motion has been able to stage accessible catwalk shows by names such as Harris Reed and Daniel Lismore. “The series displays fashion as it is meant to be seen – in movement,” says the V&A’s senior curator Oriole Cullen. “We are extremely grateful to Libbie for her support… which has enabled us to realise the full potential of these free-to-attend live fashion shows.”

For Mugrabi, meanwhile, the chief joy of the gift is “just platforming young designers and artists”. She has no creative input on which designer is asked to take part; instead, she thinks her main contribution, other than the money, is to get the programme (which started in 1999, and has also showcased Philip Treacy or Alexander McQueen) better known. “I thought that if I was going to be involved with something, it should be publicised and people should know about it,” she shrugs. “It’s not a secret society.”

It’s also a way of embedding herself further in the fashion world, where she plans to make a coup by launching her own clothing line next year. Yes, it will feature her caps, of which she has hundreds at home, all customised with glitter and capital letters in one of her two “Libbie factories” (a studio adjacent to her bedroom in New York, and another in a converted garage in the Hamptons), but also a line of unisex streetwear. The night before we speak Mugrabi went to the London club Annabel’s and was incensed when they asked her to remove the signature headwear. “I don’t know why I can’t wear a cap in Annabel’s, because I see what a lot of people wear there,” she tuts. “My idea is to change fashion – and to make things acceptable that are not acceptable.”

In fact, Mugrabi doesn’t think of herself as a designer so much as an “artist” – a “visionary”, even. And she has done so for a long time. “I knew when I was 15 that I was going to be big in the world,” she says. “I knew when I was two.” Born into a wealthy family, Libbie Scher had her own pedigree well before she met the Mugrabis. Her grandmother was one of the first five women in New York to take the bar exam; her grandfather was a “pioneer of plastic surgery in America” (noses and chins). Her aunt was “a Hasidic Jew who took off her wig and appeared on the cover of fitness magazines”. Very little of her own career trajectory therefore feels unusual. “I’m the most eccentric person in New York!” she announces. But she’d like to be more independent.

“I am independent already,” she continues in that distinctive New Jersey drawl. “But I’d like to be completely independent, with no one ever to tell me that they did that for me.” Yes, she likes being in the room with the “big boys”, she says gleefully – “my ex-boyfriend ran for president”. (She had a romance with crypto entrepreneur Brock Pierce, who ran as an independent candidate in the 2020 US elections.) “I liked being in the room with all the people there… But when I’m doing my own thing, I don’t want too many boys around me!”

When the V&A asked Mugrabi if she would subsidise the programme for 10 years, she chose to start with three. She was following the advice of a friend who, following her divorce, had given her a three-step plan as to how to get her life together. He told her to “go on the boards of museums, like the Tate or the V&A; start a lucrative business; and start a foundation”. She has since put all three in motion, but there are downsides. She relays a phrase often heard in her circles – “bored on the board”. “It’s the worst,” she sighs. “My friend explained it to me when she was on one. She said, ‘What a job this is, Libbie! They call you up, all these people, they beg you for favours, and you have to pay to be there. And then, if you can’t get the favour, people are mad at you.’”

Does she feel responsibility because of her wealth? “Of course!” She likes to give her money away – “money is energy.” She doesn’t like it to stagnate. “People help others because it helps them. There is something selfish about it – well, not selfish, but generally when you do something good for humanity, you feel good about yourself.” It is, she points out, a part of her Jewish faith to give a percentage of her earnings to charity. “In my religion, when you do anything good, it’s called a mitzvah. And my aunt calls me a mitzvah girl.”

On which note, she repeats that the best way to raise money, really, is a gala. “People want to feel part of something. It’s much easier for them to buy a table for a gala than it is for them to write a cheque.” But this is the source of a bone of contention. She’d like to host one for Fashion in Motion, but it hasn’t happened yet. “They seem overwhelmed by the idea,” says Mugrabi. “And I don’t want to upset anyone.” However, she suddenly announces that if, by the end of the three years, she can’t do one, she’ll make an exit. “I’m gonna start my own fashion programme, and do my own gala – in my own museum!”

Mugrabi has only barely started to create her legacy – although she might need some help with the finer details. “I’d need somebody to work on the computer,” she admits. “I don’t do that.”

Comments