Inside food’s new Silicon Valley

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The dish looks like any course you might expect to find at a high-end restaurant in Copenhagen: a speckled, ceramic bowl with two half-moon-shaped dumplings, filled with squid and spiced sausage, delicately placed in a pool of zingy lemongrass broth. The dumplings look fabulous, but there’s more to them than meets the eye. Rather than just using regular flour, they’re also made from a byproduct: fish bones. “Instead of throwing [the bones] out, we process them into a fine ‘pulp’, then use that to create a dumpling dough,” explains Matt Orlando, chef and owner of Amass, the restaurant responsible for dreaming up the dish.

This is just one example of the many innovative dishes being cooked up in Copenhagen’s kitchens, a reaction to our dire global food situation. An estimated one third of all the food produced for human consumption globally is wasted and eight per cent of countries’ greenhouse gas emissions come from growing food that isn’t even utilised. Worse still, research has shown that industrialised farming, which produces vast greenhouse gas emissions and pollutes air and water, costs the environment the equivalent of $3tn every year.

In Copenhagen, a city now considered the epicentre of food, there’s a new movement brewing where like-minded producers, chefs and innovators are coming together not just to share ideas but leftover products too. It’s become, if you will, the Silicon Valley of the food world: a testing ground for solutions to food waste, recycling of waste products, cooking in a more responsible way and even promoting regenerative farming.

It comes hot on the heels of the New Nordic food manifesto formulated in 2004 by chefs from Denmark to Iceland with a focus on hyperlocal, seasonal ingredients, with the success of René Redzepi’s Noma responsible for catapulting Copenhagen cuisine onto a global platform. “We’re all children of the manifesto,” says Martin Marko Hansen, head of innovation and sustainability at Jalm&B, a large format bakery that is looking for new solutions to utilise wasted bread. “We’ve created a community where we’re connecting over ingredients, having meetings and brainstorming with other like-minded people.”

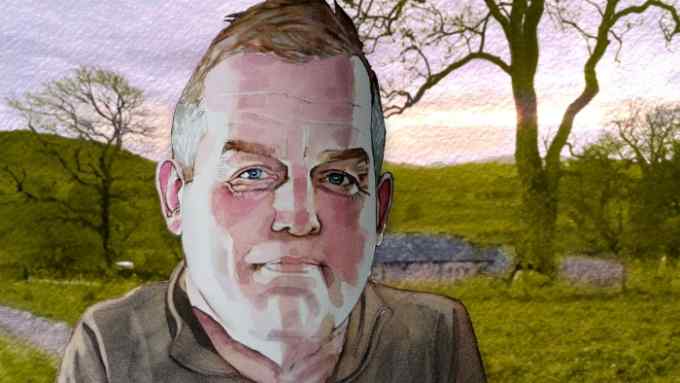

This New Nordic 2.0 could become a leading example for how to rethink our food system. “Hopefully, it will set the stage for restaurants to operate more responsibly,” says Orlando. Amass has become a leader in responsible dining. Since the 90 to 100 per cent organic restaurant opened in 2013, it has reduced its rubbish by more than 75 per cent, its annual water consumption by 5,200 litres, and grows many of its ingredients in its waterside urban garden. “Amass is a platform for us to prove that you can do this without compromising on anything,” says the former Noma chef.

Other chefs and restaurants have followed suit. At Il Buco, restaurateur and food pioneer Christer Bredgaard has been working to reduce waste and cooking nose-to-tail-style for over 10 years. “It’s nothing new, really. It’s an old-school way of cooking in general,” he says of the zero-waste food movement. “I don’t think we are there yet, I don’t think anybody is. But it takes a lot to be consistent.” At Il Buco, leftovers are fermented and scraps from their in-house bakery are fed to pigs, which are then slaughtered and sold back to the restaurant. The chefs use the entire animal, including the pig’s heart, liver and lungs which are blended into a terrine served on the charcuterie plate. Bread, which is one of their biggest sources of waste, has been sent to their friends at Braw brewery who brew beer with sourdough leftovers. “Our take on the tiramisu has only one non-Danish ingredient, which is spent coffee grounds,” explains Bredgaard, who infuses a creamy house-made mascarpone with the grains, using chicory root – also normally a byproduct – as part of the top of the dish.

At Tèrra, a small restaurant that also aims to create a circular economy, everything is reused and transformed into byproducts until only fibres or bones are left, which go to organic waste. One plate featured the usually undesirable gar fish tail, which is glazed with tamari, barbecued and then served with an umami broth made from the fish bones and head (which, once used, go into the compost for the kitchen garden). At first, diners were shocked to see a shiny red fish tail set in front of them, mid-tasting menu. “Especially because we were doing this in a fine-dining style,” says co-owner Lucia de Luca, who must engage diners on the topic when they are presented with the menu. The restaurant soon won them over and the dish remained on the spring menu.

To further the commitment to being more responsible, a handful of restaurants have signed up to Zero Foodprint Nordic, launched earlier this year. It’s a crowdfunding system where restaurants add one per cent to diners’ bills that goes to the non-profit’s regenerative farming partnerships. “The whole idea is that restaurants take action by using their cultural capital to influence,” says founder Cindie Christiansen. “It also gives the customer a chance to be part of the change.”

Beyond restaurants, there’s a group of innovators creating ideas out of byproducts like spent beer, coffee grains and old bread. Considering just one quarter of the food currently lost or wasted globally could feed 870 million hungry if saved, the impact of these solutions could be major.

At Amass, Orlando launched a new research space during the pandemic, which works with large food-producing companies to identify their waste streams, then develops processes to pivot these byproducts into something tasty they can resell. “If you’re creating a food product that’s based on this way of thinking, it has to be delicious no matter what,” says Orlando. “You can do as many sustainable things as you want but unless they’re delicious they will not move.” For Orlando, this was the obvious next step for his restaurant. “At Amass we do 50 to 60 guests a night, which is not a lot of people to reach with your message. How do you make a restaurant have more substance than just that?”

One such example is the result of a collaboration with Jalm&B, where the Amass research space has developed a salty sourdough caramel, chocolate-dipped ice cream produced with syrup extracted from the bakery’s surplus bread. “We’ve created a process that enzymatically changes the starches and the leftover bread to sugar,” says Orlando. The ice cream, which is served at Amass but also sold in supermarkets around Copenhagen, is an example of how these products are also becoming more accessible. “It’s not the solution for all problems but it’s one step towards more sustainable choices,” says Martin Marko Hansen. The hope is that bigger producers will look their way, make these products at a larger scale, and ultimately lower the price and use more surplus ingredients.

“Any kind of food innovator I meet in Copenhagen is working with some kind of byproduct,” says Ebbe Korsgaard, CEO of Beyond Coffee, a startup that grows mushrooms from used, organic coffee grains, collected en masse from companies and office buildings.

The hope is that eventually these food solutions will cross borders too. Agrain, which upcycles spent grain from beer and whisky production into familiar products like crisps, flour and granola, is tapping into an unknown resource that is widely available in most countries. In fact, an estimated 40 million tons of spent grain is produced (and thrown away) globally every year. “In a world where we will soon be living with food scarcity, it doesn’t make sense to throw out such a good resource,” says Aviaja Riemann-Andersen, co-founder at Agrain. Considering quantitative food waste per year is roughly 30 per cent for cereals, the granola is a game-changer. It’s also delicious. One flavour is made from a chocolatey stout supergrain with powdered rose hip and blackcurrant, making it naturally sweet and crispy.

But the brand doesn’t just refuse to compromise on flavour (the products are tested by chefs like Matt Orlando) but on accessibility too. More recently they worked on a project with East African Breweries in northern Kenya, where they analysed the brewery’s spent grains to see if their method could be adapted to sorghum-based beer to create nutritious flours to replace ones usually sourced outside of Africa. “From this brewery we could supply 400,000 children with a yearly need for protein,” says Riemann-Andersen.

While these are all bold steps in the right direction, Christian Puglisi, long-time food activist, chef and owner of Bæst and Mirabelle restaurants and the organic Farm of Ideas, doesn’t foresee long-term change without support from governments. While he can’t deny the value in what chefs and startups are doing in Copenhagen, he sounds a note of caution. “Sometimes we get so caught up in the chefy world of reusing things that might be wasted, but they essentially have so little nutritional quality,” says Puglisi, who has been challenging the food industry since his pioneering restaurant Relæ became the first Michelin-starred 90 to 100 per cent organic restaurant in 2013. Other than committing to supporting good local producers and growers, his most sustainable solution would be the repurposing of proteins as feed for livestock. “But by legislation it’s completely impossible.”

Puglisi’s argument is that if we can’t change legislation (and quickly), we won’t be able to implement sustainable improvement. And he’s not wrong. But then again, every norm was once a trend and if we want to change our entire food system we at least have to try to find meaningful solutions that might stick. “This is a cultural shift,” says Orlando. “In the sense of how people perceive the food system and perceive food in general.” His thinking is that if we can start planting those seeds, governments will have no choice but to listen to people a couple of generations down the road. “We can’t just give up and say, ‘Oh, it’s never going to change.’”

And that change needs to happen beyond Denmark, a country with only 5.8 million people. The ultimate goal is for these tried and tested solutions to be transported globally. “We have a responsibility. If we can do things here and prove that they work on a scale, then hopefully these things can be taken into countries of tens of millions of people and applied,” says Orlando. But time is pressing: “We need to invest in this now.”

Comments