Jane Dickson, the ‘painter of American darkness’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Bushwick, Brooklyn is a mishmash of new developments and historical remnants. Once home to immigrants from Europe, then Dominican and Puerto Rican communities, over the past few decades artists have flocked here, transforming the industrial buildings into live-work studio spaces. Past industries – from glass and chemicals to beer – peek out via heritage architectural elements and weathered painted signs, but it’s hard to find prewar buildings intact. Jane Dickson’s studio is located in a carriage house tucked behind one such remaining, a beautiful brick house from 1891. Although modernised to meet the needs of the painter, it feels old New York.

With her silvery curls and effervescence, Dickson seems softer in person than one might imagine of the artist dubbed “the painter of American Darkness” by her friend the artist Nan Goldin. She prepares two cups of matcha tea and we sit in the studio, surrounded by her paintings – most oil or oil stick on both canvas and non-traditional surfaces such as Tyvek, vinyl and AstroTurf. Soon, the new paintings will be sent to London for Dickson’s first show in the city for more than 20 years, at Alison Jacques gallery, commanding prices ranging from £25,000 to £90,000. The exhibition follows her inclusion in the 2022 Whitney Biennial Quiet as it’s Kept, and precedes another solo show in September at the East Village gallery Karma.

Now 70, Dickson moved to New York City from Chicago (via art schools in Paris and Boston, and a degree in visual and environmental studies at Harvard) in the late ’70s, at a time when counterculture music, art and performance were at their peak. It’s the world that still fuels her painting practice. She and her now-husband, filmmaker Charlie Ahearn, became regulars at The Mudd Club in Tribeca, an epicentre for the underground scene, where she forged relationships that led to profile-raising shows with Collaborative Projects (commonly called Colab), a group that included artists such as Kiki Smith, Tom Otterness, Christy Rupp, Walter Robinson and Jenny Holzer. “[We were] the oddballs, contrarians, utopians – questioning all the rules and experimenting with ways to reformulate that world,” explains Dickson. Together, they were determined for “artists not to give away all control to the cultural gatekeepers… We made our own shows outside of designated art spaces – to have a say over the conversation, what view could be presented and who could present them. It was an outsider, adversarial stance.” It cemented Dickson’s place as an artist’s artist.

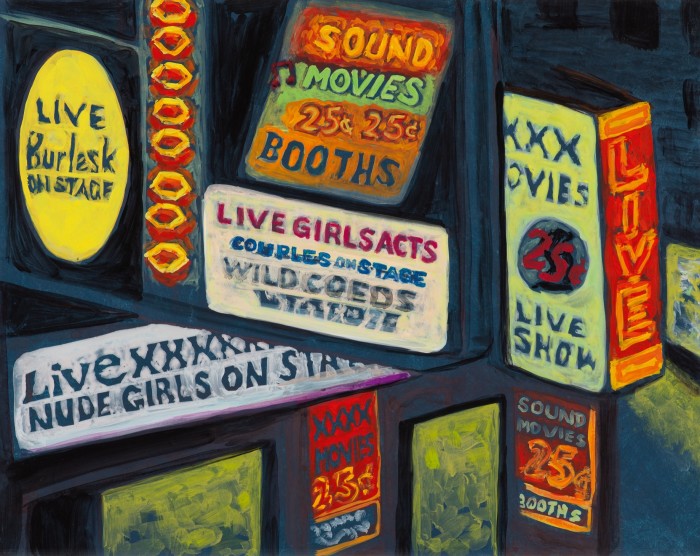

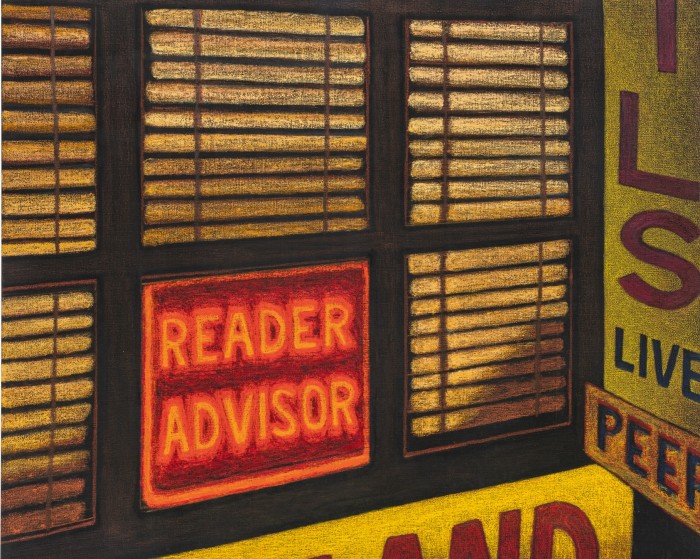

The London show, Fist of Fury, features a series reinterpreting photographs of New York City’s Times Square at night in the ’70s and ’80s. The exhibition takes its name from a Bruce Lee film on a marquee that Dickson included in a painting, and an attitude: “I wanted to paint things that I was afraid of,” explains Dickson, who has drawn on the mood of the area, at a time when violence was at a high. “As a young woman, the nights were a fraught space. I wanted to prove that I was brave, and while making a painting doesn’t stop the possibility of somebody mugging you, [I used] art as a way to overcome my fears. I was like, I’m going to occupy where I am and not be timid.”

Times Square has always exerted a magnetic pull on Dickson. Soon after she arrived in NYC, she got a job as a designer at Spectacolor, the first digitally animated lightboard on the square, where she worked the night shift and gave airtime to artists including Jenny Holzer, Keith Haring and David Hammons. Not too long after, she and Ahearn moved to a loft nearby, on 43rd Street. Back then, Times Square was almost frozen in time as much of it awaited demolition, creating a playground for illicit activity but also for artists looking for space to work. “[It] looked like the ’30s, like an [Edward] Hopper painting,” explains Dickson. “And I knew that once they could, they would tear it all down and it would look like Sixth Avenue, which was already full of skyscrapers. So I thought, I’m going to document this. It’s what’s outside my window. But it’s not long for the world.” So began a life’s work of being “drawn to things that are more historic… than current”, rich with information and opportunity to excavate the human experience.

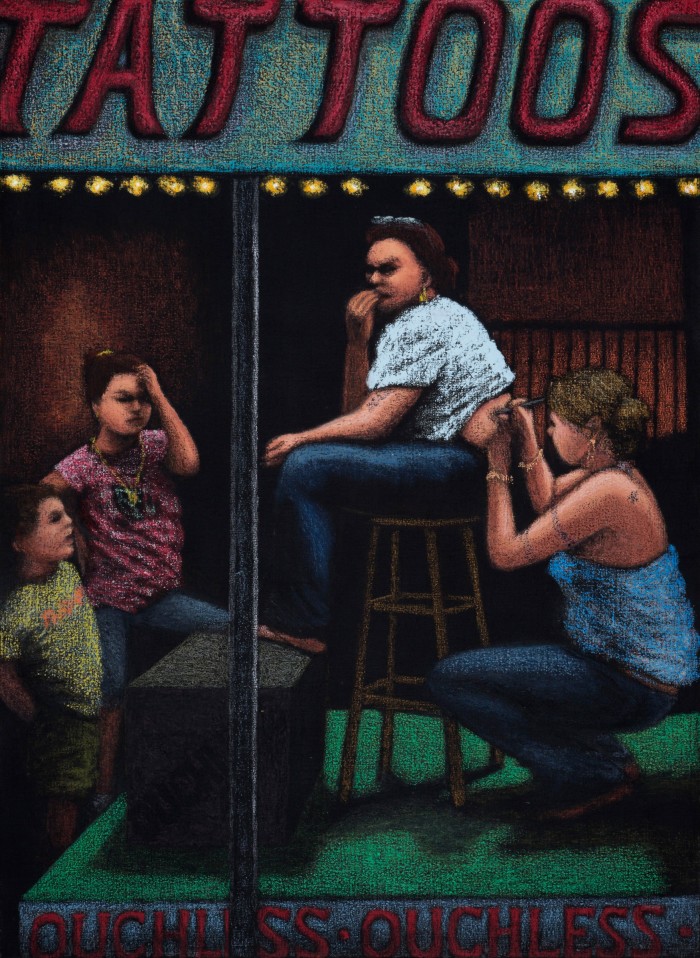

For Dickson, this seedy wasteland has become her defining oeuvre: cinematic paintings where darkness is uncovered by luminescent street signs above liquor stores and bars. With camera in hand, Dickson documented fleeting or sometimes dangerous occurrences as note-taking for her paintings. Her photography – which, to Dickson, are not artworks in their own right – features unknown subjects but also friends such as Goldin, Haring, Kiki Smith, Martin Wong and David Wojnarowicz. Mostly, she took these photos on the street or looking down from her loft window. At one time, she documented female subjects in strip clubs – hers was the intimate perspective of a woman who understood first-hand the “vulnerability of real experience”, as she describes it; an experience that could be empowering for the dancers (many of whom she knew), until it was not.

“Although Jane came to prominence alongside artists such as David Hammons, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jenny Holzer, I would say, at least canonically, her work is more in the lineage of [Edward] Hopper or [George] Bellows,” says Karma gallery founder and publisher Brendan Dugan. “Like them, she’s a painter attuned to an ever-present sense of loneliness in modern life.” Bellows, an American realist painter associated with the Ashcan School, resonates with Dickson: the artistic movement, she says, exposed a “thorny aspect” of the world “because it was about real life”.

In Dickson’s Big Peepland (2016), the viewer looks down at a man who has just stepped out of a strip club – the fiery palette of the signs echoing the glow of his cigarette. Is this illicit, sad or sexy? Dickson leaves it to the viewer. In some works, streets are almost empty save for a figure slinking across a street or standing in front of a bar; others feature drug deals, NYPD cops mid-arrest or voyeuristic views of city dwellers through their windows. The vibrant neon signs offer an evocative view into darkness. Like her reference photos, sometimes you’re seeing the scene straight on, as if you’re there, at other times from up above, like a Peeping Tom.

Dickson considers her paintings to be scenes from America but also psychological self-portraits. “When I was a kid [in Chicago], I remember looking out the window of a car when the city was dark at night and I thought, if I could just capture this, then my family would know how I feel,” she says. In a recent series of paintings of suburbia, Dickson not only unearthed and explored her own relationship with the urban outskirts but examined her feelings about motherhood as well. Parallels too, can be drawn with Dickson’s recent treatment for breast cancer. “I paint to find out what I’m thinking,” she says. “There are certain images that will resonate with me, and when I start working on them, often I will repeat them multiple times, like I’m excavating.” Says gallerist Alison Jacques: “The key for me is Jane’s use of artificial light. Be it fairgrounds, casinos, peep shows or life on Times Square, I saw these as works – much like the Spectacolor screen – as journeys in which atypical colour, [and] changes in tones, can change our relationship with a particular subject.”

Dickson’s darkness seems particularly to resonate at times, says Dugan. “There’s an enormous sense of impending disaster inherent to American life, especially for women, and Jane masterfully soaks her paintings in that sense of dread. Her subjects are ostensibly very simple – stairwells, neon exteriors, empty façades – yet it’s what she omits that’s most interesting. Figures are turned away or diminished under the veil of night-time.”

But even in the periphery of darkness, Dickson’s paintings offer a sense of opportunity – the possibility to reclaim power, exercise one’s own “fist of fury”. It’s time for such a powerful expression to have a resurgence.

Fist of Fury is at Alison Jacques, London W1, from 11 May to 24 June 2023, alisonjacques.com. Jane Dickson will show at Karma, New York, in September 2023, karmakarma.org

Comments