The work that remains to reach net zero

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Thursday

It has been a week of a lot of IMF reports. I covered the pre-released analytical chapters in the previous Free Lunch, and my colleague Martin Wolf devoted his column this week to the updated numbers released by the fund.

But more significant than all of these may be another publication somewhat drowned out by the flurry of reports. The International Energy Agency expedited the publication of its flagship World Energy Outlook to be out before next month’s COP26 climate conference. It is an excellent and comprehensive guide to thinking about where we are in the carbon transition and what remains to be done (see the FT’s news story here).

Earlier this year, the IEA had set the cat among the pigeons (at least oil-producing pigeons) by presenting energy market projections consistent with net zero global carbon emissions by 2050 that showed there was no room for investing in any new oil or gas exploration — existing reserves are enough to meet all the demand compatible with decarbonising by that deadline.

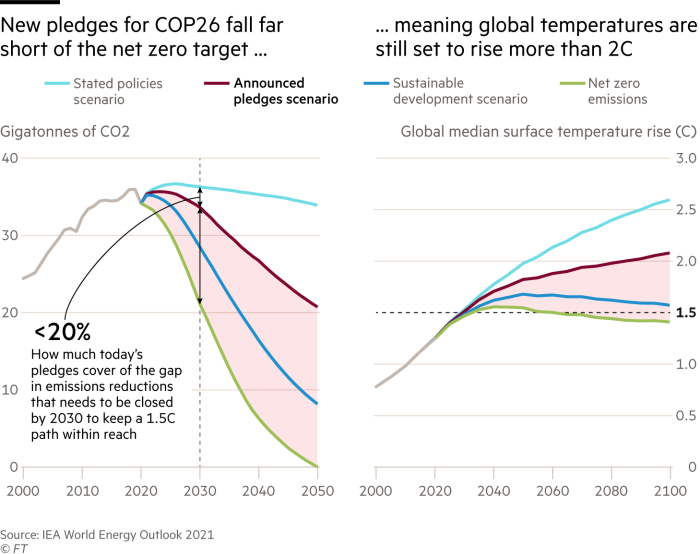

This week’s report focuses our thinking by comparing the net zero scenario with two other scenarios of how energy use and production will evolve. One is an “announced pledges” scenario, in which countries do what it takes to make good on the decarbonisation promises they have made so far. The other is a “stated policies” scenario, which looks at what countries currently do, not what they say.

The contrast between those two and the net zero tells a striking story: countries are at present not acting to achieve what they have pledged to do — but even if they do move from stated policies to announced pledges, that only gets them one-fifth of the way to the carbon emissions path of the net zero scenario. In short, an enormous amount of political and policy change still has to happen, much of it next month.

The IEA identifies four priorities: clean electrification, energy efficiency, methane reductions and innovation. The first two are unsurprising. The last two are perhaps less obvious, but the IEA brings the numbers to bear on their importance. On innovation, the agency says that while many of the needed decarbonisation technologies are already available, more investment is needed now for the technologies that will make a big difference in future decades:

“Governments need to step up support in key technology areas, such as advanced batteries, low-carbon fuels, hydrogen electrolysers and direct air capture. They also need to collaborate internationally to reduce costs and ease the path of new technologies to market . . . In the [net zero scenario], new technologies that have an important future role make vital early progress. Hydrogen-based fuels and fossil fuels with CCUS [carbon capture, utilisation and storage] make up just under 1.5% of total final consumption by 2030, up from almost nothing today. These relatively small inroads into the market prepare the ground for these technologies to ramp up after 2030 and make a bigger contribution towards net zero energy emissions by 2050.”

Here are six takeaways from the report I find particularly significant in terms of the economics and political economy of the carbon transition.

The report’s main findings have big implications for the politics of today’s power price crisis. By identifying clean electrification and greater demand-side efficiency as the top two contributors to getting to net zero, the IEA implicitly challenges policymakers who are now scrambling for ways to reduce electricity bills. For, as I argued in a recent column, the rise in gas prices, and the linked rise in electricity prices, are the best incentives there could be for both of these two goals. Policies such as price caps or windfall taxes that reduce the amount received by renewables generators, which otherwise benefit from high prices for the gas that competes with them, will lower the future return developers expect to get from expanding renewables. And lowering the price paid by consumers for the marginal unit of power blunts the incentive to economise on electricity use.

There are free lunches! The IEA estimates that 60 per cent of faster electricity decarbonisation can come at no extra cost to consumers because renewables are often already cheaper than the alternatives. It thinks 80 per cent of additional efficiency gains on the energy demand side could also pay for themselves by smart regulation (on such things as appliances standards and materials use). And 45 per cent of oil and gas methane emissions could be avoided at no net cost, “given that the cost of deploying the abatement measures is less than the value of the gas that would be captured”.

Energy use has to increase for the poor: 770m people globally still lack access to electricity, and this number went up because of the pandemic after a steady decline. Even if overall global energy use falls in the net zero scenario, it will increase in many of the poorest countries.

Conversely, energy intensity — the energy needed for any given economic output — has to accelerate. In the stated policies scenario, the IEA estimates that the amount of energy needed per unit of gross domestic product improves by 2.8 per cent a year. But that is not enough. For net zero, this rate of improvement would have to go up to more than 4 per cent a year, “more than double the average rate of the previous decade”. A recent report from the Bruegel think-tank offers a good analysis of this question.

(We should note, though, how impressive a constant 2 per cent a year improvement in energy intensity is, especially coupled with increased carbon efficiency of energy. While not enough, it illustrates why the idea that perennial economic growth is incompatible with planetary boundaries is wrong.)The required changes will need huge investment. In a decade, the amount invested in clean energy must roughly quadruple from current levels to about $4tn in order to reach the net zero path. The announced pledges scenario merely (merely!) doubles it.

Even just to satisfy announced pledges, oil demand has to peak in 2025 then fall. That should give pause to oil-producing nations. If they do not curtail production, they will very soon be fighting to supply a shrinking market. The resistance to phasing out oil production by producing countries may soon prove unsustainable. (It was a big issue in last month’s Norwegian elections, and the new government taking office today resolutely refuses demands to call time on the oil industry.)

There is much more. Try to give the report itself a closer read — it could be one of the best ways for you to get up to speed before the entire world talks about climate at Glasgow next month.

Other readables

Is America experiencing an unofficial general strike, asks Robert Reich. Sarah O’Connor explains why quitting your job is good for the economy.

When Germany introduced a minimum wage a few years ago, many feared it would hurt low-paid workers by killing their jobs. In fact, new economic research documents that their wages went up significantly, with employment unchanged or even increasing. The way this happened was by smaller, low-productivity businesses shutting down and bigger, high-productivity companies absorbing their workers. In my column this week, I argue that partly because the UK government does not appreciate the exact way in which higher wages can boost productivity, we should not be convinced by its new rhetoric that labour shortages are the way to high wages.

David Allen Green brilliantly captures the disheartening absurdity of Brexit minister Lord David Frost’s rhetorical crusade against the EU: “The big negotiation taking place here is not between the United Kingdom and the European Union, but between the David Frost of 2020 and the David Frost of 2021. And, somehow, both are losing.” To keep up with the twists and turns of the latest Northern Ireland stand-off, do sign up to our newsletter Britain after Brexit, formerly know as Brexit Briefing.

Numbers news

What to watch when China releases its latest GDP numbers.

Recommended newsletters for you

Unhedged — Robert Armstrong dissects the most important market trends and discusses how Wall Street’s best minds respond to them. Sign up here

The Lex Newsletter — Catch up with a letter from Lex’s centres around the world each Wednesday, and a review of the week’s best commentary every Friday. Sign up here

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments