World Bank: four steps to equitable education

Simply sign up to the Education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The Covid-19 pandemic is creating unprecedented disruption to education that threatens both current learning and future earnings of millions of children around the world. We urgently need new approaches to support improvements, including debt reductions so that countries can fund the basic schooling required in the years ahead.

Even before the pandemic, there were growing concerns about the widespread extent of “learning poverty” — the inability to read and understand a basic text by the age of 10.

An estimated 53 per cent of children in lower- and middle-income countries lacked these basic skills — and that proportion could increase to 63 per cent after the crisis. Over the long term, the current generation of students stands to lose $10tn in earnings as a result of education they will have missed.

The immediate consequences for education are just as dire. The economic fallout from Covid-19 could push up to 150m more people into extreme poverty by 2021 — from about 689m today — forcing more children to quit classes forever. Escalating poverty, combined with school closures, poses a particular threat to girls.

Initial evidence suggests that dropout rates are increasing, and girls are less likely than boys to return. Urgent action is needed now. Without determined efforts, inequalities in educational outcomes will widen to a breaking point.

Excessive debt burdens and shrinking revenues are forcing developing countries to scale back investments in human capital.

G20 governments have made progress on debt transparency and debt relief. Through its Debt Service Suspension Initiative this year, the G20 has put in place temporary measures to pause debt service and free up fiscal space to meet urgent coronavirus-related needs. But in the absence of more permanent debt relief, the outlook for poverty, and educational progress, remains bleak.

Participation in debt relief efforts is still far from complete. G20 governments need to further encourage all creditors under their jurisdiction, public and private, to act. This includes amending laws that provide excessive protection to creditors and work against debt reduction.

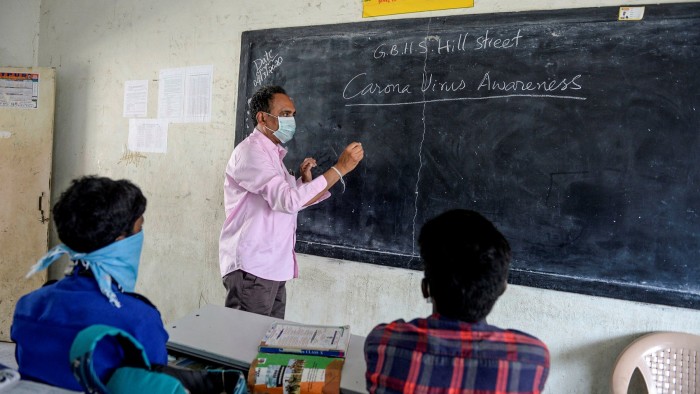

The Covid-19 crisis adds to substantial existing shortcomings in education. But the pandemic offers a chance to accelerate changes that are urgently needed, while ensuring a safe return to school.

The World Bank is working with low- and middle-income countries to accelerate the return to school and to lay the foundations for better, more resilient and more equitable education systems. Our support emphasises four areas:

First, we must bridge the digital divide to allow effective use of online tools for hybrid learning and to reduce large inequities in education systems.

Second, countries need to accelerate their investment in qualified teachers, providing practical training to improve learning and skills.

Third, education must reflect the importance of families and conditions at home, and ensure continuity of learning both in the classroom and in the community.

Finally, it must be embedded in broader policies that invest in and protect young people, including measure to address sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment.

Countries around the world are stepping up to the challenge, deploying new approaches and innovations. Jordan, the Philippines and Turkey are developing new TV and digital content and reaching more children at home.

Rwanda has used radio as well as sign language widely to boost accessibility. Pakistan is providing access to online platforms for more than a million university students, while Brazil is improving internet connectivity and digital education materials.

In Guyana, our focus includes the core skills students need to progress to the next level in their education; teacher training and modification of national assessments to reflect public health needs and lost time.

In all, the World Bank is working in 62 countries, totalling $11.5bn in new and restructured projects covering the entire cycle from early childhood to higher education. So far, these Covid-related efforts are reaching more than 400m students and more than 16m teachers.

Learning outcomes are a foundation for building human capital, the engine that underpins every country’s growth and productivity. Hard-won human capital gains over the past decade — highlighted in our Human Capital Index 2020 Report — are in jeopardy.

This is why during the first 100 days of the pandemic response about half of our total operational commitments — a total of $16.7bn — were for human capital priorities, like education and health.

Greater debt relief, along with enhanced tax collection and better prioritisation and management of public expenditure, will free up resources for developing countries to spend on educating their people and rebuilding their economies.

Smarter, more equitable education systems that are increasingly resilient to shocks like Covid-19 form the building blocks on which children’s success will depend. This is a long-term agenda for learning, but the pandemic has propelled the future to today.

David Malpass is president of the World Bank Group

Comments