‘Design should make people happy’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Martin Brudnizki will be speaking at “The future of design” at the FT Weekend Festival on September 4; ftweekendfestival.com

Creating an interior is such an emotional process,” says Martin Brudnizki, the Swedish designer, who should know more than most. In the 20 years since setting up his London studio, he has masterminded some of the city’s most magical and enduring dining scenes – J Sheekey Oyster Bar, Scott’s, Harry’s Bar, the Ivy, and the deliciously decadent Annabel’s nightclub. His is an unashamedly high-octane vision of hospitality with ever-growing global scope.

The pandemic, and the economic uncertainty that long foreshadowed it, has done little to dent Brudnizki’s output. His New York office, which opened in 2012, continues to expand, and right now he is overseeing a sweep of projects that include a French nightclub for the storied Costes clan, a pair of Paris hotels and Manhattan restaurants, and a fleet of private homes from Lahore to London (including one for his star client, the restaurateur Richard Caring). Despite operating at warp speed, he describes the experience of last year as “difficult, difficult, difficult”. Beyond the logistical headaches, for someone so keenly attuned to the emotive power of design, there’s little joy in sharing decorative schemes over Zoom with clients that you’ve never actually met. “You really need to be in the room with people,” he says. “To feel the fabrics and run your hand over the materials and the marble.”

Amid this newly muted digital reality, Brudnizki has sought solace in the personal. He has just completed work on his own new home, an apartment in a 17th-century house near the Goodwood Estate in West Sussex. A former bolthole of the late Tory PM Anthony Eden, it’s a place where Brudnizki can, he says, live out his own “Arcadian fantasy of English country life”. And this month sees the culmination of another dearly held vision – the launch of his debut collection of furniture and accessories for the home, a 14-piece sartorial survey of his Scandinavian roots. True to Brudnizki’s fabulously precise, fastidious style, it’s been something of a slow burn. “I’ve always wanted to create my own furniture brand,” he explains. “But I knew I had to build the design studio first.”

More than 18 months in the making, the pieces were conceived together with design director Nicholas Jeanes, and are the latest line from And Objects, the furniture and lighting firm they established together in 2015, which has collaborated on designs with Porta Romana, George Smith and Drummonds and produces an ongoing fabric capsule with Christopher Farr. Wholly distinct from the work of his studio, these design partnerships were “a huge learning curve”, admits Brudnizki, who, after moving to London in 1993, where he studied interior design, began his career with Philip Michael Wolfson and David Gill before joining David Collins Studio.

The And Objects duo have dubbed their first home-decor line – which spans tables, sofas, consoles, bookcases, lamps, wall-lights and stools – “the anti-collection”. Rather than designing an armchair with an analogous side table, they sketched the floor plan of an imaginary drawing room (one not dissimilar to Brudnizki’s own sitting room) from which the designs gradually evolved. The original moodboards feature a dizzying array of textures, patterns and tones. “None of the pieces match,” says Brudnizki. “They’re all completely individual, but sit together beautifully – they all harmonise.” Each is named after an English village; the harmony stems from the fact that every one is imbued with the spirit of Swedish Grace, a much-overlooked romantic design movement that emerged in the early 20th century. “It’s an incredibly elegant style that’s infused with the patterns and motifs of Swedish folklore. These designers took the idea of modernism and applied it to neo-classicism.”

Essentially art deco seen through the spare and sublimely crafted lens of the Swedes, the movement was first named by the British journalist Philip Morton Shand (grandfather of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall) in The Architectural Review in 1925. Shand was surveying the Swedish pavilion – a Grecian temple designed by architect Carl Bergsten and filled with what Brudnizki calls “spindly modern furniture and folky patterns” – at the International Exhibition of Modern, Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. Its gilded image was cemented a few years later with a dedicated exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “What’s interesting is that even in Sweden it’s sort of forgotten about,” says Brudnizki of this lost piece of maximalist Scandinavian design history, which has since been eclipsed by functionalism and Ikea flat-packs.

Yet Swedish Grace casts a long and elegant shadow on the Stockholm landscape. The designers at its centre are responsible for the city’s brightest beacons of refinement – public buildings that are considered architectural wonders, or complete works of art (Gesamtkunstwerk). Brudnizki, born to a German mother and a Polish father, grew up in a typically modernist Stockholm apartment filled with the shiny newness of that mode – Josef Frank furnishings and seagrass wallpaper among them – but remembers walking among the grandeur of these neoclassical landmarks as a child. “It’s everything for me,” he says. “It’s part of my DNA. My father is buried in the Woodland Cemetery designed by Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz. It’s the most beautiful place.”

He cites another of Asplund’s achievements, the Stockholm Public Library, with its vast dome and stucco walls, as the starting point for the entire And Objects collection. “It’s out of this world,” he says of the space. “The level of craftsmanship and detailing is absolutely staggering.” In Brudnizki’s hands, these architectural qualities give rise to designs with a grand and classical sense of scale. At times, the presence of Swedish Grace is felt very precisely. The simple geometry of the Marden coffee table, for instance, forged from polished plaster with a cast glass top borrows from details of the Stockholm City Hall – a marvel of marble and mosaic with a fairytale tower and golden hall designed by Ragnar Östberg.

There are little touches of Nordic folklore too. The curved metalwork legs of the Den Mead stool are inspired by a Viking bangle, and the Ovington table lamp, made from cast and poured resin, is topped with a green polished shade reminiscent of the Moomin character Snufkin’s green felt hat – in this case adorned with an elegant antique silver bird. The Murano glass Headbourne wall light, meanwhile, is etched with the face of one of the androgynous mystical creatures that are a frequent presence in Swedish folklore stories.

This of course was fairly new to Brudnizki’s co-creator Nicholas Jeanes, who was introduced to Swedish Grace by the pages of a forensic study authored by Gunnela Ivanov. But more than simply an ode to the movement, the collection is a mind-bogglingly beautiful amalgamation of materials and English crafts. Jeanes compares the process of its creation to a game of conversational ping-pong, in which ideas and Post-It doodles were continuously exchanged, discussed and applied. “It’s been incredibly challenging working with so many processes and materials,” he admits. “First finding the right manufacturers and then actually getting them to collaborate with one another.” It took five different workshops to create the Hambledon bookcase alone. Standing more than 2.1m tall, its oak shelves and columns clad in high-polish green lacquerware were hand-milled in Hampshire and its brass fretwork and finials (including 250 decorative nails each embellished with a heraldic shield) forged at the Dorset foundry of Francis Russell Design. “I’m sure the workshops were cursing us at times,” says Brudnizki.

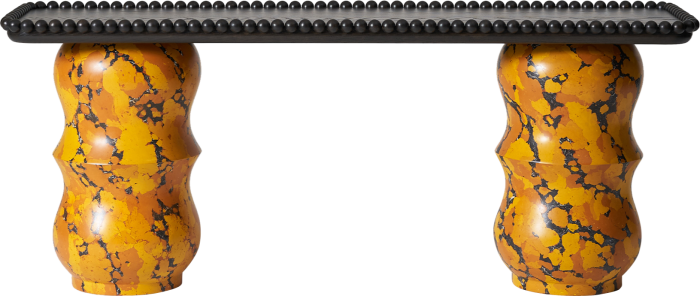

It’s testament to the care and attention that’s been invested in each piece. “Craft is everything,” Brudnizki continues. “Without the skills of these incredible makers, we’re nothing.” Some of the techniques are rather rare. The Bighton side table and Waltham console table are forged from scagliola, a blend of stone and plaster that mimics marble to dramatic effect. Another stroke of genius is the Ropley occasional table. Made entirely from hand-glazed ceramic, its base resembles a jelly mould. Bringing this design to life was far from easy. Jeanes eventually found a building manufacturer in Blackburn, who made the table from clay moulds that were fired and glazed using a delicate technique developed in ancient Egypt called faience. “They’d never made an actual structure before,” Jeanes says.

This is a collection that’s infused not just with beauty but with humour and playfulness. One of the smaller pieces – the Horndean occasional table – takes the form of a pretty pink shell, cast in resin and smashed glass, held together at the base by a brass sea urchin. It’s what Brudnizki calls “a serious piece of fun”. And that’s the point. “I want these designs to make people happy,” he says. This is a designer who believes that such feelgood furniture has the power to impact our state of mind. “It’s about mental health,” says Brudnizki. “There’s nothing nicer than walking into a room that makes you smile. We need to surround ourselves with beauty now more than ever. We can’t just stop living.”

Comments